GW: Hello, sword people and welcome to The Sword Guy podcast. As this episode is going out on December 24th, may I wish everyone a very Happy Christmas. Of course, we do not take Christmas here. We do not eat or drink or sleep. We simply labour in the dark to produce stuff for your swordy amusement. No, that’s not true at all. Actually, I’m taking pretty much a week off and having a very nice time, thank you very much. So I hope you are also having a jolly good Christmas period. And of course, if you are not a Christmas sort of person, then whatever else you do at this time of year, I hope you’re getting the very best out of it. Now, I should continue with the regular introduction, really, shouldn’t I? This is your host. Dr Guy Windsor, Consulting Swordsmen, teacher and writer. Join me for interviews with historical fencing instructors and experts from a wide range of related disciplines as we discuss swords, history, training and bringing the joy of historical martial arts and Christmas presents into our modern lives. I’m here today with Pamela Muir, who is the founder of the Academy of Chivalric Martial Arts in Arlington, Virginia. She’s been doing historical martial arts since about 2003, and I’ve met her at several events. And may I say she can also tango pretty well. So without further ado, welcome to the show.

PM: Hi, thank you, Guy. Thanks for having me. Glad to be here.

GW: Yeah, it’s nice to see you. So whereabouts are you?

PM: I’m in Arlington, Virginia, which is a suburb of Washington, D.C.

GW: OK. Which is why you have your school in Arlington because you live there. That’s very sensible.

PM: Yeah, yeah. Basically a suburb of Washington, D.C., to give people kind of a more global feel.

GW: Yeah, yeah. I’ve been to Washington, D.C., and I didn’t quite realise when I went to Lord Baltimore’s Challenge. Actually, that’s probably where I saw you last. Did you come and say hello?

PM: I don’t think I went to the Baltimore one.

GW: OK, but the Lord Baltimore’s Challenge was in 2019 and I was there and it turned out that actually we were in Washington, D.C. I hadn’t quite realised they were basically the same place, like they spread out to the point where they are all just kind of merged together in some kind of unholy mélange of cities, it’s very strange. OK, so tell us a bit about how you got started doing historical martial arts.

PM: OK. So I got started, probably the same way most people do. It’s that just the whole romance of it. Who doesn’t want to sword fight? But more specifically in 2003, I was 40 years old at the time, had never done any kind of sports or anything before, but I saw an advertisement for a fencing class and I thought, Oh my gosh, this will be the closest I’ll ever get to learning how to use a real sword is to sign up for sport fencing class. I started, I had a lot of fun with it. Even did one tournament with a whole bunch of really teens, and twenty-somethings.

GW: Children.

PM: But with that, it was a lot of fun, but I was noticing across the room there was this other really cool stuff going on where it’s like they’re not using car antennas. They’re using real swords. Actually, it wasn’t. But you get the point that it’s like that really looked what I wanted to do. Because I always wanted to be Eowyn, you know, fight with a sword and wear the pretty dresses. And so I signed up for the historical fencing class and never looked back. I mean, it spoke to something deep within me. It’s kind of like campfires and something very primaeval. So I studied under Bill Grandy, and he just was amazingly encouraging for this basically un-athletic woman who had never done a sport in her life.

GW: Bill’s been on the show and he’s been a friend of mine for a long time. Yeah, he’s in it for the right reasons. He cares about whether you care about the art and whether you’re into the swords. He doesn’t care about how old you are or how fit you are or anything like that. Because there’s nothing you can do about your age, but you can always get fitter and you can always get stronger and everybody starts somewhere.

PM: Yeah. So I feel like 18 years later, I’m fitter than I was in my thirties. But what also really appealed to me, and so I guess probably the more interesting question is why I stuck with it rather than why I started to begin with. Because everybody wants to pick up a sword, but it’s the fencing language that appeals to me. I have a couple of master’s degrees in mathematics, formal languages and logic. And to me, fencing is a context sensitive language and a fencing bout is a non-deterministic proof. And to me, it’s the language of fencing. One action follows another, and when you get it right, it’s this beautiful, elegant mathematical proof. And I think that’s what really appeals to me is it’s the fencing theory that I engage with, I guess.

GW: That’s fascinating. I honestly didn’t know that you were a mathematician. If I did know, I’d forgotten because my maths is fairly rudimentary.

PM: Well, it’s not something that comes up in casual conversation. I was working on my dissertation when… This is going to sound really corny, but I was working on my dissertation, which was actually context sensitive languages on whether or not they could be deterministic. Anyway, that’s too technically deep. But this is going to sound corny. 9/11 happened, and at the time I had a middle schooler and a kindergartener and I had to decide, where did I want to spend my time? Did I want to spend my time volunteering in their schools, helping in the library, helping kindergarteners learn to read, going on field trips? Or did I want to work on this paper that at the time only about 10 mathematicians in the world were even interested in, they’re like, really, you want to do that? So I kind of gave it up.

GW: OK, well, at least you’re not vulnerable to the sunk costs fallacy.

PM: No.

GW: Which is refreshing because I know lots of people who I have met in universities, for example, who are plugging away at something they don’t really want to be doing or they don’t think is actually important. But they’ve come this far so might as well see it through. And then there are times when that’s not a bad approach, but it’s interesting that you basically give up the PhD for the point of going and teaching in kindergarten, that’s great. As a parent, I think that’s a brilliant decision.

PM: It wasn’t like I was studying how to cure cancer or something like that. I was basically playing with logic symbols.

GW: OK, like when, for example, my youngest was in the neonatal intensive care unit and it was all really horrible and bad. And I was like, why the bloody hell have I spent so much time studying Swordsmanship, when really, I should have been studying paediatrics? Like literally anyone who has not spent their lives studying paediatric medicine is completely useless and have wasted their life completely. And then I thought, well, hang on. We do need engineers and architects to build the hospitals for the paediatric neonatal unit and basically, actually, you know what? It’s not practical to have absolutely everyone being a paediatrician. But yeah, I did sort of think, why on Earth have I spent all this time swinging swords around when I could have been doing something useful? But actually my students tell me that it makes a big difference to their lives that they can study swordsmanship, so well, it is helping somebody.

PM: Yeah, well, even just meeting you at events, you’ve always certainly encouraged me that every time I’ve gone and I’ve taken your classes, I just always get something out of it.

GW: Thank you. OK, so what is a context sensitive language?

PM: OK, so a context sensitive language, just trying to simplify it down. It is what it sounds like. So a formal language is essentially a string of symbols and a context sensitive language, a symbol essentially only has meaning, depending on the symbols around it.

GW: OK, that that makes sense to me as someone who did English at university, not maths. Like a word in English can change its meaning depending on what’s happening before it, what’s happening after it. And so even a sequence of sounds that you would spell it one way if it’s in this context and you would spell it a different way if it’s in that context, it’s actually two completely different words. They just sound the same.

PM: OK. You know, so it’s sort of along those lines. So you’ve probably heard of the concept of a Turing Machine?

GW: Yeah. Like Alan Turing.

PM: Right, so that would be a linear deterministic language is accepted by a Turing machine. You’re just looking at this string of symbols as they are rather than the symbols around them.

GW: OK. All right.

PM: It’s been 20 years since I’ve been working on this.

GW: No, but you said something a little while ago about how a fencing bout is a non-deterministic something or other of a context sensitive language. I was like, hang on, hang on. I’ve never heard fencing described this way. So we’re going to pick this apart and dive in and see where we go. So what is the deterministic aspect of that?

PM: OK, deterministic versus non-deterministic when you’re talking about global languages is to figure out whether the string of symbols is part of the language. A deterministic tree is a single decision tree that you know it’s going to go down. Now it might branch, but at each point in the tree you have only whatever options to go to.

GW: OK.

PM: So, again, just think maybe your binary tree. It might be more than binary, it might be tertiary. But the idea is that there is only a single branch that you can follow that will show that the string of symbols is part of that language. There’s only one branch that will give you the answer, right? A non-deterministic one is that there may be multiple branches, but more than that, you don’t know which branch you’re going to go down when you start. You don’t know specifically which branch will give you the right answer and you don’t know which branch you’re going to start on.

GW: That’s just like fencing.

PM: If you have an infinite amount of computer memory, time, you will eventually come to the right answer, because you can follow this one down and that one down and this one down. But if you don’t, then you’d prefer a language that’s accepted by a deterministic machine. But fencing, I feel, I’m sure is context sensitive, if that makes sense, it is that your action is not independent. It is definitely preceded or followed by your partner’s action. So very content sensitive. At the same time, you have an infinite number of possibilities that are going to lead maybe to the same conclusion, to the same winner. So it’s definitely non-deterministic, that you have no way of knowing at the beginning of the bout if there is a branch that’s going to lead to your desired outcome. And what that branch could possibly be.

GW: Yeah, OK. That makes a lot of sense, and the context sensitive thing, I’m thinking let’s say I’m doing rapier, if I extend my arm and thrust in quarte, for instance, that could be an attack. It could be a feint. It could be a counterattack. It could be a feint in time, to use more modern classical fancy terminology. But there’s lots of different things it could be, which is determined by what you’re doing and when I do that action based on what came right before it. If it’s a riposte, it must have been preceded by a parry. If it is a counterattack it must be done in the time of your attack.

PM: Again, it could be something that you’ve initiated. So not even something that I’ve done, but something that you’re trying to intend to get me to do as well, like a concept of a feint. So there’s no way that it’s even just follow up on what I’ve done. There’s so many things, it’s never an action in isolation. I guess that’s what I’m trying to say.

GW: Yeah, and the action takes its meaning from the things around them, not just the action itself.

PM: Yeah. And when the bout comes down, it doesn’t matter who wins, but when you get a string of actions where just flows really beautifully, it’s a thing of beauty. It really is. It’s just it reminds me again of the satisfaction I would get from doing a mathematical proof, is that look how this flows one thing into the other and who wouldn’t love this, right?

GW: And ideally, you get that definitive end point where the hit is made and it’s clean and you know exactly how it got there. You couldn’t have said five seconds ago whether it would arrive or not. But it feels like it was inevitable after the fact because it was so purely done. Yeah. Huh. I think there’s a book there or at least an article, seriously, on that mathematical language stuff, as applied to – so you see the technical terms there – that mathematical language as applied to fencing theory. OK, so what is that kind of study applied to? Let’s say you’ve finished the dissertation. What would somebody take that information and do with it?

PM: Not much, actually. That’s the problem. It’s a more of a theoretical maths concept than actually applied, it could be related to computer algorithms. But unfortunately, most of it is you’re making the assumption that you have unlimited memory and unlimited time. It’s all theory, it’s just people playing with symbols and it’s a lot of fun. But there is not a lot of practical aspects. On my dissertation proposal, I think I made up a bunch of stuff that said, oh, this could be applied to computer algorithms.

GW: Code breaking is a good one.

PM: Yeah, it was all theory.

GW: OK. Yeah, I’m very much a theorise after the fact sort of person, when I’m studying historical fencing from the source, because usually the fencing theory is not written out in any kind of really explicit way. I mean, in the later systems, it is up to a point, but even so, by looking at the actions that the system includes and seeing what counts as what and how the sequences are supposed to go, you can make all sorts of assumptions about the fencing theory that’s kind of driving that. And I find it much easier to go from practical stuff to theory rather than from theory to practical stuff. So I sort of rationalise the theory after the fact. I’m guessing you prefer to theorise first and then act?

PM: Yeah, but on the other hand, I do go both ways. Some of my favourite bouts that I’ve ever had is where it’s like, it’s really not even bouts, just friendly sparring. We’re not even going to a conclusion, but you have this sequence of actions and then I get hit. And my partner and I both stop and I said that was really cool, let’s go through that again and figure out what happened. So I kind of go back to that’s where the action happened and then I want to go back to the theory, but I never divorce the two.

GW: Sure. So your school says “chivalric” martial arts. And I’m thinking that you’re thinking mostly Liechtenauer. Is that correct?

PM: Yes.

GW: OK. So what to your mind is the underlying theory of chivalric martial arts?

PM: Oh, my word.

GW: Well, just for the listeners…

PM: To every action, there’s an equal but opposite reaction.

GW: No, you can’t have that.

PM: Let’s bring Newton in.

GW: Just to orient the listeners, I do send my guests a list of questions in advance so they can kind of be prepared. That was not on the list. I just threw a curveball at you, to use some kind of sporting metaphor. I don’t even know what sport that comes from. OK. So based on your practise of Liechtenauer fencing, if you if you were going to write out the theory, the underlying tactical structure and theoretical concepts of Liechtenauer, as a theoretician where would you start? That’s probably a fair question. Where would you start?

PM: I really don’t know, I hadn’t thought about it this much, I mean, I can spout stuff that I’ve heard other people say, like the difference between Fiore and Liechtenauer is that Fiore, as far as his pedagogical method is to start with the wrestling and build up from there and Liechtenauer with the longsword…

GW: I would heavily dispute both of those statements.

PM: Yeah, OK. Yeah. And you know, I’m happy with that too. I told you I could parrot things that I’ve heard other people say. So I’m just going to say, this is a really hard question. I’m not sure what you’re getting at.

GW: I’m just curious.

PM: So there’s a difference, I guess, between the mnemonic versus which we don’t get much out of, but that’s the only thing we really have from Liechtenauer as a master. All we have are his glosses and how other people have interpreted it. So I don’t think we can get all that much out of his underlying theory, unless we go back and quote the prologue of it, which I had memorised at one point, about “young man, love the art and women” and whatever it was, but I don’t know specifically what he and his followers would see as the underlying theory. What I would see as the underlying theory is basically it’s all connected. That for every action with the longsword, you could probably go through and find a nearly identical, not necessarily physical because you’re talking about different weapons, but tactic, purpose, response, starting with the longsword, you’re going to find the same thing in the pollax and you’re going to find the same move in dagger, you’re going to find the same move in sword and buckler, you’re going to find the same move in wrestling. And so maybe it’s just that it’s all tied together. It’s all just the same stuff. It’s only the details.

GW: OK, so what assumptions do you think are being made? The way the system is presented, the way the material is presented, you have the Zettel, the mnemonic verses, and you’ve got various techniques with the longsword, various techniques with the wrestling and what have you. Well, first of all, would you say that there is an assumption that your opponent will be moving first, in other words most actions as described are described in a defensive context? Would you say that was true?

PM: No. I just think about the actions of breaking the guard, so to speak, are actions designed to provoke your opponent to move. When you have all these “well this is how you break this guard or that guard” is not a defensive action. It’s designed to, or at least again, in my opinion, to get your opponent to do something.

GW: Yeah, I would agree.

PM: It’s not a defensive action as much other than the fact that you’re not going in there and just attacking, that your provocation still leaves you protected from your opponent’s action.

GW: Yeah. So as you approach your opponent in guard, the thing you’re doing: you either hit them with it or it constrains them to move in a predictable way that you can then exploit. Which is exactly the same thing we do with the rapier, exactly the same thing with sword and buckler, and I would say that’s what Fiore calls “tasting the guards”.

PM: OK.

GW: I should have prepared this better because I’ve gone all excited about like, you’re a mathematician and you do this context sensitive language stuff and non-determinism. Oh, this is so cool. Oh, we can totally apply this to fencing. So what I really want to do is go away for like six months and do some actual research on it. But instead, we’re just going to do a podcast episode. It seems like you have an intellectual framework for looking at units of meaning, symbols or what have you and organising them in particular ways, which when you apply that to historical fencing sources, you’re possibly going to be – I’m putting words in your mouth – perhaps seeing it from a different perspective than someone who doesn’t have that kind of background and training because the actions, like an individual motion on the part of your opponent can be can be written down as a symbol. So you could if you had a symbol for the various actions, symbols, for the various interactions between your opponents, you could basically write down a fencing match as if it was a formula.

PM: Yeah, not only that, but again, you just sparked something in my mind, the same thing is that if you took a fencing match and wrote down the symbol as a formula, then you would have an actual word in your context sensitive language. This is something that actually can happen. But if you could also just write down a string of symbols, but they wouldn’t necessarily be part of that context sensitive language if it couldn’t actually represent a bout.

GW: This reminds me of my card game, which is basically this is what we had to do to produce a card game for to represent Fiore’s Art of Arms or to represent how a sword fight works. That we have to say all the various ways of doing a mandritto fendente, a forehand descending blow and just collapse that down into one thing that is just mandritto fendente on this card. And this card is like this, right? And then the game designer, Samuli Raninen had to basically organise all these possible interactions that could occur in the card game as it was played. And so he would sometimes ring me up saying, Guy, you’re in a left side finestra and your opponent attacks you with a roverso sottano, what can you do? In other words, what is legal? And I’ll say, OK, I would do this. So it strikes me that you can look at this kind of like a game designer would.

PM: Huh. Yeah, I yeah, I think so.

GW: Yeah, there is definitely an article there and I think you should write it. I’ll always do this. My guests come on the show in all good faith and they get set homework. I know. It’s absolutely ridiculous and outrageous. So let me just file away in the back of my head for a bit. And why don’t you tell me about your school and why you founded it and what you specialise in and why?

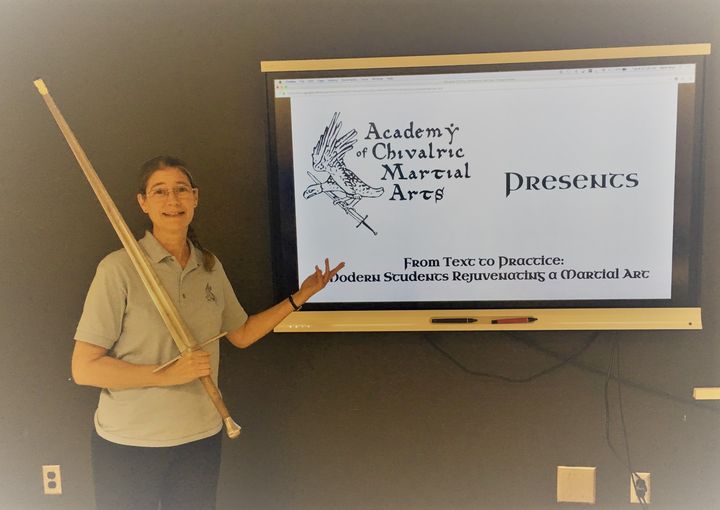

PM: Well, I founded it. My original purpose was basically just to train partners that could hang out in the park with me. There was a local church in my neighbourhood that allowed me to use their basement. You know, I got a few people coming, so mainly I just wanted to train more people to play with me and just being a very highly transient area, it seems like anytime I’ve got somebody that I had a good time playing with, they moved. So that was my original intention of founding it. It’s kind of gone on a different branch since then, where on a whim I submitted a class to our local public schools. It’s called Community Learning. Used to be called Adult Ed. And where as grown ups you can go, you can take guitar or painting. And I’ve taken lots of classes from them, myself, and on their website that says if you have an idea for a class, let us know. So on a whim, I sent them in an outline for a proposal, but basically sort of a lectures / demo course on historical fencing and where it comes from and the fact that this stuff was a real thing that people actually did do this stuff. Anyway, I submitted the outline of the course and the director got it, called me in and said, you’ve got to tell me about this stuff. And he was over the moon, a few months ago he actually sent me, goodness knows how he found it, but it was a YouTube video. I suspect it was from WMAW, where they re-enacted the duel between a man and a woman. Were you there for that event?

GW: I was there for that one.

PM: Yeah. And so he sends me this email and said, did they really do this? Is this really historical? And I’m like, oh yeah. And that’s where I’ve been now putting my energy is in this class where I to present people, show a couple of movie clips, especially The Princess Bride one, the clifftop scene. And I will spring into that from like, OK, where Inigo Montoya was doing all this name dropping? Guess what? These were real people. And then from there, then I go into the medieval and show them pretty pictures from the medieval manuscripts. Talk about how we try and take the text and the picture and translate it into an actual action. I usually bring my husband with me to be my dummy because when I asked the head of Community Learning, can I demonstrate this on students? He said, absolutely not. So I’ll have the slide up on the projector of here’s the medieval manuscript. Here’s what the text says. Here’s how we’re currently interpreting it, and I’ll bring in a bunch my practise equipment showing them how we use, they’re not antique swords, but built like they were to handle they were. I bring in a lot of my library works. I love the fact that there’s so many reproductions and transcripts that are out there now. So I can say this is what a medieval manuscript looked like and let them thumb through it and watch their eyes get really big. And they are always like, will you take a picture of me holding the sword? This is where I’ve gone. This is really where I’ve been putting my energy in lately. It’s just kind of introducing this to people that might not necessarily go out and practise it, but just be a little bit more aware and come away right on. Gee, that was that was really, really cool. Let me tell a friend.

GW: Yeah, and a lot of people don’t know this stuff exists, but as soon as they hear about it, they are so glad it exists. Many of those actually start practising one form or another. So that’s really important. I’m guessing also most of the time when they get suggestions for courses is, please could we have a course on this? In other words, go find an instructor. Whereas you’re saying, well, we could have a course on this, by the way, here’s a course plan and I’ll teach it for you. That’s a much, much, much easier sell than, would you please find me a charango teacher?

PM: Yeah. And he’s also tried to package it, so they put out a little booklet each semester of courses that that are being offered, and he’s tried to package it with another class on medieval architecture.

GW: Oh great. Yeah.

PM: And so it’s kind of, oh, look, these are all kind of listed together to try and try and get some crossover for us as instructors.

GW: Excellent.

PM: I don’t think there’s other people doing this, especially not in this area. I think I’m the only one that’s doing this is almost a history class as opposed to let’s go out and hit each other, which is fine.

GW: Yeah, you may be right. I don’t know of anybody else who is teaching like a night school class on historical fencing as a concept. That’s really interesting. OK, so why take particularly chivalric martial arts? What draws you to those?

PM: Well, I’m a very idealistic person and just the whole concept of chivalry, I went through a whole bunch of ideas in my head about what I wanted to call my school, and I just felt like the idea of putting in chivalric in there emphasised the fact that I wasn’t trying to do something where it’s like, hey, let’s go out and win every tournament there is. To me the idea of chivalry is a lot of respect. Somehow in there, I just think even just the idea of education, being aware of things in other people and that there’s just a lot to unpack in the single word. It was more on what my focus was, which again, my original focus was just to find people to play with, and so I wanted to only attract people that liked the idea of chivalry, because if I’m asking strangers to come and play with me, I want them to have at least a similar mindset to me.

GW: Because what I read from it is Chivalric Martial Arts as opposed to the un-knightly ones. So, for example, Fiore would be chivalric, but 1.33 sword and buckler is not a chivalric martial art. I wouldn’t call any of the rapier systems chivalric.

PM: I guess I was trying to get medieval in there. But yeah, certainly 1.33 not being a knightly art that’s not knights depicted, but on the other hand, I feel that at least in the modern usage of the word chivalry, the fact that, hey, it’s a priest and a scholar together, so I think I’m using chivalry more in the modern sense, OK, I’m kind of fudging my history a little bit because I mean, we could really go into that chivalry in the medieval times is not what we think of as chivalry now.

GW: I’ve had Eleanor Janega on the show, and if I recall rightly, there’s a little bit about how chivalry doesn’t mean what we think it means anymore.

PM: Yeah. So I guess the chivalric is in the modern sense.

GW: OK, so what systems do you actually practise?

PM: So mostly Liechtenauer, but dabble a little bit in 1.33. A little bit of Lecküchner, I guess, could debate on whether that’s Liechtenauer or not.

GW: That’s a really interesting question. And I think again, we could get into some very geeky territory, which I think the listeners actually really like. So OK, in your opinion?

PM: Well, I’m not sure I’m prepared to talk to that.

GW: I am. I tell you what, I will make a few assertions and you can tell me whether you agree with them in principle or not. Is that is a fairer question? OK. All right. I would say that most of the stuff we see in the actual Liechtenauer and longsword material is, if you like, the advanced course, it leaves out a lot of the really basic stuff like parrying and striking.

PM: OK, well, sort of, because I mean, strikes you still have. I mean, it doesn’t give you like super deep instructions on how to do an Oberhau or an Unterhau, but certainly you’ve got the master strikes, I guess, yeah, you’re leaving off the basics. All right. I’ll buy it.

GW: OK, then I would say that the basic fencing, the kind of the common fencing, the standard fencing, the fencing 101, if you like, was probably in the 15th century Germany, it’s not even Germany back then, but you know what I mean, was probably taught through use of the Messer.

PM: I don’t know my history well enough to agree or disagree.

GW: OK, let me say why I think that.

PM: So who are you saying is learning this fencing 101? That’s my question, because I was going to say if it’s just your guy on the street who is going to be hired to protect the king versus somebody from a noble house, for instance.

GW: True.

PM: So I would probably buy it depending on who’s doing the learning 101.

GW: OK. There is a beautiful image which I first came across in Mike Loades’ book. I will put it in the show notes. I’ve interviewed Mike Loades on the show. We talked about the book quite a bit, but there’s this fantastic image of the Emperor Maximilian being given a fencing lesson. There he is crossed longswords with his training partner, with the fencing master standing there basically instructing them, and on the floor in front of them is a pair of Messers and steel gauntlets. And on the floor behind them is a pair of quarterstaffs. And the way I read that image is we begin the Messer, and we then progress through the longsword and then we go to the quarterstaff. And if you look at literally every Messer source I’ve ever come across, it includes things like waiting in a low guard on the left and when the strike comes in, you beat it out of the way and you hit somebody, which is there at the end of Cappoferro where he says it’s a secure way to defend against any sort of blow. It is there at the beginning of Fiore’s longsword material, it is there the beginning of 1.33 where you’re chambered low on the left when the sword comes in from above. So it’s like there are these really fundamental, very common actions which you don’t see in the Liechtenauer longsword of material, but you do see it in all of the Messer sources or pretty much all of the Messer sources. Which gives me the impression that the Messer is the place you go to learn the basics, and yes, you can stick with that weapon and do really advanced fancy stuff with it, as we see in Lecküchner. But pretty much everything that’s in Lecküchner is also in Liechtenauer. You’ve got your equivalents of your Zwerchhaus and your Krumphaus and all of those things, they’re all in there. So my subjective image of how fencing was approached in the 15th century in Germany is you start with the Messer. You go on to the longsword and then maybe do quarterstaff, if that’s where you want to go. And of course, the longsword is the kind of the cool, sexy one. But the Messer is something that everybody has and Maximillian’s Messer actually survives. So even the emperor was using Messers. So it’s not just common people, but the common people have them too. So that’s like the universal sidearm. And then the longsword is sort of like this specialised stuff.

PM: Where would wrestling fit in with that?

GW: I would say that wrestling is one of those fundamental practises that everyone was doing. And you probably learn wrestling before you even touched the Messer. Because I mean, that’s what you teach kids. These days if someone has a five year old who really wants to get into martial arts, I say take them to judo because they’re very unlikely to get hurt. They’re very likely to learn lots of very useful skills, which later on can be adapted into things like, well, are there other wrestling styles, other unarmed styles and what have you. And you are just much less likely to get badly injured than if you’re punching and kicking, or whacking people with sticks, I mean, that’s really dangerous.

PM: Yeah, exactly. Metal sticks.

GW: Would you say that was a reasonable proposition?

PM: Yeah, that’s certainly reasonable. I really hadn’t thought about it before. I have, going back to the maths thing, it’s like when I do this lecture course I explain that with these manuscripts, but what it is, we have the calculus manuscript here. We don’t know how they taught the basic arithmetic.

GW: Yeah, exactly, exactly. And we mentioned my card game. There’s an expansion pack that you can get. Fiore is that the basic style of the game, but that’s an expansion pack you can get, which gives your character Liechtenauer.

PM: OK.

GW: Just because to my mind, looking at it from the perspective of the game. The Liechtenauer system is, yeah, it’s the expansion pack. It’s the extra stuff. It’s the advanced course, if you like. So how do you teach the fundamentals of longsword?

PM: Well, just as far as like, I assume you’re meaning stepping outside of this lecture course. I start with OK footwork. First of all, footwork. How do you stand? How do you hold your body? How do you move through space and do a lot of games just with that alone, how do you move your body physically through space? Being able to move quickly, smoothly with the stance. Imagine you’re top heavy with armour on. I tell you, it’s like what’s easier to knock over, a hat rack or a coffee table? And it’s like be the coffee table. Don’t be the hat rack. So footwork is definitely the start. Then, of course, then with that, how do you stand? How do you hold your body? It’s from there moving in to the guards. And here’s how you hold your body. But then with the guards, I kind of teach them both together with the master strikes. So if your opponent’s in this guard, you might want to do this. That’s where I start and then from there on, it’s kind of non-deterministic like I’ll be thumbing through one of my books and go, oh, that’s what I’m going to do today.

GW: OK, now if you’re thinking of the Liechtenauer stuff as the advanced course, it begs the question, what’s the basic?

PM: I don’t think we know.

GW: What’s his name, Captain America? Jake Norwood. Who’s again been on the show and when I was interviewing him he said that what he’s currently really trying, really interested in, what he’s trying to find out is what actually was this common fencing that everyone is talking about, but no one’s actually describing in the medieval sources. No one wrote a book saying, oh, this is the common fencing, because who the hell would buy a book like that, in period? Everyone wants the advanced course.

PM: Books were expensive, you weren’t going to write a book on common fencing for the common person to buy because they couldn’t buy it.

GW: Exactly. This question is something I ask most of my guests and I have an idea of what your answer might be, but what is the best idea you haven’t acted on?

PM: OK, so haven’t acted on versus kind of sort of acted on, but didn’t follow through, is taking this class that I do for the Adult Ed and doing it in the schools.

GW: Oh, I like that.

PM: And so in the school that I work at currently, I’m a substitute teacher by day. That for one of the world history teachers I was substituting for him and on my little sub notes, I put there when you get to the medieval section I would love to do this class for you guys, if you’re interested, and I never heard anything and I just didn’t have the guts to follow through, but I thought it was a really good idea that I just haven’t followed through on it.

GW: It is a brilliant idea because what is more likely to get kids into history than swords? I mean, really? Yeah, OK. There will be some kids for whom I know steam engines is better and other kids for whom maybe it’s the horses. But I think swords are a pretty sure hook. So how would you expand it into schools because there’s only one of you?

PM: Well, it would just be me going in and recruiting the teacher to be my practise dummy. Because again, you can’t always trust seventh graders once you put a sword in their hand.

GW: That’s very true, although in my experience, I’ve done some stuff and in schools, and you can’t always trust the teachers either.

PM: This is also true. I also think what would be nice about that, too, though, is for the women and non-gendered students to see that, hey, you know, you don’t have to be a boy to be interested in swords.

GW: Or maths.

PM: Yes, well, see, that’s just it. I been in a male dominated field for my whole life. So when I can influence other non-male people to do this kind of thing it’s very emotionally satisfying.

GW: It’s the primary reason why I started the podcast. Because we have a problem in historical martial arts of basically, not enough women are aware that this is something they can actually do. Because most of the people I know who have said I have no idea this was even possible and now I’m doing it. Most of those are women. And the thing is, I’m a bloke, so what can I actually really meaningfully do? And so I can create a podcast with an interview format and have at least half of the guests be women, so it’s really obvious to everyone who comes across the podcast that you don’t have to be a boy to do this. It just struck me as a practical first step. I’ve got no data as to whether it’s doing any good or not, or whether it’s actually working as a get women into the art outreach programme at all. But you know, it’s one of those things where even if it fails in its intended purpose, it’s still a worthwhile thing to do. And so I don’t actually expect it to be a particularly significant step in that direction, but it’s still a step.

PM: Not even just encouraging people to start it, but you’re by doing that, you’re encouraging people to stick with it, so to speak, because most of the faces of the historical martial arts community are men.

GW: Exactly.

PM: You know, I get comments all the time about, well, there should be more women instructors or whatever. At one point, I tried to lobby to be an instructor at an event and just got brushed off.

GW: Really? That’s not good. Well, that’s what happens all the time. It’s like events are doing really, really well when they have like, I don’t know, one in five of the instructors there are women, and most often those women are not teaching a practical class, very often they’re giving a lecture.

PM: Um. I’d say there’s certainly exceptions to that.

GW: Oh, absolutely, yeah. I mean, there are there are many examples of women teaching practical classes, but when we look at the line-up and you look at what they’re actually being asked to teach, the people who are most likely to be given the gym or the wrestling room or whatever, very often it’s the boys, because that’s what boys do.

PM: That’s because they outnumber us.

GW: Except in the general population. And there are there are historical fencing clubs that have like 50 percent or better female membership and my club in Helskinki when I was running it, we usually go about thirty five percent women, but one thing that I noticed a long time ago is that they were tending to get to a certain level and then they would quit, and I had absolutely no idea why. So I got the senior students together and I said, OK, so why were the women quitting? And one of the senior students said, “Guy look around the room.” And it was all blokes. And I said, OK, so what do you do about that? And it’s actually one of my students who suggested that wherever possible, demonstrate with a female student. Because when you take a student in the class to demonstrate with them, you’re basically raising them above the rest of the class. You are putting them on the spot as it were, but also any martial artist knows that is a complement being paid you in public by the instructors. And so I was like oh, OK, well, I’ve been prioritising the technical precision or whatever of the demonstration, rather than its overall effect on the students and after about a year of doing that pretty consistently, we had more senior students who were women. These things can work out at least up to a point. I think that by itself isn’t going to do it. Likewise, the podcast by itself isn’t going to do it. But if there are lots and lots and lots of little things all happening, that might add up together into a really meaningful change. What do you think?

PM: I learn so much from middle schoolers and right now, there’s so much awareness amongst them about gender equity and so on, and at that age, they’re still very idealistic. I would like to encourage them to, hey, you know, you’re interested in this, then go for it. Go do it right out.

GW: Yeah, and I guess the thing is, if they’re given a broad enough perspective then even if the club closest to them that happens to be run by a bunch of burly blokes who aren’t very nice, as may be the case. They won’t assume that that’s all of swords. And maybe they will go looking a bit further afield or start their own club or something like that. I am vividly reminded of an event we were both at, I shan’t say the name, where there was club leaders get together beforehand and the issue of how do we get more women doing this and basically female representation. And there were, as I recall, I think two women there, and as I recall, you were one of them, and as I recall, nobody actually asked you your opinion.

PM: Not only did they not ask me but I would get cut off.

GW: Right, exactly.

PM: Yeah, yeah. but it was more of an attitude like, well, because at the time I didn’t even have my Academy of Chivalric Martial Arts. It’s like, well, you’re not running a school. I was teaching under someone else but not running the school. So you can’t possibly be talking to this topic. Yeah.

GW: Yeah, yeah. Honestly, I think it was done in good faith.

PM: I do too. Their defence was but you’re not actually running a school.

GW: So yeah, it reminds me of the time I was reading Caroline Criado Perez’s book, Invisible Women. Have you come across it?

PM: No.

GW: Oh, it’s a fantastic book. She’s a data scientist as she goes through, basically many, many examples of things that have been done horribly badly because the data that these things were based on was not disaggregated by sex. In other words, for instance, cars which get a five star safety rating with a male standard crash test dummy, get maybe a three star when you have a female model dummy. Right? And yet women are driving these cars, and sure enough, more women are getting killed and injured in car crashes than men because the cars are designed to be safe for men. Drugs in medicine, which are tested on male subjects, even drugs which are only ever going to be taken by women, are tested on male only subjects because men have more kind of stable hormone levels and what have you, it’s just easier to get clean data off them. But the drug is not supposed to work on them. It drives me absolutely… I mean, I was reading that book in New Zealand at the time, and it was driving me absolutely up the wall and I was about halfway through it. It was at this event, I was sitting around after dinner and everyone’s chatting. A friend of mine called Agate, who’s a data scientist, a data scientist, that’s the first thing, and a woman, and had actually read the whole book. When I brought up the subject of this book that it was getting me so cross she was like, yeah, I’ve read it and she started talking about it. One of the male students there, basically politely and well, didn’t mean anything by it, shushed her so that Guy could talk about the book that he wasn’t qualified to actually comment on because not a data scientist and not a woman, and also hadn’t read the whole of yet. It’s like, argh! If you ever wanted a perfect example of why that book matters, it’s that. And here I am. I got you on my show to talk. And that’s me, rabbit rabbit rabbit.

PM: Yeah, but you know what? I’m actually just enjoying the chance to chat to you. I feel like we’ve had a pretty deep conversation that this is usually the kind of conversation I only get into after hours at an event after a couple of ciders.

GW: Yeah, it’s a little early in the morning for the ciders.

PM: I’ll be getting out the plastic knives in a minute.

GW: Exactly. OK, so my last question then. Somebody gives you a million dollars to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide. How would you spend the money?

PM: On scholarships to get people to go to events. I think learning in person from people like you, people like Christian Tobler, Bill Grandy. People that have just been out there and studying this for 20 some years and the internet’s been wonderful. I think it actually kind of sparked the getting more and more people into the historical martial arts because we could now communicate with each other. But on the other hand, it’s allowed people to live in their own little insulated bubbles, just like you get in modern politics with the “oh I did my research” is that you see all this stuff where people going well, I’ve been studying this for three years and I’m watching them get into arguments with people who’ve been doing it for 20. And I think this wouldn’t take place as much if we could get people face to face to talk about things, demonstrate the techniques, talk about in person. Well, let’s freeze frame right here. See where we’re both at, see how this works, and you can’t do that on the internet. So for me personally, based on my journey on historical martial arts, going to events was what made me the martial artist that I am, that I’m not just staying in my own little bubble and learning things just the people nearby me are learning. But I got to dabble a little bit in Fiore by going and taking a class from somebody else. And I think if we could get people together to talk about things, to demonstrate things, to share knowledge, and it might be those, hey, this person has been doing it for only three years, did have a light bulb moment that the rest of us need to know about. But the only way of knowing that is that this is a physical art and to just sit here and type at each other, even people posting videos more and more, which I think is awesome, but that’s still really hard. Video doesn’t really show even a complete picture.

GW: This is why firstly, I don’t do Facebook any more. And secondly, I don’t release videos out of context anymore. I do tons and tons of videos, I put out probably 100 videos in the last year. But they’re all put up with a private link and then they are linked, for example, within a blog post or to an email to my email list or to like a book I wrote recently, Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice, it’s Fiore’s longsword plays and you’ve got my transcription – this is why I think he’s actually saying in Italian; my translation – this is what I think he’s saying in English; then my explanation – this is how I think you actually do it. And then there’s a video clip. So that video clip is not just here’s what I think how the sword thing does, right? It’s, OK, from this transcription of this translation and this interpretation, this is how I think it looks in practise. So it’s part of that much larger context. And if you just dump them out without all of that context, it’s a lot better than nothing, but it’s not a really good way of disseminating the depth of the art, I don’t think, or certainly not for argument. Yeah, having a good faith difference of opinion with someone. It’s very difficult to have that sort of conversation over the internet when you can’t do kind of real time adjustments and you can’t see all the bits of it and feel how it feels when you cross the swords. OK, so say you want to send people to events, so how would you select the people who get to go?

PM: OK, so actually, the way I would do it is completely random. People would have to apply. Making the assumption that they would not go to the event if they didn’t have the scholarship to do it. So that would be my basic assumption. That’s trusting other people. Because then you would much more likely get in a new mix of people. The idea of this would be people that wouldn’t go to an event otherwise, I figured this was a fantasy anyway. Maybe I’d put the money into advertising to get people to go to the event. But the idea is that I would want to promote the idea of and actually not even a tournament. Non-tournament oriented events, you know, think things like WMAW that might have a tournament component to it, but the idea is that it’s more of an exchange of ideas.

GW: Because I was going to ask, how do you select which events are eligible for scholarships?

PM: Yeah, that’s yeah. Again, this was fantasy, right? WMAW has an unlimited number of people, but that wouldn’t work either. Maybe, you know, here’s an idea I just thought of right now and again, because it’s completely fantasy mode. It’s going to be the equivalent of the Willy Wonka golden ticket. It’s an event by invitation only. And automatically, event regulars would get invited, but then I would send out random golden tickets throughout the world, and if you’ve got a golden ticket, you would get to come to Pamela Muir’s Martial Arts Factory.

GW: Fantastic. Yeah, that’s a great idea.

PM: Because we’ve got a million pounds. You never said this had to be a practical solution.

GW: No, I didn’t, no.

PM: It’s going to be Pamela Muir’s factory and you get a golden ticket. There will be people that have standing invitations, people whose books line my bookshelves and then if you get a golden ticket, you get to go and hang out with these people and learn in person.

GW: It’s funny, most people who I ask that question of will come up with something along the lines of getting people who don’t get to go to events normally to go to events, either something about making an event move around the place so that people can find it locally or scholarships for getting people to the events or subsidising the event itself to make the event cheaper or offer to provide accommodation at events or one brilliant suggestion was childcare at events.

PM: That is brilliant.

GW: I have forgotten which of my guests mentioned the childcare thing. I’ll put it in the shownotes because that exactly is brilliant. Because I’ve once or twice been seen students with babies at events. People always say, Guy, you should bring your kids. My kids have no interest in hanging around at a boring old sword fighty convention. They’re not into that. So it would be a crap weekend for them and a less good ones for me because I would be spending time basically feeling guilty about my children being miserable and being sort of distracted from what I’m supposed to be doing there. Or I could do it separately, like I go to this event which they’re not interested in. I do that and then some other weekend, I take them somewhere else, but just having childcare at events would make it a lot easier for a lot of people to come.

PM: Absolutely. I was very lucky. You know, my kids are now grown and flown. Both my sons are married. When I first started going to events they were school age. And luckily, I had a very supportive husband who is like, this means a lot to you go.

GW: That’s what husbands are supposed to be like.

PM: Yeah, I’m very lucky. He goes off and he travels doing half marathons.

GW: All right. Okay.

PM: So it’s a fair trade.

GW: I would definitely take the sword fighting event over having to do a half marathon. That’s a long way to go without a bicycle. OK, well, thank you very much for joining me today, Pamela, it has been lovely talking to you and I have to have a lot more thinking time to come back to you about the maths stuff.

PM: OK, well, just nice to see you. I hope to see you at a real event in person sometime.

GW: I might need a scholarship.

PM: Give me that million pounds and you’ve got it.