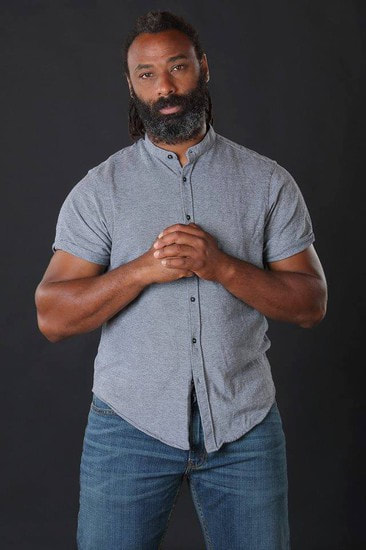

GW: Hey, everyone, this is Guy Windsor, also known as The Sword Guy, and I’m here today with Da’Mon Stith, who is a teacher at silentsword.org specialising in African martial arts. And you can find him at silentsword.org or you can search for him on YouTube at Da’Mon Stith. You can also find him by searching for the Historical African Martial Arts Association. So without further ado, Da’Mon, welcome to the show.

DS: Hey welcome, it’s an honour and a privilege to be here.

GW: Well, thanks for coming along. Now, my first question is usually the same, and that is whereabouts in the world are you?

DS: I am currently living in Austin, Texas, in the United States of America.

GW: Lovely. I’ve actually been to Texas a few times, but I’ve always wanted to go to Austin and never quite made it, and I’m gathering a longer and longer list of friends who live in Austin, including someone I went to school with nearly 40 years ago. So I am past due a visit. Now, you’re best known for your research into African martial arts. So how did that actually get started? Tell us the story.

DS: OK, so this is a long circular story.

GW: We have time.

DS: So the fast version of it and then I’ll get into some of the details. The quick version of it is, I started off as a kid really into martial arts. So I started in traditional Okinawan karate, Shōrin-ryū. And I had the opportunity to train in Okinawa, my father was in the military and he was stationed there for a few years. So I went there and got to train.

GW: Wow, that’s really cool.

DS: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So I while I was there, totally by accident, the gods or fate or whatever, at the same time, I was really into Lord of the Rings. So I remember I went to the library at Kadena Air Force Base and I was looking up books on Lord of the Rings. And I came across this book called The Book of Five Rings. So I thought this sounds interesting. So I got the book and I’m 13 years old and I’m reading Miyamoto Musashi’s Go Rin no Sho. And what really struck me about the book and what he was saying, because I was into martial arts, but he gave me a different perspective on the martial arts, as in incorporating and embodying a number of different skills and attributes that were somewhat related to fighting, but more so related towards the character and the poise of the of the warrior, if you will.

GW: Yeah, mindset.

DS: Yeah, yeah. And that really that really changed the way I saw martial arts. I started seeing it as a form of self-expression. And from that point, the second book that kind of changed me was the Tao of Jeet Kune Do, which really opened my eyes to not only martial arts as a form of self-expression, but it opened up the world of martial arts to me, in that at that time martial arts were considered just to be specialised fighting arts from East Asia, and Jeet Kune Do started to incorporate fighting arts from different parts of the world, so this was the first time I was hearing about Savate or Muay Thai or Kali or Silat. And that really intrigued me that there were other fighting arts around the world that were not East Asian. So I started getting into Jeet Kune Do and particularly the Southeast Asian arts, because at the same time, I’m also developing this curiosity about Africa, African history. And I’m seeing these the Southeast Asian art forms that embody fighting, but they also embody ritual and certain cultural practise.

GW: Yeah, all martial arts are cultural, they’re an expression of the culture from which they come.

DS: Yes indeed. Unfortunately, when you get some of the fighting arts that are a little more common in America, that’s not as apparent, you know. But especially something like Silat or Muay Thai that has music and it has these ritualised stances and positions and postures, it was very, very different than what I was accustomed to. So I got into Southeast Asian martial arts through Jeet Kune Do. And roughly around the same time, I came across Capoeira and Capoeira was really interesting because I really connected to it, the movement and something, even though I didn’t know much about its history or where it came from, most of the practitioners were people of African descent. And it kind of spoke to me in that way. So I started delving into Capoeira, getting deep into it. And I learned that it was a practise that was an extension of older Central African fighting forms. And so I started to see with Capoeira that it wasn’t just a freak accident that this fighting art had developed in Brazil, this chance happening, and actually throughout the African diaspora, there are lots of fighting arts that were that were practised that had a similarity in its form and in its function. And to me, that spoke to me that this is a larger, pretty strong tradition that was being brought over from West and Central Africa, specifically from Central Africa. So Capoeira was my entry into African based fighting arts because once I saw that there were more fighting artists that were related to Capoeira in the Western Atlantic, I started looking for parent arts on the continent.

GW: OK. What did you find?

DS: Well, I found a lot. I found that at least for the arts that were brought to the new world, a lot of them are Congo-based Bantu Arts from Central Africa. I think this is probably best articulated by Professor TJ Desch Obi’s book Fighting for Honor, where during the slave trade, many of the people that were captured and sold as slaves were prisoners of war, and they brought with them these indigenous forms of fighting to the Americas. One interesting thing about the Congolese style of warfare and style of fighting is that their armies didn’t really move in these mass coordinated formations that we kind of envisioned when we’re seeing, like Alexander the Great moving on a battlefield. They were primarily a light infantry, and very few of them carried shields. So what they did is they developed a way of negating and voiding attacks. They would hone their skills through these war dances or these games that they would play. So one war dance was n’senga[09:24], which, according to the Jesuit priest who witnessed this dance, he mentioned that the warriors would do these dances like a military review that consisted of a thousand twists and turns. And they were able to avoid spears and arrows and being hit or cut by swords or whatnot. And then the other practise was N’golo, which is the zebra dance. And these are two of the root arts for Capoeira, in a sense, or are believed to be. It’s kind of the same thing in that it is a practise where the legs are primarily used for kicking and the hands are for support or for an open hand, never really closed fist. But the idea is to develop this idea of corporal dexterity, this ability to use dynamic evasions. And this is exactly what you see in Capoeira, this avoidance of blocking and stopping an attack. And this emphasis on blending, voiding and rolling under over or around these attacks.

GW: I’ve done a bit of sparring with some Capoeira guys. And it’s a really interesting experience. It’s like what you’re doing should not work, and yet somehow I can’t hit you. How do you do that?

DS: Well, going back to the way they fought, part of the reason why they developed these military activities is because again on the battlefield a large part of them weren’t using shields. And so the way that they would arrange themselves on the battlefield would be in these loose skirmishing lines that allowed for personal manoeuvre. And so there was an initial archery phase and then they would close in, in close quarters and they did this in a loose order. So you find a lot of that mentality, that strategy, carry over into the fighting arts in the African diaspora. But moving along the continent, I had to adjust what I was looking for, because you’re kind of looking for African Kung Fu at first. And that’s not what you’re going to find.

GW: What do you find?

DS: Well, what I found… And I say that I found everything. But as far as living traditions go, you’ll find combat sports and physical activities that are used either as a way for training for battle, or if there’s a region where they’re not fighting like that anymore it has a cultural, spiritual…

GW: So it operates in the same sort of space as a folk dance?

DS: Yeah. I think that’s kind of the tendency. What you see is when a fighting art is no longer viable on the battlefield, it either becomes like a sport or some kind of folk practise or some type of game.

GW: We see that in European arts as well. I mean, fencing became a sport. And there are sword dances in various parts of Europe that are clearly related to older forms of swordsmanship that have been converted over the centuries into dances.

DS: Yeah, exactly, exactly. I found that wrestling, of course, is a very universal fighting art throughout the world, especially in Africa. Stick fighting as well was a very common, nearly universal practise on the continent. And the stick was usually a softer training weapon or something more lethal, depending on the culture, whether it’s a sword or if it’s an axe or if it’s a fighting stick that’s either a mace or a club.

GW: I’ve handled some Zulu weapons before. That’s the closest I’ve got to African martial arts. And yeah, I would not want to get over the head with a knobkerrie.

DS: No. I make training weapons and I’ve had a few people commission some. They’re not kerries but they’re based off of M’baku’s staff from Black Panther that are like knobkerries on steroids. So they’re six feet tall. And people are going to use these to spar and I’m like friends don’t hit each other with stuff like this, I’m sorry.

GW: Yeah, we have the same problem with real quarterstaffs. If you’re practising with a quarterstaff, there is no gentle fencing version of it and the same with poleaxes. A blunt poleaxe is called a warhammer. You brought up Black Panther so… A great film, and it’s done wonders for getting the idea of African culture more into the mainstream Marvel universe. Is there any historical basis in any of the martial arts or any of the weapons that we saw in the movie?

DS: Yeah, not so much in the fighting. I don’t really blame them for that, but definitely in the weapons, they use quite a few short swords and knives that were inspired by Central African weapons. Of course, the spear and shield that T’Challa is fighting with is typical Nguni Zulu shield and Iklwa. But the Killmonger’s sword looks like a blend between a Ilwoon-style sword from Central Africa, from the Kuba and Luba people in Central Africa. It looks like a blend between an Ilwoon, with that spatula shaped tip, and there’s another sword I believe is, (Central Africa as far as its weapons is not my strong point,) but I believe it’s the Tetela sword, Tetela knives they have that that that spatula shape or rounded tip into their swords. And it was really reminiscent of that. Other than that, I think the Dora Milaje, their spearheads look like some of the Central African spearheads that I’ve seen. The border tribe, they use the sickle swords that were pretty much like Mambeles.

GW: And now you just mentioned a whole load of weapons that I know absolutely nothing about. So what I’m going to do is when I get this episode transcribed, I will send this section to you. You can correct my spelling for all of these weapons. And then I will find examples of them online and I will stick all of that in the show notes. So listeners who are going, “What the hell did you just say?” can go to the show notes where these words will be spelled out correctly and with pictures where I can find them of the weapons that we’re talking about, which we should help. This is what I was hoping with this interview, is that you would kind of seriously geek out into these areas of martial arts, which is kind of obvious that they must have existed, but I personally know nothing about and I think most people doing historical martial arts, certainly in Europe and the States know nothing about. So we are very, very much on topic. So how do you actually go about recreating these arts? What is what is the process? Because I don’t think you’re working terribly much from written sources.

DS: Right. And that’s the thing. So we approach it in a number of ways. So the first thing is, depending on the region, the region is going to give you certain tools to help with at least understanding its physical culture. So, for example, a good place to start, because we don’t have a lot of written information, especially about like fighting techniques, so we have to use secondary sources. We use living traditions. We’ll use artwork, we’ll use, depending again on a region, sometimes you’ll get an explorer’s account of a battle or duel or fight or weapons being used. So we use that kind of information. We try to construct the weapons and then, especially if it’s a weapon with a very unique design and shape, that shape for us informs us on how it could possibly be used.

GW: It’s pretty much how we approach, for example, for Viking martial arts, where we don’t have much in the way of written records and nothing to actually tell us precisely how the weapons were used. We figure it out from cultural echoes and references in poems and also just getting reproductions of the weapons or handling originals in museums and going, OK, if you were dressed like this and wearing these weapons and I’m dressed like this with these weapons, how would I murder you? And certain things are always true, like leverage and getting hit in the head with a big sword is a really bad plan. So from that, you can figure out something about how things must be have been.

DS: What I have to do for myself is I have to silence the martial artist in me in some in some cases, because there’s two things happening; there’s the innovative martial artist that’s in me, and then there’s the person who’s trying to see what was there without the movement, the martial art, without clouding it. But it helps to already have the ability to wield weapons and to move your body, because in my opinion, it helps me to better digest the information. So I try not to overly insert our martial art eyes. I think very simply and I try to work from a very simple, basic concept of, like you said: you have this, I have that. I’m trying to kill you or wound you and you’re trying to kill me and wound me with my tools and your tools. How can I do that in the simplest way possible? And that’s kind of what gives me control when I’m working through some of this stuff. What’s really crazy and kind of dark (because I cover a couple of regions and one of my regions is ancient Egypt.) So with Egypt, there aren’t any like fight manuals per say in Egypt. There is tons of artwork, and some of it has to be taken with a grain of salt. But some of it is really quite compelling, especially when we’re looking at how well they depicted Egyptian wrestling. One of my current projects now is I’m working on a sourcebook on Egyptian martial arts and combat sports and military traditions. And so I’ve been digesting the wall art at Beni Hasan. Like I tell people, it’s not so much that the Egyptians wrestled any different than the way we wrestle today, what’s freaking amazing is that five thousand years ago, you can see the same wrestling holds that we do today in various styles of wrestling, whether it’s whether it’s folk, whether it’s catch, whether it’s judo, jujitsu. The gypsies were doing some things that were very similar to that back then. And it’s really amazing to see that they were doing this.

GW: And the artwork is often surprisingly reliable, for example, I’m also into woodwork and particularly traditional woodwork, and I’ve seen Egyptian images of tools that I recognise. There’s a glue pot and we know what kind of glue they use because they’ve done analysis on it, And it’s exactly the same as the glue that is being used in Europe 150 years ago. The way they’re using their planes, how the planes are built, those basic designs really haven’t changed since then. In some cases at least, the artwork is really surprisingly reliable.

DS: Yeah. And so, for example, just to build off what you said, the Egyptians, apart from wrestling, stick fighting was one of the most documented combat sports, martial arts, that the Egyptians practised. They practised stick fighting in at least four modalities. They used long sticks, they used stick and a plank style shield. They used single stick and then they used double stick. What’s really amazing is that when you find a living tradition, like the Nuba people in Sudan, who practise, I don’t think they do double stick, but they practise long stick and they practise single stick. And what’s really, really amazing is they practise stick fighting with a plank shield strapped to the arm just like the Egyptians. Most shields in Africa are centre grip shields and the Egyptians used centre grip shields in the New Kingdom. But in the Middle Kingdom, they were using shields that was strapped to the arm. So it’s amazing to see a culture that was from the same area and in contact with the ancient Egyptians, practising quite a few of the same combat sports that the Egyptians did, and this shield and stick, it’s amazing to see that it’s very reminiscent of what you see in the iconography. So in this sweet spot for us, we can see what the artwork depicts and then we can see an echo of it in a living tradition. And we can use that to help us better understand what was there. And, of course, what’s really cool about this process is that I don’t have to be necessarily the master and the reservoir of all wisdom and all knowledge.

GW: A lot of students who want you to be that and you have to educate them into not expecting it.

DS: Yeah, yeah, most definitely. But I like the ability to experiment and be wrong and have to go back to the drawing board and come up with a new theory, or you get some new bit of information that completely throws your whole foundation off whack and you have to readjust. And I think that that is a very humbling position to be in, and I think at least for African martial arts, I think is the best place for us to be in because it’s like the Wild West. There are a lot of gatekeepers and there are a lot of people who are professing to know certain things, and they’re not really practising intellectual honesty. And it really makes it difficult for those of us who are trying to legitimately see what was there. It makes it difficult for us to have credibility.

GW: That was very diplomatically said. I think I know what you’re referring to. If we do what we’re doing properly, it has a lot in common with scientific research where you run experiments. And if the experiment concludes that this hypothesis is wrong, it is a successful experiment. It just didn’t give you the results that you wanted. But if it proves or disproves the hypothesis, the experiment is successful. If it doesn’t give credence to or undermine the hypothesis, then the experiment was useless. So once you have a theory, what you have to do is try and disprove it and if you’re any good at that, you disprove your theories at least as often as you prove them. This is just the process that we have to embrace is we are definitely wrong, but hopefully we are less wrong now than we were last year.

DS: Exactly. That’s a weird place for martial artists to be in, though. Like you said, your students, they have a hard time with that. That’s a hard concept for them.

GW: I have a solution for this. I’ve been teaching these arts for 20 years now. And what I do and I have done for years, maybe a decade by now, is on the first day of the beginner’s course, I introduce them to the book that we’re working from, which is a little bit different for you but the principle is the same. You introduce the students to the idea that this is not your own martial art that you are teaching them because you are the master and it is your art, because what you say goes. You are instead interpreting a martial art that came before and for which you don’t have a living teacher. And so here are the sources. What we’re doing is we are interpreting these sources and trying to make these things work. And then I literally I set them up and I tell them that sometimes we’ll be doing a thing and I say this is how it is in the book and you can have a look at the book and you go, well, hang on, Guy, you’ve got your right foot forward and Fiore has got his left foot forward. So which is it and why? And I try and build in the expectation in the students that they will be rewarded for finding a difference between what I’m saying and what the book says. So if they manage to prove me wrong, good for them. That is good student behaviour, because, of course, a lot of students have been brought up in schools where to prove the teacher wrong is to get kicked out of class and put in detention and bad things happen. Whereas for us, you want students like that who will call you on these things so that you see things that you missed. Sometimes the explanation is, well, OK, yes, I’ve got my right foot forward because we’re not doing that. We are seeing how it changes the play if we do it from the other side, for instance. Or, yes, you’re absolutely right, my bad. Well caught out. Excellent. Carry on. But just building that expectation in from the very beginning means the culture is we’re all doing this research together and we will all get better together. Rather than, Guy’s word is law, and he’s always right. I have been in many martial arts classes where the teacher’s word was law, you don’t argue, disagree or ask questions. You just do as you’re told. And that’s that. It’s very useful when training soldiers because obedience is the first virtue of a soldier. It’s not so useful when you’re training historical martial artists. And I don’t think it’s useful when you’re training duellists either.

DS: Agreed.

GW: Oh, you mentioned you’re writing a book on Egyptian martial arts. Can I get you to promise us publicly that you will come back on the show when it’s ready and tell us all about it?

DS: Yes, I promise. I may be 80 years old when I’m done with it.

GW: That doesn’t matter. Excellent. That sounds like a really, really interesting project and I hope it comes to fruition quickly cause I’m dying to read it.

DS: Can I get dark real fast about Egypt? So I mentioned that there’s no fight books, right. But one other part of our research is battlefield forensics. So the Egyptians didn’t write a manual, but they did write a surgical manual on how to treat battlefield wounds.

GW: Oh, my God, that’s so cool.

DS: No, it’s terrible.

GW: That is so cool. But it’ll tell you how they got the injuries. It’s like CSI. You can tell what kind of weapon it was and what the angle it was coming in at. That is so cool. It may be dark for some people but to me that’s jam, that’s great. OK, now I should mention to the listeners that I first met you at Swordsquatch last year, and actually this podcast interview is the conversation I wanted to have with you then. But it being a public event with loads of people we sort of got started talking about it and then got pulled away to other things. And so it’s nice to be able to get back to that. But I was quite annoyed initially because I was scheduled to teach opposite one of your classes, which I was otherwise hoping to take. But I managed to watch some of the class and having watched the class I was kind of glad I didn’t end up taking it, because I don’t think I would have been able to walk for about a week afterwards because it was very heavy on the legs, which is awesome. So can I ask you something about how you train, what you do for physical conditioning, and what the training in these African arts that you teach looks like.

DS: Got you. All right. A lot of the sword arts that we practise in the western Sahel, in West Africa, (I should say the Sahel is the region between the Sahara and the more tropical regions of West Africa, and it also applies to East Africa.) What you find is like groups like the Tuareg, the Hausa, even to the further east, like the Halun Doa, the Beja, they do sword dances and a lot of their ritualised sparring in a very low crouch position. So a lot of their dances involve this really low centre of gravity and then these explosive jumping, hopping movements. So what I try to do is I try to incorporate either those movements from the dance or movements inspired from the dance as a way of physically conditioning the body. I have a theory that from what I have observed, and I haven’t seen a lot, I’m definitely the blind man touching the elephant’s trunk and telling you what I see, what I think the elephant is, based off of my touch. But from what I’ve experienced, I think that the way that they approach fighting and training for fighting was in a very simple way. So I don’t think that they practise very complicated footwork. From what I’ve seen, the footwork is very simple. You have small incremental adjustments, steps that they make when they’re sparring or they’ll do passing steps taking the rear leg, the rear side forward to get into range. The Tuareg will do an interesting cross step that I’ve noticed in some of their spars. But for the most part, it’s pretty simple. And I think that the way that they physically prepared the body, prepared you to be able to move in a direction that you needed to, was through these very rigorous dances, these sword dances, that involve lots of explosive movement, lots of crouching and then rising really fast. All these things to develop this explosiveness. And I feel like that physical culture was just as much a part of the training than saying, OK, when your opponent steps here, then you step here. So I try to incorporate as much of that kind of stuff and that concept into my training. What I find sometimes, coming from a Capoeira background where we’re constantly moving…

GW: You’re upside down a lot of the time.

DS: Yeah, upside down a lot of the time. What I found is that it’s easy to coast with the sword, you know, I can just sit back and just do my thing.

GW: Yeah, you know, that is actually my preferred way of doing things. I’m very lazy and the whole point of having a sword is it’s a labour-saving device. If I can basically stand still and watch my opponent charge their face onto my point, I’m happy. I don’t want to break a sweat. I just want to kill people.

DS: Yeah, I understand and I respect that.

GW: But to get there you have to get pretty fit and strong whatever and learn all the physical stuff and get physically fit. I totally appreciate that. And any of my students will tell you that we do a fair bit of footwork. As a goal, I think lazy fighting is where I’m at.

DS: But I think we also have work a little harder in certain aspects, because again, a lot of the fighting, even though we have shields that serve as our body armour, there’s still quite a lot of movement of the body behind the shield just because it’s almost like we want to hit. Of course, everyone wants to hit and not be hit. You know what I’m saying? And preferably I tend to follow the defence pyramid of blocking, parry and evasion, interception, that kind of idea. There’s a really interesting sparring drill that we do. What I tell my students is I let them go around where they can parry and they use the sword for defence. And then on the other end of that, I’m like, OK, this next couple of rounds, you guys can’t use your sword to defend. You have to use your movement. And then I punish them for using their sword for defence. I know this sounds terrible when we were just talking about how I’m not the Kung Fu master and I don’t have all the answers. But it’s interesting how they have to approach the fight because there are some questions about to what degree parrying with African swords was a thing. I’m saying according to some European accounts, that that wasn’t a thing. They used primarily the shield for defence.

GW: There are definitely swords are not designed to be particularly effective for parrying. They are purely offensive weapons. I mean, obviously, you parry with them in a pinch, but looking at the damage to swords that we find in museums, we often see that there’s damage consistent with striking, but there’s not much damage consistent with parrying. It’s a cultural thing, I think. It could also be true with metallurgy, how the weapons are built. Not all weapons will actually survive a parry.

DS: And that’s kind of the thing that we have to negotiate when we’re doing this. And I try to cover my bases as far as that goes. So a drill where, yeah, you don’t have your shield and now it’s a matter of hit and don’t be hit. And how do you engage somebody in that kind of match? It is very interesting to see how people move, especially when they know they’re going to be punished. If they get cut, they get killed and punished if they use their sword to protect themselves. Those kind of things are activities that I like to use for training. I use a lot of games to help build certain attributes and certain ideas.

GW: OK, any examples spring to mind?

DS: Well, that was one, and then we do another one, which is the complete opposite of what I had just described, where I’ll have people stand on the wall and one person will attack, the other person will work on parrying and defending with their sword. And gosh, we have flow drills that we do because a lot of our games and our drills come from taking either traditional sparring or traditional games and turning them into drills. So for that example that I just gave you it comes from Matrague, Algerian stick fighting, where the way that Matrague is played is one person attacks, the other person defends and you trade back and forth and the person who’s attacking can do any set number of attacks. And you have to try to catch all those and then you can return the favour. So we would take a practise like that and turn it into a drill where, you know, hey, you’re on your wall, you can’t retreat, you can’t go anywhere. You’re comfortable being behind your stick or behind your blade. And then we could take the same drill and then do it with movement, or the same drill and the idea is, while you’re defending you find a spot, a moment where you can break/disrupt that rhythm with your own attack. I’m trying to think, it’s been such a long time since I’ve actually been in person to teach to anybody, I’m losing all my mojo.

GW: I know the feeling very well. So corona, I imagine, has massively disrupted training and everything in Austin, as it has everywhere else. So how are you keeping yourself fit and active and engaged with your art while the schools are shut?

DS: Well, I’m not keeping myself as fit and active as I should be.

GW: I see. Actually, I’m glad to hear that, because that means maybe the next time I take your class, I will have caught up a little bit in the leg department and I won’t completely die.

DS: Yeah, no, no, no. I need to get back on, I need to get back with it. But we’ve been having virtual classes and that’s been helping. But it’s not quite the same. But it’s what we have, so I’ve been trying to do these little fitness or martial arts based challenges for myself just to kind of keep myself engaged. But, you know, it’s not quite the same.

GW: Yeah, my thing is I’m a teacher first, and if I’m having problems with something, if I just have a student to teach it to, everything gets better. So, you know, I got to the point where I got out of bed and I did my morning training, which that day consisted of literally two squats and one push up and I thought, fuck it, that’ll do for today. Then I thought, this is probably not where I should be. Because I had no seminars, all my seminars were cancelled so there was no particular reason to stay fit, other than pride. So what I did is I organised three mornings a week, Monday, Wednesday and Friday at eight thirty in the morning. I am online with students and it’s just a train along where I do whatever my conditioning training ought to be that day as I feel it. If I’m having a good day it might be quite intense. If I’ve hurt my hip a little bit, it might be a bit more gentle and more focussed on hip mobility or whatever. And the thing is, it’s actually for me because if the students are there, I have to show up. And if the students are there, I can’t just do two squats and a push up and go, fuck it that’ll do for the day. They’re expecting me to be there for forty five minutes. And suddenly I have access to all of this training energy that just didn’t exist before. Because there are students, they’re expecting me. So maybe you might find something about that and maybe get some of your students and get together regularly over Zoom or whatever. And you have to lead them through a conditioning session, so you have to look good. Which means you show no pain. And you might throw up afterwards, but you don’t throw up during.

DS: Yeah. You know, actually that you mentioned that. That has been keeping me grounded. You know, back when I was a younger man, I would do everything that my students were doing. I was definitely charging in the front of the battlefield, like, “Yeah!” That was me in my twenties. As I got into my thirties, I started to take a little easy, I’m saying I started more coaching. Now, in my forties I tend to coach more than I do actually lead from the front. And what the Zoom classes have done for me is now I really can’t coach like that. I can’t coach, I have to go back to demonstrating the majority of what I’m doing, which is really good because I think the hardest thing as an instructor is finding the time for your own personal training. And one easy way to maintain yourself is, like you said, you have people that are there for you, make the most of the time. So I’ve been it’s been good for me in that way that I’ve been able to do that, which has been really cool.

GW: So you’re running Zoom classes at the moment?

DS: I am. I am.

GW: OK, where would people find that?

DS: If anyone is interested, just contact me. I send the link within my group. I should make it more public on Facebook.

GW: So send me a link that people can use and I’ll pop it in the show notes. We’re recording this at the beginning of October. It’s probably going to go out in the middle of December. So we’re quite some way ahead. You’ll know well in advance when the when the show is going out, so if you send whatever is current, then I’ll pop it in the show notes. And anyone who wants to train along with you can get in touch and join in.

DS: Sounds good. Yeah, excellent.

GW: Because getting more people to do your art is always a good thing.

DS: Yeah. I realise how much teaching is very, not to sound new-agey, but very energy based.

GW: Yeah, absolutely. OK, I have a couple of questions that I normally round things off with. And the first of those is what is the best idea that you have not acted on? This is my favourite question.

DS: Oh, man, the best idea that I have not acted on.

GW: Yeah, some people say I am so action oriented, I don’t have any good ideas I have not acted on because as soon as I get a good idea I act on it. And that’s a perfectly good response. But actually, most people I interviewed have something, maybe there’s a book they should have written or a school they should have started.

DS: I like how you say the book. I have a million book ideas, I’ve been writing this historical fantasy novel. It’s got to be two decades now.

GW: It must be pretty good by now.

DS: I don’t know. The world may never know. That is that’s one thing, actually. It’s kind of part of what I’ve been going through these past couple of weeks is I wish that I could manage my time better to maybe have published this book or even the book on the Egyptian martial art. I work at it. I kind of graze and work on it. So I wish that I would have gotten that out last year when I was supposed to.

GW: OK, well I’m quite good at getting books finished and out the door. So if you want any help or advice on that, just drop me a line and I’m happy to advise.

DS: I do actually. Speaking of books, I was meaning to tell you this. When I met you at Squatch, I actually bought one of your books a million years ago, before this was even a thing for me, I should have brought it with me so you could sign it for me.

GW: Was that The Swordsman’s Companion, by any chance?

DS: I can’t remember the title specifically, it was on the longsword.

GW: Yeah, it would almost certainly have been The Swordsman’s Companion, because that’s my first book that came out and it’s proved surprisingly enduring and people really seemed to like it. Actually, let that be an example to you: that book literally changed my life. After that book came out, I started to get contacted by event organisers saying, would you come to our event? Or the reason I have a branch in Singapore is because a couple of guys in Singapore came across that book in a bookshop and then ended up coming to Finland, where I was living at the time, to train for a month, all sorts of things like that. So I would totally recommend getting off your arse and getting your book out the door because you have no idea what it might do for you.

DS: Yeah, you’re right. Point taken.

GW: There’s just a little bit of encouragement for you. All right, so the best idea is you haven’t got your book out. That’s an excellent one. And I’ll be very happy to help you get your book out if you need any advice.

DS: Definitely. I could use as much support as possible.

GW: All right. OK, my last question. Somebody gives you a million dollars to spend improving historical martial arts of whatever kind worldwide. What do you do with the money?

DS: Oh, man. OK. All right. I think definitely the next phase, at least for HAMA, because I think what we have is we have this movement, this martial arts movement that’s going on primarily for us in the West. And then you have the scholars in academia who are studying. Their field of study is something related, maybe not completely the same thing, but something related. Then also, on the other hand, you have these people, these communities, that still practise some of their traditional fighting arts. So what I would like to do is I would like to use that money in order to connect the synopsis between this triangle of interests, between the fight forensic guys like myself, the hardcore academics who are in the field, and then the people that are practising these living traditions. Connect the synopsis between these three groups and make it so that we can travel and work and learn directly from the communities on the continent and then the scholars who have all this brain power going to it. It drives me crazy, it does. I’ll come across an article on military traditions in Ethiopia. And I’m like, oh, yes, there’s going to be something in this, something specific to the swords. But they usually tend to talk about other aspects. No one’s really looking at like the weapons or the gear or that kind of stuff.

GW: It’s more like the logistics of it or the social impact of it or how it was organised culturally. I have the same frustrations myself.

DS: Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Which is great and I give them a thumbs up to that. But you know, to be able to sit with an academic and then to be able to like say OK, well what do you know about this particular weapon, when was it introduced into this region and to be able to have those kind of conversations, to use that money to do that, like going there…

GW: Maybe organising some sort of symposium where you invite practitioners of the living arts and scholars on the theory of various related fields and just getting everybody together into a room to listen to each other’s presentations and talk to each other. That could be really useful, actually.

DS: Yes, indeed.

GW: And can I come?

DS: Yeah, of course, always.

GW: I wouldn’t want to miss that, that would be brilliant.

DS: Yeah. And then on the side of those of the communities, I think it’s really important to invest energy and capital into these communities in that, being from the diaspora and research into the fighting arts of the diaspora, you realise there’s a lot there, but there’s a lot that’s been lost, and so being able to show value for these practises and to offer people a means to make a living and to encourage the development to further these things, that’s invaluable. So, yeah, I would definitely use that money for that reason.

GW: Excellent. Well, thank you. That’s a brilliant idea. All right, I think we are at time. So thank you very much for joining me, Da’Mon. Thank you for a fascinating conversation. And I’m very much looking forward to you coming back on the podcast when you launch your book on Egyptian martial arts. Hint, hint, no pressure.

DS: Yes, sir. Thank you for having me.

GW: Thanks for listening. I hope you enjoyed my conversation with Da’Mon. I certainly did, as you can probably hear. Remember to go along to www.guywindsor.new/podcast for the episode show notes and I’ll be putting pictures of the various weapons that Da’Mon mentioned in those show notes so you can see what they actually look like. And you can also get your free copy of Sword Fighting for Writers, Game Designers and Martial Artists while you are there. A shout out today, of course, to my lovely patrons on Patreon, you can find us there at www.patreon.com/theswordguy and it is particularly helpful to me having the patrons there, not just for the financial support, which is lovely, but also the people I can go to to ask for their preferences about what I do next on the podcast and advice as to who I should perhaps be looking to interview and also specific questions for the various guests. So if that sounds like your cup of tea, by all means, toddle along to www.patreon.com/theswordguy and join us. Tune in next week when I’ll be talking to Maija Soderholm, who is a martial artist, knife designer, and she comes from a very interesting lineage of martial arts and is well known for basically teaching people how to fight with bladed weapons, but without using choreographed drills. So if you want to find out how she does that, tune in next week. Remember to subscribe to this podcast wherever you get your podcasts from, and I will see you there. Cheerio.