GW: I’m here today with Dr Ariella Elema, who is a finder of the forgotten, the hidden and the obscure. She’s an academic and archivist and an armizare practitioner in Toronto. Her Ph.D. thesis, Trial by Battle in France and England, should give you some clue as to why I invited her on the show. But it also won the Canadian Society of Medievalists’ Leonard Boyle dissertation prize, which is very impressive. So without further ado, Ariella, welcome to the show.

AE: Hi. Great to be here, Guy.

GW: It’s nice to meet you. So are you in Toronto at the moment?

AE: Yes, I am.

GW: OK. Actually, Toronto is overrepresented in this broadcast. You are not the only Torontoan, is that the right word?

AE: Torontoan, yeah. Torontonian. Oh, that’s interesting. Who else have you had on here? I haven’t actually looked.

GW: Kimberly Roseblade. She’s been on. Also, Siobhan Richardson. OK. And I’m thinking probably somebody else as well. But if I get the wrong bit of Canada, they might get cross with me, so I’ll shut up at this point.

AE: All right.

GW: OK, so let us know how you got started in historical martial arts, what did that look like?

AE: For me, the historical martial arts actually came out of the history research rather than vice versa, which I think is the case for most people who get into historical martial arts. I was already working on my Ph. and I had started writing the dissertation about trial by combat. And first of all, I needed to get out of the house more because Ph.D. students, when they when they start writing their dissertation, become hermits and just sequester themselves inside tiny, dingy apartments and it’s a little bit sad. And secondly, I was sort of a completist about studying trial by combat, and I thought that if I was writing an entire Ph.D. dissertation on the subject, then obviously I had to learn how to do medieval sword fighting as well.

GW: I wish more academics were like that. It’s like, how can you possibly understand this unless you try it?

AE: Right, exactly. Yeah. Well, I mean…

GW: There are limits to that, of course.

AE: I mean, there’s only so much you can practise beating each other to death. Getting clubbed over the head tends to be a little bit bad for your academic work. But to the extent that we can study it, yes.

GW: OK, so you were doing your thesis and you thought you’d better have a crack at swinging a sword?

AE: Yeah, so at the time, the club but AEMMA, the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts, had a salle in Toronto and I had sort of peripherally heard about them. And at some point they were actually teaching an introductory class through the Royal Ontario Museum, and I signed up for their introductory class back in 2005. And I had a terrific time with a whole lot of crazy people. And from then on, I was hooked. I started coming to AEMMA and I did that for quite a few years.

GW: OK, so are you still training now?

AE: I’m not training at AEMMA anymore, but I do a little bit of armizare on the side.

GW: OK. Who with?

AE: I have some friends in Toronto who are kind of less known in the HEMA community and during the pandemic, I’ve really just been on my own for quite a long time. I have to get back into it. Yes, my friends, if you are out there and you want to do some park training, hit me up. It’s time to get back into it.

GW: Absolutely. And so you’re primarily then as an armizare practitioner, you’re into Fiore. Correct?

AE: Yes. And AEMMA was a little bit ecumenical. I mean, Fiore is the core of their curriculum, not only the longsword, but also the sword in one hand, the grappling and the dagger sections. And at the scholar level, we also did a bit of sword and buckler, and lately they’ve been getting into Bolognese material. But yeah, the core of what I know is Fiore.

GW: OK, well, you’re in good company because I am a Fiorista, through and through. So, OK, before you got into the medieval combat side of things you were studying for your Ph.D. in medieval law, trial by battle, that kind of stuff. What drew you to that?

AE: I think the draw was reading a lot of fantasy novels as a kid and it inspired me to do my undergraduate degree in medieval studies. And then they funded a master’s degree. And so I was like, well, in that case, I’m doing that too. And while I was doing my master’s degree, I was in the University Library one day and I ran into a book. It’s actually a very old book written by Henry Charles Lea in 1866 called Superstition and Force, which has a whole section, a whole sort of sub book, (it’s divided into four books) and one of these books is a history of trial by combat around. And it’s like, wow, this is great. There’s a whole book about this. You can study this as an area of medieval law, and I started looking for more material and there wasn’t a lot of material on trial by combat. There’s one other book about trial by combat in England that was actually written in the 19th century. That’s George Neilson’s book called Trial by Combat. But during the 20th century, for some reason, nobody really wrote a comprehensive history of the subject in English, and slowly I realised that there was this whole little sub field that I could write a Ph.D. about that hardly anybody had studied during the 20th century for some reason. And I had my own little niche. So of course, I had to move into that. That was just too cool to leave alone.

GW: Yeah, fair enough. Why do you think no one studied it in the 20th century?

AE: That’s really a good question. Legal history is a really slow moving field. It’s actually one of the slowest moving academic fields there. Some of these 19th century books like Henry Charles Lea are still referenced fairly frequently. The main textbook Pollock and Maitland’s History of English Law is also from the 19th century. It’s just this slow moving field because I guess it’s very complex and you really have to have practically a whole career in it before you really grasp it well enough to write a massive overview. And I really can’t explain why trial by combat specifically was not studied. I guess partly it’s because I guess there wasn’t like an underlying research question for much of the 20th century. The 20th century was concerned with other topics. The 19th century writers were like “Why were medieval people so irrational and so brutal and so religious?” And I think the 20th century was, I think, not as prejudiced, if you will, against the Middle Ages.

GW: They had been through the Second World War, and the First World War. We were just as prejudiced and brutal.

AE: Exactly well, yeah, people weren’t quite as confident that their own period was somehow more enlightened than the Middle Ages for much of the 20th century. And it’s really from about the mid 70s and the early 80s, people start developing a new research question, which was, “So if medieval people are not irrational when they’re conducting trial by ordeal, what exactly did they think they were doing?” And there was about 30 years of articles kind of tentatively trying to form hypotheses about this and really, by the time I got to my Ph.D., it had just percolated long enough to be a book length work. Some of these ideas.

GW: OK, so your Ph.D. thesis, Trial by Battle in France and England. That’s a very general title.

AE: It’s hugely wide ranging.

GW: I’m one of the few people who actually goes around reading other people’s theses, and I have not read yours, but I’m planning to. So why don’t you tell us what’s in it?

AE: Basically, it is in fact, a general history of trial by combat, trial by battle. From the first records of the practise, which is in the Burgundian law of 502 A.D. until it starts to evolve into the duels of honour. The duels that don’t involve courts of law, which is in the 16th century. So it spans nearly a thousand years. But at the same time, the real heyday of trial by combat was between about 1050 and 1350. That’s when almost all of the case records come from. So in practise it was really more of a three hundred year period.

GW: Oh, just a snap in time. Oh, just three hundred years, that’s fine. Easy peasy.

AE: Right. And also I covered France and England. I was actually originally going to just do England. But first of all, one of my professors suggested that England is sort of over studied in the English speaking world and you need to compare it to other parts of Europe. And secondly, when I started looking at French law, I realised that in England trial by combat was introduced by the Normans in 1066 or shortly thereafter. English law, as it regarded trial by combat was really an extension of Norman law and the customary law of the French speaking continent is sort of one body of law when it comes to trial by combat. It was all of the regions of France had rules about trial by combat that closely resembled each other. So it was good to study France and England together as kind of one unit of French speaking law. Which annoys the heck out of the English.

GW: Exactly. I was just thinking, from this approach, England is basically a province of France.

AE: Yes, yes it is.

GW: As an English person, I’m not sure how I feel about that. OK, so I have a question about what was going on in England before 1066, because in my head and I’ve not studied this in any detail at all. The sort of Anglo-Saxon culture in England, people migrated over from Denmark and places like that, were they not bringing with them things like Holmgangs?

AE: No, and that’s the interesting part, we have a fair bit of legal material from pre-Norman England from Anglo-Saxon, Angles and Saxons in England before the conquest, and while they did adopt trial by ordeal, trials involving carrying hot iron or being dunked in cold water they did not have trial by combat. And there’s some question about when exactly trial by combat arrived in northern Europe amongst the people who settled England in the early Middle Ages. There used to be sort of a misconception that trial by combat was kind of inherently Germanic and that it originated in some misty northern Germanic site. But that doesn’t seem to have been what the records say. If anything, it’s spread out from somewhere in the Burgundian Kingdom in kind of like south-eastern France and all the records kind of kind of move out from there.

GW: OK. Do you think it’s possible that that’s a question of it was a French thing to record them on paper or on vellum or whatever rather than perhaps in other places they just didn’t write it down.

AE: It’s entirely possible because, yeah, that’s kind of where legal writing sort of starts with the Burgundian Kingdom, it starts further south in Italy, but the Ostragoths and originally the Visigoths in Spain don’t seem to have… It doesn’t seem to have been their practise until later either. But the interesting thing about trial by combat in Scandinavia is most of the evidence for it comes from Icelandic sagas, which are later documents recording a period of about the 10th century, but the 10th century is kind of a unique period for Iceland and right around the year 1000, Icelanders themselves actually abolish trial by combat.

GW: So they must have had it.

AE: Yeah, they had it. And it’s recorded in their sagas. But they might not have been really embedded in the culture. It might not have been well embedded when they abandoned it in the year 1000, which is why they abandoned it. You see that several kingdoms of northern Europe, like the Danes, also dropped trial by combat right around that period.

GW: I have so many questions. My first question then, would be if we don’t have evidence of them using trial by combat. Do we have evidence of mortal grievances being settled or mortal questions of law being settled in other ways?

AE: I’m sure we do, and I’m not an expert on Scandinavia. I mean, we do have evidence from the Icelandic sagas that at one point, much of northern Europe did practise Holmgange, but also that that they abandoned it around the year 1000 pretty thoroughly. Which is earlier than much of the rest of Europe.

GW: Because you have to wonder why. I mean, it’s a sword fight. How would you not want to do that?

AE: I’m sure on the larger scale, they still settled large disputes by going to war and having a mass sword fight. But in the case of Iceland, they that’s the point where they establish the Althing, this Icelandic parliament and I think they decided that it was actually more practical to settle disputes by this committee method than having people beat each other to death.

GW: That’s very modern Scandinavian. Let’s do this with a nice democratic system and not have all that nasty violence. It’s very Scandinavian. This is going in interesting directions. So in 1066 or so, the Normans brought some practise of judicial combat over to England. What was judicial combat like in the 11th century in that culture? What was the process?

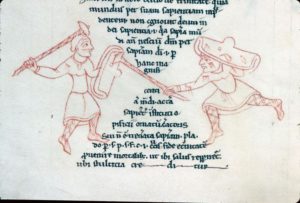

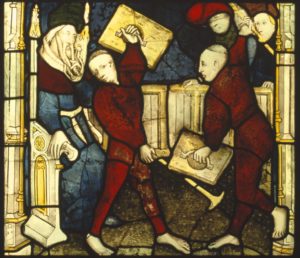

AE: It was kind of fun, from a historian’s point of view, because it was really weird. I think we think of trial by combat as being a sword fight, which was not the case in the majority of cases of trial by combat. First of all, it probably wasn’t a fight at all. Most of the time it worked the way a strike works in modern labour law, you set a date for a big showdown somewhere down the line and then you get the two parties to negotiate and negotiate and negotiate and try to play chicken with each other. And eventually they reach a deal. And the whole point was for the two parties in a dispute to reach a deal before they have a big showdown and fight each other. And if there is a fight, it actually means that somebody made a bit of a political miscalculation or a miscalculation of the opposition. And then the fight itself was rarely with swords, swords and military equipment were for wealthy and aristocratic people having a trial by combat. Your average common person fighting a trial by combat fought it with a wooden club. It was like a fight with baseball bats. And in England, they’re really strangely shaped baseball bats as well, usually they have either a knob on the end or almost like a T square or a pick. None of them have survived, but the images show something that looks like a pick or like a cross piece on the head of the weapon. So it was a much stranger looking fight than we would expect.

GW: Can I just check something? I think in most people’s heads, a trial by combat is two knights having a go at it over some issue of like somebody murdered somebody or somebody raped someone. Some serious crime has been committed and one has accused the other. And so they’re fighting it out to see whether the accuser is correct or whether the defendant is correct.

AE: That’s right.

GW: Yeah, that’s what’s in most people’s heads. But I just got the impression from what you said that actually most trials by combat were not done by the aristocracy. They were more commonly done by the more common people. So this was a judicial process that was accessible by pretty much everyone. Is that true?

AE: Absolutely, yes.

GW: That has completely changed my mental picture of what trial by combat is because I’ve always known that, you know, we’ve got pictures in some of the German fight books of like a man in a hole with a club, I think, and a woman with a rock in a veil and they have to fight each other. And if the man comes out of the hole, he loses. If the woman goes into the hole, she loses. And obviously, if one of them gets clubbed to death, they lose. But we have vastly more pictures of posh people fighting with swords and armour and that sort of thing.

AE: Exactly.

GW: And these pictures of the more common folk trials by combat are much rarer. So I’ve had the impression in my head that most of these fights were done by the aristocracy. But actually, that’s not true. Well I’m very glad I called you.

AE: Yeah, yeah. I think we have better records in a lot of cases of the fights of the aristocracy because they tend to be the ones that the chroniclers write detailed descriptions of. But when you dig into medieval legal records and you get these short little one paragraph summaries of legal cases, there are in fact, vastly more cases of trial by combat between commoners.

GW: Fascinating. And they’re using specialised equipment for that?

AE: Yeah, or in some cases, the wooden club may just have been a big stick. But yes, they’re using in England and Normandy they have these strange horned clubs and in a lot of the German speaking world they have very specialised clothing. Towards the later Middle Ages they’re all kind of sewn up into these tight leather suits.

GW: That’s a very German thing.

AE: They resemble nothing so much as gimp-suits.

GW: Apologies to my German friends.

AE: We have records too from Burgundy, from what’s now northern France, they weren’t just wearing leather suits. Before the fight, they smeared the suits in grease and fat, so that when they grappled, they’d be all greasy and slippery.

GW: Wow. So it’s like medieval, gimp-suited, mud wrestling, basically. That’s just the kind of show this is. OK. So what was the process by which the trial by combat would occur?

AE: So, generally, in very broad terms, in France and England, you have a dispute between two people. It could be a criminal dispute, in which case it’s a very serious crime involving murder or major robbery. Treason. Treason was a big one, especially towards the end of the Middle Ages. But earlier, it could also be a property dispute. Before 1300 a lot of cases were about who owned a piece of land.

GW: Sorry, Lady Agnes Hotot, late 14th century England. Famously, her father was in dispute with his neighbour over a piece of land, and they agreed to joust upon the disputed land, and whoever won the joust won the land. And on the day of the joust, he was taken ill with the gout. And so she went and rode the joust in his stead and knocked the neighbour off his horse. And having defeated him then takes off the helmet and reveals that is actually the daughter, not the father who has knocked him off his horse. The people who tend to follow the show often follow a lot of my other work, and Lady Agnes Hotot is the model for one of the four character decks in my sword fighting card game Audatia.

AE: So oh, that’s terrific. I have not heard that story.

GW: Have you not? Oh, wow, I will gladly send you the reference. Sorry, I interrupted you. So you said earlier on it was about a piece of land.

AE: Yeah, yeah. Property disputes worked a little differently from the criminal ones. But basically the process was in the case of property, I was saying, earlier in the Middle Ages, we just kind of assume nowadays that people who own property that it’s not difficult to prove that you own this piece of property. You produce a written deed and you say, well, I own this piece of property and there’s a registry office somewhere that has recorded that you own this piece of property. But in the Middle Ages, first of all, you might not have a written charter saying that you own a particular piece of property. Somebody might show up and say, well, actually, that belongs to me by inheritance through by my uncle who had no children and died young. But technically this is mine, even though you’ve been farming it all your life. And secondly, the thing you have to remember about medieval law is that live people, particularly the word of honourable men, trumps documents.

GW: Really?

AE: Yes.

GW: Wow. Not anymore.

AE: Yeah. The document is, as far as the medieval people are concerned, up until the late Middle Ages or so, a document is really just words written on the skin of a dead sheep. And compared to the words spoken through the mouth of an honourable man, like dead sheep have no honour. So in order to prove that you own a piece of land the usual method would be to gather together a group of honourable men from the neighbourhood to kind of look into the matter and make a pronouncement on the subject. But sometimes they didn’t know they’re like, I don’t know, he’s been living there for a while. But does he technically own it? We don’t know. And then you have a real problem because medieval rules of evidence don’t have good ways of proving that you own something and you’re going to have to make a deal with the person who said that they own it. And if you can’t make a deal, if you can’t work something out, then you might have to fight him.

GW: OK. And so let’s say it goes to the fight. What is that process like?

AE: It also involved a lot of court days. First, you have to go to court and you have to make your accusation in front of the judge who is probably your lord. And then he has to send someone out to summon the person you’ve accused and set another court date for both of you to show up and for you to make the accusation and for him to deny it. And then you have to pick a method. Trial by combat was never the default method of settling a court case. So it has to be decided that this is not a case that you can settle on with easy evidence or by convening a committee of a jury of people from the countryside. Or it has to be decided that trial by combat is really the only way to settle this messy, complicated dispute. And that might take a couple of different court days, of being summoned and coming back and going back and forth. And then eventually there’s a point where the battle is, in English parlance, the battle is waged, which doesn’t mean that it’s fought, but it means that the people pledged to have a battle at a later date.

GW: So that’s the same route as “wager” as a pledge. So a bet.

AE: Pretty much. Yeah, the same. And it comes from the French word, a gage, it’s a physical object that you give to someone as a pledge that you’re going to do something later. And in the case of trial by battle right from about the year, 1000, traditionally you handed over a glove to somebody as your pledge that you were going to hold a battle later. The glove was almost kind of like a document for the illiterate. Because gloves come in matching pairs and it was like this mnemonic saying, I have this glove and gloves are kind of unique because they’re not mass produced in the Middle Ages, so everybody’s got like a pair of gloves that are uniquely theirs. So if you hand one of your two gloves over to somebody else that’s your pledge kind of like your certificate that you are going to have a duel later, unless you make a deal before the day of the duel.

GW: So is that where the notion of slapping people around the face or throwing down the glove comes from?

AE: Yes, yes it does. And I think people got more dramatic about it later, started hurling it. Well, first it became a tradition to kind of to drop the glove on the floor and have someone pick it up. And then I think by the time you get into extrajudicial duels around the 16th century or so, people start to get really dramatic and slap people about the face. And that’s after the Middle Ages.

GW: Huh? OK, the problem with talking to you, Ariella, is that I completely lose track. This is great. So the glove was being handed over and as a kind of promise that if we don’t get it sorted out, we will have this battle later. And so there must be some kind of legal restrictions as to what is appropriate to be settled by trials by combat?

AE: Right. And those change over the course of the Middle Ages. At first, property disputes, if the property was worth more than a certain amount of money, could be settled by trial by combat. But that has pretty much died out in France and England by about thirteen hundred and the trend was that increasingly trial by combat could only be used for criminal cases and increasingly serious crimes. You never really wanted to use trial by combat for a trivial case because if it was a small dispute it could end up turning into a big dispute as if people start physically maiming and killing each other over it. But increasingly, it becomes trial by combat, mostly about murder and treason.

GW: OK. And so in that case, the outcome would be whoever loses would be then convicted and therefore executed.

AE: That’s right.

GW: OK, so the stakes are pretty damn high.

AE: Yeah. Towards the end, certainly. What you see in some of the earlier trials by combat over property was one of the rules in France and England was that you could have a champion for property disputes, though not for criminal cases. So what you actually saw in some of these property disputes were champions who, if the case actually went all the way to a duel, the champions were sort of incentivised, not to do anything that would be physically dangerous to themselves. There are cases where you hear about guys circling each other for several hours looking for an opening while the principal parties are busily negotiating on the sidelines, trying to reach a settlement and just kind of watching the fight and saying, oh, actually, your guy is looking tired and he might not do well. Maybe you should settle now before you lose everything.

GW: So you can actually settle after the fight had begun?

AE: You could. Yeah, I mean, if it was a property dispute and you weren’t actually fighting yourself.

GW: Huh? OK. And do we have any record of people being trained for these duels?

AE: We do have a few cases. In fact, a fellow in England was probably the very first example of the English attempting something involving Crown Prosecution. And this was a champion who had turned King’s evidence and he was kind of an outlaw. His life had been spared if he would fight duels against several other outlaws. And then they started sending him around England to accuse other people and fight them, even though he probably didn’t know them. Yeah, oh, right, so training, that was the question.

GW: No, that’s OK. The notion of him being like a special prosecutor.

AE: Yeah. There’s a record of somebody being hired as this guy’s trainer who went around with him and kind of escorted him around England. And we think this is not only the first Crown prosecutor in England, but also the first example of a trainer for somebody.

GW: What period is this?

AE: It’s about 1100.

GW: Oh my god. It would be so interesting to find out how they trained.

AE: Yeah, and I’ve looked any kind of example for explaining how they trained. But I haven’t really found much for that period.

GW: So I’m guessing this guy would have been fighting with that strange cudgel-type thing.

AE: Yes.

GW: OK, so he’s not a knight, he’s not going around with a sword, he’s a commoner.

AE: Yeah, in fact, a disreputable commoner at that.

GW: Does that club have a particular technical name in law?

AE: In Latin, they call it a Baculus Cornutus, a horned stick.

GW: Baculus Cornutus, okay. Huh. I know that there are going to be some people listening to this who are going to take a little bit of research and they’re going to start figuring out how to fight with a Baculus Cornutus.

AE: I would like to see it. I hope they put it on YouTube because that would be very interesting because you can use the horns to hook, theoretically.

GW: It’s like a sort of walking stick or a crutch. If anybody listening does that, please send me a link to it or whatever, and I will send it on to Ariella so that you can see it. Baculus Cornutus. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, everyone listening, is to formulate a reasonable system of combat for the Baculus Cornutus. My God, that’s brilliant.

AE: That would be great. Unfortunately, we don’t have any good records for how one of these was constructed. I have looked. Mostly we just have pictures. I can send you a whole lot of pictures and you could guess what exactly it’s made of and how it’s put together.

GW: Please do, and I’ll put them in the show notes so people can find them there. All right. The Last Duel, the movie. Suddenly, everyone is suddenly an expert on medieval law and judicial combat practise suddenly because they’ve heard of a movie about it or even seen the trailer and some of them have even seen the film. OK. I’m not sure it would be very professional me to ask you what you think of the film itself.

AE: I kind of liked it, actually. Not that I’ve seen it. You have to really let your eyes glaze over a little bit and look at the big picture and ignore the goofy details because there are a lot of goofy details.

GW: Yeah, I saw that trailer. I don’t think I would enjoy the film because I don’t like the idea of it always being kind of grainy and grey in medieval times because it’s not true, and the armour was just pissing me off mightily. I couldn’t bear to look at the armour.

AE: I’m afraid you’re just going to have to. Yeah, some people close their eyes for the violence. If you appreciate medieval armour. You’re just going to have to close your eyes for the armour. What can I say?

GW: Ridley Scott needs a slap around the head. OK, so what did you wish everyone watching the film knew about real trials by combat going in?

AE: Mostly that the process was that The Last Duel was a really anomalous duel in so many ways. First of all, it was a rape trial which almost never went to trial by combat. This is one of the only rape trials that were settled by trial by combat. I guess partly because it involves a woman fighting a man which really didn’t happen in the French and English tradition, didn’t really happen in the German tradition, either, actually. They had rules for it, and the rules were deliberately made super weird. You know, this is the whole case of the man standing in the hole and the woman with the rock in the sock. And I think the rules were made super weird to discourage people from actually fighting duels between men and women. And also, I think, to discourage women from bringing cases like that to court at all. And this is something weird about the German fight books is that there are just practically no case records, like legal documents, about a woman fighting a man. There’s exactly one case from Bern in Switzerland in the 13th century, about which we know very little. So the fight books are actually possibly what they’re recording is maybe some fight trainer’s fantasy re-enactment of and what he thinks one of these duels would look like.

GW: Or perhaps somebody asked him the question, we have this obscure, unusual context, how do you think it’ll go?

AE: Yeah, exactly, yeah. And then these fight trainers are showing off their knowledge of obscure practises, I think, in the fight books. So anyway, but on the subject of The Last Duel, first of all, it’s really weird that it’s a rape trial. And secondly, it’s unusual in the history of trial by combat in that it’s a trial by combat between noblemen, though in these very late trials by combat, it was less unusual than it was before because basically only the only trials by combat, nearly the only ones that were going all the way to combat by this point were ones between very privileged people whom the judge kind of couldn’t say no to or didn’t want to say no to and wanted to see the spectacle more than he wanted to resolve the case. And finally, it was unusual in that it went all the way to combat and the combat went all the way to murder and death. That was not necessarily the case in late trials by combat, either. Sometimes the two men are kind of playing chicken with each other. And the judge lets both of them wait right up to the point where they both show up in armour on the day and fight one pass. And if they’re both uninjured at that point, then the judge kind of throws in the baton and says, OK, OK, you’ve both proven that you’re courageous men, and now I am going to impose a settlement on this case. By that point, judges who are usually lords have a little bit more centralised power, and they can start to impose their judgement on a case which was often not the case earlier in the Middle Ages.

GW: Wow. Huh. OK, so maybe the most important thing about the duel that occurred and is sort of shown in The Last Duel movie is that it’s just weird on three counts.

AE: Yeah. And I think possibly the reason why it wasn’t forcibly settled was a). This dispute had had really festered and become a real personal vendetta for the two men. But b). Also, I think from the accounts of the duel, I think part of the problem was that Les Gris probably wounded Carrouges on the first pass quite seriously. And that put the judge in a sticky situation because the judge could not stop the duel and impose a settlement without seeing seeming to be partial to Carrouges because it looked like Carrouges was already losing. And then he managed to reverse it and kill Le Gris. And now I spoiled the movie for you.

GW: Honestly, it happened like 600 years ago, if people have found out the ending by now, that is on them. I don’t believe in spoilers for things that happened. Of course, if the movie had done what Ridley Scott very often does with anything to do with history and just completely made it all up, then that would be different. But if it actually follows what happened, then fair enough, the spoilers are to be expected. When I first saw the trailer and it was called, The Last Duel, I was expecting it to be between Jarnac and Chateigneraie, in 1547 in front of Henry II, from whence the famous “coup de Jarnac” comes. Was that not the last duel, the last formal duel fought before the King?

AE: Well, there’s actually one two years after Jarnac and Chateigneraie that might also qualify as the last duel. It was DaGuerre versus Fendilles. I’m trying to remember what his name was, Claude DaGuerre versus Jacques de Fontaines who was Seigneur de Fendilles. And that was kind of similar. This is the point where the courts have really long stopped ordering judicial duels. But people who have disputes could theoretically talk to the king and get the king to grant them a field in which they could settle their dispute.

GW: OK, so it’s it doesn’t count towards being The Last Duel because it wasn’t it wasn’t imposed by a court.

AE: Yeah, kind of. This is the problem that these are two transitional tools, they’re not the illegal extrajudicial duels of later, but they’re not technically judicial duels. Saying when the last judicial duel in France occurred, means that first you have to define what a judicial duel is. And secondly, you have to define what is France? Because there are also several cases that happened after that, you know, the quote unquote “last duel” that happened in the sovereign duchy of Burgundy.

GW: Well, we would definitely call that France now.

AE: We would call that France now. Yes. And then a couple of other little tiny places that were technically sovereign jurisdictions where a lord could theoretically hold a judicial duel that was not in France.

GW: OK. Yeah, so basically what it is, is The Last Duel is a cool, sexy title. Let’s go with that and let’s not worry too much about the historicity of it.

AE: Kind of, yeah. I mean, you can make an argument for it being the last duel, but it’s not the last duel in France. It’s not the last judicial duel in France. It’s not even the last judicial duel in Paris. It’s not the last judicial duel approved by the King of France. It is the last judicial duel, however, held before the Parliament of Paris, acting as a court of law.

GW: OK. So, not The Last Duel: “The Last Judicial Duel Held Before the Parliament of Paris as a Court of Law”.

AE: Yeah, it’s long as a movie title, I have to admit.

GW: I’m glad we got that sorted out because it was annoying me. Actually, it has more justification for being the last deal than I’d actually originally thought. So that’s good. I’m still going to slap Ridley Scott if I ever see him. But yes, I won’t slap him quite so hard. I think that’s fair. OK, so you’ve obviously immersed yourself in the kind of the world and the culture of trials by combat. So what to your mind are the pros and cons of the practise?

AE: Well, I guess the pros were mostly for the person who is acting as a judge. The pros of a trial by combat are that you can take disputes that medieval judges in the past didn’t really have a lot of power to settle or impose a settlement on. And you can convince these people who might otherwise have a violent feud without asking for your permission. And you can convince them to come into your court and negotiate their settlement in your court, and that gives you more power and prestige as a judge. And it kind of imposes a process and a deadline on that settlement. I think that was the appeal of a trial by combat to medieval people, that you take these very intractable disputes that are really almost impossible to prove given the state of forensic investigations in the Middle Ages and the state of evidence law, which just hadn’t been invented or developed to the state that we think of it today. And it gives people a settlement process. And if they cannot reach any kind of agreement, it gives them a way to roll the dice at the end. And just fight it out.

GW: So you get closure at the end one way or the other. Do you think that it actually had any use as an establishment of truth?

AE: I mean, not in any practical sense, but the thing about medieval people is that is that there are things that they accept that are completely beyond the ability of mortals to figure out. In our society today, we are very uncomfortable with the idea that there are crimes that just can’t be solved. We have entire genres of literature and film devoted to solving the unsolvable crime. But there are some cases that medieval people were just like, the only person who knows the answer to this is God. So we’re going to let God decide this.

GW: I was going to bring up the God question because again, a picture in many people’s heads was that the people who are engaging in this practise, a significant number of them would have simply believed that what we’re basically doing by having a trial by combat is rolling the dice and God will determine the winner. Is that accurate at all?

AE: Yeah, and I guess I’m saying, we’re rolling the dice, but yeah, medieval people would have, it’s complicated because everybody, nearly everybody, in the Middle Ages was a believer and believed that that God might have some role in trial by combat. But actually, from a very early stage in the history of the practise, the theologians were very uncomfortable with the idea that God was actually deciding the winner. There was an argument that from the 9th century onward, where a theologian named Egolbart of Leon said, basically, this is what he called it a temptation of God. You are tempting God to say, are you kidding? I’m not performing a miracle, you know, next Thursday. So you can’t just say to God, hey God, be here next Thursday. Don’t be late. We need a miracle right here. You can’t, as the theologians were saying, you can’t. God doesn’t take orders from you.

GW: Yeah, I can see how that would be theologically difficult to justify.

AE: All right. Many people were also a little bit sceptical that God intervened every single time. They believed that God was capable of intervening in a trial by combat, and it was their justification for holding a trial by combat. But it wasn’t necessarily a reason for holding a trial by combat. That’s my position.

GW: Yeah, which is a lot more nuanced than the story generally put about.

AE: Right.

GW: Which is kind of what we would expect from a specialist, actually. Okay. Tell me you are going to produce a book from your thesis.

AE: Yes. That’s kind of been my pandemic project. I’ve been taking my thesis and turning it into something that people might actually want to read. And also researching some of the German and Italian materials so that I can expand the geographical range and really make it a book about trial by combat in Western Europe generally.

GW: OK. And why don’t we have it yet?

AE: Because I also have to do things that make money.

GW: Oh, I am pretty sure that book could make you a decent whack of cash.

AE: Well, I hope so. It’s still going to be an academic monograph. And but I’m hoping to publish it with an academic publisher who also has a decent distribution system into bookstores. Knock on wood. Yes, if you are an academic publisher and this sounds like a terrific project to you, please be in contact. I’ve been drafting a book proposal, but we’ll see how it goes.

GW: Brilliant, OK. Why an academic publisher?

AE: Mainly because I want the footnotes still in. And I do want the peer review. There are some people who know enough about medieval law that they can improve a book like that.

GW: All right. Presumably, you know those people.

AE: Yeah, sort of.

GW: OK, here’s my thought.

AE: OK.

GW: Academic publishing is a gigantic scam.

AE: Yes. Academic publishing in particular. Yes, I’m aware of that.

GW: So, OK, if your goal with the book is to get a job in academia, partly because that’s on your CV, then you need to have an academic publisher to do it. So if the goal of the book is prestige related, then your plan is good. But if the goal of the book is just to get the word out there and get the ideas into the into the heads of the people who are interested in them and you want to make money doing it. You absolutely do not need an academic publisher. What you want is to publish it yourself.

AE: Yeah, that’s true. Yeah, and if I if I go that route, then I also have to market it myself, which is also a thing that takes time and work and expertise.

GW: But the academic publisher isn’t going to market it for you either. If you want the book to sell, you have to market it yourself no matter what. But things like this podcast are a good way of getting people to talk about your book. So, for example, if your book comes out in say, a year’s time or whatever, you come back on the show and tell everyone about it and that will get you some sales and they will tell their friends and I’ll put it in my newsletter and that will get you some more sales. And then all of your friends who do medieval combat stuff, they’ll all go buy it. And that will generate more sales. The reason I mention this is because I make about half my living from my books.

AE: Oh, no kidding, really? OK, that much.

GW: Really. And I support a wife and two kids on that income.

AE: OK. It’s good to know, thanks.

GW: Yeah, so have a think about your goals. And yeah, if you need the prestige then you need an academic publisher, and you do that knowing that you’re giving up all the money. Because you get the money from the book by getting tenure at the university or something like that, then they pay.

AE: Right, right.

GW: And that’s a perfectly legitimate approach. But if you want to actually make money from the book directly. It is really not hard to publish a book and I mean, pretty much all the stuff that the academic publisher would do things like peer review and layout and editing and that kind of stuff that can all be done independently. I mean, literally.

AE: Right, right. Well, that’s a good point.

GW: I get my stuff peer reviewed. My books have footnotes in where appropriate, I have a professional editor who edits my books and you absolutely will need an editor, of course, because books need editors. Basically, the costs of producing the book are probably around two grand, once you’ve paid everyone. Right, and your publisher, if you have an academic publisher, if they pay you anything at all will pay you maybe four or five.

AE: Right, right, yeah, right.

GW: So they have no real need to sell the book to get their money back. I mean, if they are offering you a 100 hundred grand advance, take it. And that’s brilliant. But they’re not going to offer you a 100 grand advance. When they got that level of skin in the game, then they market the shit out of the book and they put it on the sides of buses and, you know, we become the next Lee Child or whatever. Unlikely with this topic. I’ve been producing my own books for nearly 10 years now, since 2012. They immediately started making me vastly more money.

AE: Oh, really? OK, that’s interesting to note, yeah, because you have kind of the network of people. The HEMA community is particularly easy to reach because they are all in known places.

GW: Exactly. And the HEMA community will be all over this. The phrase that the people who know this stuff use, is the target is not the market. So the target is the people you write the book specifically for that you can really define really clearly. So like for me it is if I produce a another book on Fiore’s longsword. My target is people who want to practise longsword in the style of Fiore dei Liberi. That’s my target. That’s not the market. The market is also pretty much everyone who’s who does longsword actively in any way, in any style. They’re likely to buy it to find out what Fiorists are doing so that they can defeat them.

AE: Right, right. Yeah, exactly.

GW: And then outside of that, you’ve got people who are sort of have a theoretical interest in sword fights like writers, for instance, writing fantasy novels or what have you. And then outside of that, you’ve got people who you could not possibly predict would be interested in your book. For example, I have a friend in New Zealand who is a data scientist and who is all over my medieval longsword book because she thinks it’s a great book for data scientists. I don’t know data science, and I have no idea even what she’s talking about. But there are data scientists who are buying that longsword book for data science reasons I can’t even imagine.

AE: Oh, that’s funny. Yeah. And then partly, I have thought a bit about the market of this book, and I think the HEMA community is part of it, but the market also includes just lawyers who like having a conversation topic. Lawyers are all over this stuff. They love talking about trial by combat. And trying to figure out how to reach networks of lawyers is a little more complicated than figuring out where to reach the HEMA community.

GW: And a significant proportion of the HEMA community are lawyers. I can, for example, put you in touch with two people who practise historical martial arts and are high-level Lawyers, one for the U.S. government and one who’s a patent lawyer with Merchant Gold. Some big company in the states.

AE: Exactly. And what I’m hoping at some point is to get them to review the book for some of their trade publications too that reach even more lawyers.

GW: Exactly. And if you actually get in touch with the trade publications you can do, if you publish yourself and do things like produce an edition of the book, which has that trade publication’s stuff on the back cover.

AE: Oh, interesting, OK.

GW: Yeah. So the rest of the book is identical, so your costs are minimal. You just get the graphic designer to put whatever stuff they want the thing and then you print off, say, a print run of how many they want 300 or whatever, and you sell them those books directly. And 300 books, we’re talking, probably hardback. We’re talking probably forty dollars, a copy of which you’ll keep maybe twenty, if you’re selling directly. So that is 20 times 300 is a $6000 profit.

AE: Yeah, that’s an interesting thought. And I wonder, in the case of lawyers, if they’re more interested in the prestige of the publisher than maybe some other professions.

GW: I would wager not.

AE: You think not?

GW: No, because the vast majority of people have no clue who the publisher of any book is. Literally the only people I can think of who care the slightest bit about a specific publisher are the ones who avoid a particular publisher for political reasons. And the ones who associate a particular publishing house with a particular doing one particular thing well. So, for example, Puffin Books, which is a branch of Penguin that does children’s books and you know, if you buy a Puffin book that it is going to be reasonably well edited. It’s going to be reasonably good, and it’s definitely not going to have anything really nasty in it so you can safely give it to any six year old. But when we’re talking about grown ups, I mean, OK, who published your favourite book?

AE: That’s true, yeah.

GW: I mean, could you even tell me who published Lord of the Rings?

AE: Originally was it Allan and Unwin?

GW: I don’t know.

AE: OK, yeah.

GW: Do you see?

AE: It’s been reprinted by a number of imprints, at this point, the Lord of the Rings. But yeah, that’s a good point.

GW: And the thing is, you have a Ph.D. in the subject, right? That’s your credentials. Not the publishing house. So it’s Dr Ariella whose Ph.D. is on this topic. In the marketing blurb you say, basically has taken her groundbreaking research into this and has… you find a good way to say this in the blurb, but has de-academicised it for a general readership, but keeping all of the details and all of the technical stuff but packaged it so that basically ordinary people can read it without needing a Ph.D. themselves.

AE: Right, right. OK, yeah, that’s actually a good point.

GW: So you are the authority. Honestly, I don’t think anybody cares who published a book unless they are sitting on an admissions or a hiring board in the faculty of a university, then it matters. So that’s just a thought. And obviously, I think this book belongs in people’s libraries, and so if you need any help with any of that process, I’m happy to advise.

AE: Right? OK. Yeah, no, that’s actually a good thought. And I will definitely keep that in mind.

GW: And when it comes out, come back on the show and we can definitely tell everybody about it.

AE: All right. Terrific.

GW: But obviously there is no prestige in self-publishing. But personally, I don’t publish for prestige.

AE: Right, exactly, yeah. And in your case, I think it totally makes sense because I think you know how to reach the HEMA community much better than your average publisher does. Well, much better than even your pretty savvy publisher does.

GW: And if you need to reach the HEMA community better than you’re able to now, you just ask your friend Guy and he’ll do that for you.

AE: All right, terrific.

GW: Because I’ve looked at your stuff and it’s like, this book should be there and people should be able to read it. The thing is, the way I what marketing wise is I send stuff out to, for example, my newsletter if I think I’m doing them a favour. So it’s like if your favourite band came into town and were doing a gig in town and they sent you an email saying, Ariella, we’re going to be in town next week and you can get tickets here. You wouldn’t think, Oh, those scammy bastards trying to sell me their shit, you’d be like, oh thank god, I didn’t miss it. That’s great.

AE: Uh huh. Yes. Right. Yeah.

GW: So when it comes to marketing stuff to my readers, followers, whatever. That’s sort of the am I doing them a favour by telling them to go and buy this thing? When Toby Capwell’s new book on the Armour of the English Knight came out, guys, you’ve got to go buy this book because a). It’s fucking brilliant. B). It is entirely on topic. And C). It’s a limited print run because that’s what these people do with these big, high-end beautiful books. And if you don’t get one while they’re still in stock, they’ll go out of stock and then you’ll have to get one second hand and it’ll be three times as much. So I’m doing them a favour by telling them to go buy the book. And I got people emailing me saying, thank you so much for letting me know. And even people emailing me, with pictures of the book that they’ve bought because they’re so pleased with it. So, you know, for the books like that. And yours is certainly in that kind of area. You can at least sell your books to everyone who buys my books.

AE: Uh. OK, cool. Yeah. Thank you for that advice that that is actually good to think about.

GW: And when you’ve thought about it, let me know if you need any help. I mean it.

AE: All right. Terrific.

GW: Now you mentioned trials by ordeal. The same people, the same culture, that sort of abandoned trials by ordeal, did they replace them with trials by combat?

AE: No. Trials by ordeal were actually abandoned long before or well before trial by combat. It was a process starting in the 12th century, but it really came to a head in 1215, there was something called the Fourth Lateran Council, which was a very large council of bishops who ruled that the church was no longer going to participate in trials by ordeal. These trials, where someone might have to carry a piece of hot iron a certain distance, a trial where someone might be immersed in cold water to see if they floated. But as of 1215 because of these theological questions about whether this was really a judgement of God that the bishops decided that it was no longer admissible for churchmen to participate in trials by ordeal. This had not actually been a practise in church courts. It had been a practise in secular courts. But you still needed a priest to bless the hot iron and make it magic, or bless the water and make it magic, so that it would reject a guilty person and make them float. And without that, the priests to kind of do the woo part, people were like, well, obviously this isn’t a miracle then, and this unilateral ordeals that were dependent on a miracle in order to work started to make no sense and were quickly abandoned. But in the case of a trial by combat, you can still have a combat. And even if God isn’t participating, you come to some kind of a decision at the end of it because it’s a two party type of an ordeal. So it was a little bit different, and I think it also had more support amongst the nobility who were kind of belligerent and liked having the right to be able to fight each other. So trial by combat survived.

GW: OK, so they existed at the same time as each other.

AE: Yes.

GW: OK, so how would you choose one over the other? Let’s say it’s 1150 in England, and there’s the hot iron approach and there’s the trial by combat approach. How do you how do you distinguish between them? How do you choose between them?

AE: Generally, in the case of trial by combat, it meant that both parties in the dispute were considered. They were men and they were honourable men and it was hard to decide between them, but they were both considered people of good reputation. In the case of trial by ordeal, it was always unilateral. It was always only one party in this dispute was going to have to carry the hot iron or be dunked in water, and it was always the party who was a little bit disreputable. And a lot in medieval law depended on what your neighbours thought about you and whether they thought you were actually a person who could make an oath and that oath would be worth something. And if your oath was a little bit questionable, then that might be a reason why you were sent to a unilateral trial by ordeal.

GW: That doesn’t seem very fair, does it?

AE: Well, again, a lot of this has to do with this being a society that doesn’t prove people’s bona fides by documenting things. Nowadays, if you want to prove that you’re an honourable person, you can show people your credit rating and you can show you have evidence of your university degrees, perhaps, or your record of employment. You have you have pieces of paper that you can show people to show them that, that you can do things and you can keep promises. And medieval people had none of that. They had their reputation amongst their neighbours and their reputation amongst their neighbours was hugely important to them because that decided who they could marry and who they could apprentice their children with. And it decided whether they could buy anything on credit. It decided so many things that they needed to do in their daily lives.

GW: Wow, OK. The trial by combat is really there because you have two people who are respected in that community and it’s not like, OK, this person is a known liar and a bit of a thief and nobody likes him. That person is a pillar of the community, so obviously we will say yes, the person we don’t like, they can have a trial by ordeal if they are denying the charge. But we wouldn’t make somebody like that fight somebody so far below them on the social scale.

AE: Right, exactly. Yeah, we wouldn’t make somebody like the respectable person do that.

GW: Fascinating. OK. Wow. All right. I have a lot to think about, and I’ll probably have to have you back at some point to answer my next round of questions. But before we do that, there are lots of questions that I ask most of my guests. And the first is, what is the best idea you’ve never acted on?

AE: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. Usually what I have are really terrible ideas. And then I figure out how to make them work. Like getting a Ph.D. in medieval studies, it’s actually a really terrible idea. It’s financial folly. It really is. I hate to discourage medievalists, but it’s an act of financial folly. But I somehow made it work. And some of my other ideas are kind of crazy, but with a lot of research, they can be made to work too. A couple of summers ago, I went backpacking in the Republic of Georgia and parts of the Republic of Georgia, where people speak no English, mainly Georgian. But I did a truckload of research and actually had a lot of fun going through odd bits of Georgia and learned enough Georgian to speak to taxi drivers who generally don’t speak English in Georgia and get around the country and saw some cool stuff. So I guess what I have are terrible ideas that I kind of hammer into shape until they become fairly good ideas.

GW: That’s a good approach. So what made you pick Georgia?

AE: I’ve slowly been going east in my backpacking adventures and Georgia is this country that’s kind of on the edge of Europe, but it has all kinds of terrific medieval monuments and amazing food and nice weather and gorgeous mountains. But it’s, I think, a little bit less, certainly by Canadians, it’s a little bit less travelled and was just starting to become popular in 2019 before the pandemic hit. So I wanted to go backpacking in somewhere that was kind of medieval, that had a medieval history that was kind of like Europe, but was a little bit offbeat.

GW: Well, I think I think he cracked it with that one. Am I right in thinking that there is a Georgian practise of sword and buckler?

AE: There is, there’s an oral tradition that I think some of the last practitioners passed away in recent years. I tried to get to the heartland of that practise in Khevsureti. And there’s this amazing fortress village called Shatili way up in the mountains, up on the border with Chechnya. But it’s quite difficult to get to Shatili. It’s a dirt road that’s not maintained in the best way through very steep mountains. And I hired a guy with a jeep to get me there, and we got within a few kilometres of Shatili and got to a point where a rock slide or a sort of a dirt slide had washed the entire road into the Argun river. And we were stuck on one side of it, and Shatili was on the other side. And on the far side, there was also a guy with a bulldozer whose bulldozer had broken down, who was looking kind of sad, and we were in the depths of this huge mountain gorge where nobody’s cell phone worked. And so nobody could rescue the guy with the bulldozer. And this was the point where I was really happy I’d hired a guide for that leg because he was like, no, this isn’t going to work. We’re going to have to turn around. And he came up with a Plan B and we went hiking in Khevsureti a little a little further down. But one of these days, I want to get to the fortress village of Shatili, and I think there are some people in Tbilisi who practise Georgian historical martial arts. I have not met up with them, but it would be interesting to talk to them as well.

GW: Yeah, and I have a friend who, I’m not sure if he’s in Seattle, I’ve met him at events in the Seattle area, who has Georgian heritage and showed me a copy of a Georgian sort of manual that describes sword and buckler stuff.

AE: Right. I think there’s a Georgian book or a manual, I’m not sure if it was originally Georgian. There’s also a Russian edition, which might be a translation. I know some of the folks on the American West Coast are looking into to that. And I sort of know a few of them through Facebook, and they’ve been doing some interesting work that I am following.

GW: Yeah, it’s is a part of the world I’ve never been, but you’re definitely selling it to me. I should go to this remote mountain village and I should study sword and buckler with people who can chop my head off.

AE: It’s yeah, it’s great. Terrific food in Georgia and really amazing people. They have this tradition of hospitality to travellers, which is just amazing. And if you can go to Georgia, they’ve been having a rough couple of years.

GW: OK, now my last question. Somebody gives you a million pounds, dollars. The currency doesn’t really matter to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide or, in your case, perhaps knowledge of medieval practises provide. How would you spend the money?

AE: It’s an interesting question. Sadly, a million dollars, even a mere million American or even a million pounds is not going to buy you a training salle in Toronto. Real estate is terrible here.

GW: Well, it’s imaginary money. You can have ten million if you want.

AE: But I think what I would want to do is I would endow some doctoral degrees to get people to look at the interconnectedness of these global traditions of historical martial arts, because I think that the European tradition is now being well studied. But we also have a huge body of manuals in Arabic that I think people should study and start to look at.

GW: They are. Dr Khorasani who’s been on the podcast has done fantastic work in that field.

AE: He’s doing fantastic stuff with Persian manuals. Yes.

GW: There are not an awful lot of people doing that, though, I don’t think.

AE: No, I don’t think so, and if I had a lot of money to endow an institute, I would want to know more about the interconnectedness of these traditions. Because also the Georgian tradition is Georgia was invaded by Persians at one point. Actually more than one point. And I think a lot of these traditions have stuff like interlocking histories that I think it would be really interesting to investigate.

GW: Yeah, whenever you get military powers or cultures fighting each other, there is always an interchange of material and ideas and tactics. Which persisted. Why do we call petrol cans jerry cans? Well, because the British Army ones were a bit rubbish. So whenever they got the chance to nick them off the Germans in the desert, in the Second World War, that’s what they did and the Germans were called Gerry, and so it is a jerry can because the German ones were better than the British one. So they use the German ones with German engineering. So there’s always going to be this taking bits of taking armour and weapons and adapting them, maybe to local things. And whenever you get that kind of conflict, you always have this interchange. It’s not just people murdering each other. There’s this kind of cultural exchange that happens when people fight.

AE: Yes, exactly, and I think we could learn a lot even about the European tradition if we knew more about some of the other traditions. I have a pet theory that I absolutely can’t justify that the really strange tall duelling shields from Talhoffer and some of these German manuals are actually African in origin because you really don’t see a lot of shields like that in the European tradition with a central pole down the back that’s the handhold.

GW: Like a Zulu shield.

AE: Exactly. But you see shields like that pretty much throughout sub-Saharan Africa, and the really odd shape of the Talhoffer shield kind of reminds me of an animal skin stretched the way that some of these African shields are an animal hide stretched over some sticks.

GW: Yeah, my feeling of those duelling shields is that they are basically a raw hide, so an entire hide, that’s been dried in a particular way. Rawhide is pretty tough, but it’s not heavy. Not particularly heavy. So you can make a shield that size. I have friends who’ve made shields like that out of plywood, and you can barely lift the bloody things, fighting with them is really hard work and it doesn’t make a great deal of sense. But yeah, if you make one out of a hide like a cowhide, you get the right size, the right shape and you can swing it around with one hand without too much trouble. Yeah, you see shields like that all over Africa. Good point.

AE: Yeah. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of studies, certainly in English, of the African shields before the colonial period. So I can’t really link up the two traditions, but I just have a pet theory that that somehow the two traditions are linked.

GW: And it’s worth thinking that, the Roman Empire extended into Africa, quite a long way into Africa. And there’s always been this trade around the Mediterranean with African countries and southern European countries and eastern European countries, and Turkey and that lot, trading amongst each other.

AE: Exactly. Yeah, that was something I found when I looked into some of the German material is that German traditions of trial by combat closely follow river watersheds. And there’s a distinctly Upper Rhine, Upper Danube tradition, and there’s a distinctly Middle Rhine tradition with all the rivers that feed into it. If you want to figure out whether a town is in one tradition or another, you find a water map and you can map out quite closely. Because different German regions had different rules for trial by combat. And I kind of suspect that the whole Mediterranean and it’s fed by the Nile and also by the Rhone, and that there were some linkages through the water routes into Europe, the same with the Danube that goes deep into Eastern Europe. And I think some of the strange faceted wooden clubs that you see in the German manuals they resemble these, this faceted mesas that you find in Eastern Europe and points east of that. So anyway, that’s what I’d like to do, I’d like to endow some Ph.D.s in near Middle Eastern studies to go and look at all of these traditions

GW: In today’s market. For a million dollars, you can probably get 100 Ph.D.s because let’s face it, minimum wage is like this distant dream for the average Doctor of Philosophy. Yeah, that was maybe a bit close to the bone. Very true.

AE: Yes. Sadly yes.

GW: Thank you very much for joining me today. It’s been lovely talking to you.

AE: You’re very welcome. That was fun.