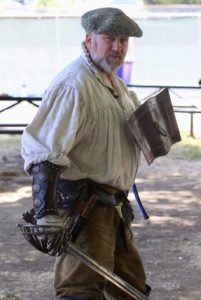

GW: I’m here today with Steaphen Fick, who is a historical martial arts instructor and a fight choreographer, and also an old comrade in arms since we met in Edinburgh in the nineties. He founded the Davenriche European Martial Arts School in Santa Clara, California in 2000 and it is still going 22 years later. We will definitely be talking about how he managed that. Academically, he is perhaps best known for his interpretive work on Joseph Swetnam, and we’ll be talking about that. And he’s also well known for his armoured combat with a longsword, specifically half swording. So, you can find his school at swordfightingschool.com. I’m very glad I got the swordschool.com URL before that. Without further ado, Steaphen, welcome to the show.

SF: I’m so glad to be here, my friend.

GW: It’s been ages, hasn’t it?

SF: It has. And it’s always a pleasure to talk with you and hang out with you.

GW: We have been friends now for more than half my life.

SF: Yeah, we met in 98 or 99.

GW: Something like that. So just to orient the listeners, whereabouts are you at the moment? Are you in Santa Clara?

SF: I’m in Santa Clara, California, right by the San Jose International Airport.

GW: Okay. That’s convenient.

SF: So we are about 40 minutes south of San Francisco. So right in the heart of Silicon Valley.

GW: That’s fantastic. So lots and lots of very rich annoying people driving Teslas.

SF: Yes. I have lots of techies in my school and one of the things that is fun about it, is because I have so many techies and engineers, they love the technical side of the art. So more than the crash and bash, they want the hows and the whys. And that’s one of the things I love, love, love, love talking about.

GW: Okay, well, we’ll definitely dig into some of that, but let’s start at the beginning. When we first met, pretty much all you did was armoured combat. How did you get started with that?

SF: When I was 18, I was invited to a Renaissance fair, and then just before I turned 19, I was invited to a fight with another group that was in armour, and I had no clue what was going on. I thought I was going to be out of armour and just run around with my little foil and poke them in holes. I didn’t realise they were going to put me in armour as well.

GW: Okay.

SF: So they put me in a suit of armour that didn’t fit me, gave me this monsterly really heavy sword because we made them all out of Leaf Springs at the time. So these were beasts.

GW: I remember Leaf Spring swords!

SF: Ten pound swords is what we fought with.

GW: That’s like nearly three times as much as they’re supposed to weigh.

SF: Oh, right, right. But it’s all we had access to.

GW: Yeah, sure. I remember.

SF: So the only instructions I got for my first fight were they’re going to try to back you up. Don’t let them. So I screamed and ran at them and they never used a sword on me once. He hip threw me three times. I was hooked. But one of the things I love most about what you and I do, this weekend, the guy that I had my very first fight with was staying at my house because he was in a rugby game. So I got to spend the weekend with my friend who was my very first sword fight.

GW: Wow. And he threw you over his hip three times.

SF: Yes.

GW: In armour.

SF: In armour.

GW: It hurts when you hit the ground.

SF: When you’re eighteen, you heal very quickly. I bounced well.

GW: Yeah. And then that kind of got you into what, sort of Renaissance Fair type armoured combat stuff? Or it more historical?

SF: No, it was all crash and bash. So it was kind of like Battle of the Nations. But with less rules.

GW: Okay.

SF: I mean, at one point I remember one time I had a guy reach into my, we had no gorgets. I watched a sword go up one guy’s nose one time, but I had one guy reach into my breastplate and try to squeeze my trachea to knock me out that way. And so I whiled away the way the time while he was trying to choke me out by stabbing him in the groin with a trident.

GW: So let this be a lesson to anybody listening. If you want to choke out Stevie, what you have to do is take away his trident first.

SF: So that’s how I grew up and that’s how I learnt to fight. There are old instructions written by Geoffroi de Charny, one of the greatest knights of Christendom in the 14th century. And some of his advice to young knights was, before you go to war, you need to hear your bones crack and see your blood run in the lists. And that’s how I learned. So that’s how I grew up in the European martial arts.

GW: You know, I’ve often told my students, I’ve broken bones doing this so that they don’t have to.

SF: Yeah, I like to tell my guys, pain is the best teacher, ideally somebody else’s.

GW: Yes, exactly. Yeah. I’m not a fan of, like, pain during training. I mean, if something hurts, you’re probably doing it wrong. But, yeah, there’s a certain, like, getting whacked with a sword commands your attention in a way that a verbal instruction does not.

SF: It is true. It needs to be safe. But it also needs to have an element of respect. I don’t want to say fear. I don’t want to say fear, but we are respect and edge. I think that’s important.

GW: Okay. So how did you get from crash and bash to a pretty sophisticated interpretation of Fiore’s armoured combat plays?

SF: So what happened was I got married in 98 and for a honeymoon we went to Europe, to Edinburgh.

GW: And that’s where we met.

SF: That’s where we met, because I was there in like 96 and I wandered into this little tiny shop on High Street, and I met this crazy Scotsman making shields. And that’s where I met Paul.

GW: Right.

SF: And then in 98, we went back for our honeymoon for two weeks. I took my wife, my sword, my dagger, and came back with my wife, my dagger and two swords.

GW: Okay.

SF: And that’s where we met. And then in 99. I knew I needed to learn more. And so I went back with my bride and we retired for six months.

GW: I remember. You came and visited me in Finland then.

SF: Yeah. I needed a master and I knew it. And I went to Europe to find a master. And that’s where I got to learn with you, with Paul, with Gareth, with everybody in the DDS. And I competed. I studied with you guys, and I competed in everything I possibly could. And that’s where we did our reenactments and our tournaments.

GW: I remember you would fight anybody, any time, with anything.

SF: Yes. And because I believe in the concepts. Understand the concepts, and you can use any tool because your head is your weapon. And so that’s why I went to Europe, and that’s when the transition really began. And that’s also I met, Gerard Kirby, for the first time.

GW: Right.

SF: And he was just back from Italy and he had a copy of Dürer and a copy of Fiore. And I looked at Dürer and I looked at the pictures and I go, how did he get there? Why is he doing that? That makes no sense at all. I looked at Fiore, go, oh, yeah, I’ve done that. I’ve done that. Oh, I’ve had that one done to me, I didn’t like that. And so I recognised this stuff in Fiore because it’s the way that I learned through trial and error. It’s similar to what I learned in trial and error. And so that’s why I focus on Fiore in my studies, because it’s things that I learnt the hard way.

GW: Albrecht Dürer’s book, I mean, it’s really good. There’s lots and lots of really useful stuff in it, but it’s not nearly as explicative as Fiore and there’s a lot more fancy stuff in it than Fiore, which is pretty much straight to the point.

SF: Yeah, Fiore is battlefield stuff and don’t die. And because of the way I learned, when you got a guy reaching into your armour trying to choke you out by squeezing your trachea, it gets to be an interesting fight. I mean, at one time I had a guy sword slide into my breastplate, so I had his sword I could feel against my chest. And then he hip threw me. These were some crazy fights that we had. And it’s very similar to what Fiore teaches. It resonated with me.

GW: Interesting. So you’ve been studying Fiore since, what, about 2000?

SF: Yeah. Yeah, about 2000 is right after I got back from you, from the UK. I started really working on understanding it from a practical standpoint.

GW: Right. Okay. On that six months retirement/vacation thing you came to visit me in Finland, I recall, because I was in Finland briefly. I think there was a moment there where we, with no clothes on, went into the lake and then we came out of the lake and it was freezing cold. And we stood on these rocks and we swung swords around. And there was like an, OK, this is what we should be doing with our lives moment, right?

SF: Yeah, it was existential. Looking over the lake everything felt right.

GW: Yeah.

SF: It was an amazing experience. I still tell people about it regularly, except the whole butt naked over the lake kind of thing.

GW: Well, I mean, but now all the listeners have heard the whole thing. Okay, let’s just put that in a little bit of context. In Finland, taking all your clothes off does not mean anything like what it means in the UK or the US. I mean, I’ve been to parties in Finland where the sauna was on, of course, because it’s a party. Why would you not have a sauna on if you have a sauna? And so people were going to sauna during the party and people would like to sort of wander up to the buffet table and help themselves to food or whatever, literally stark naked and dripping wet. And no one thought anything of it.

SF: It’s just it’s a different kind of culture. And it was being there in the woods, freshly out of the sauna, out of the lake. Everything felt right. And now look where we are.

GW: I know. So what actually prompted you to start your own school?

SF: I was actually a firefighter. I don’t know if I ever told you this.

GW: Yeah, I knew you used to be a firefighter.

SF: Yeah, I was a firefighter EMT. And then I left where I lived to move up to the Bay Area to marry my bride, Susan and I was up here after we got back from Europe, I was in training and testing to go back into fire. And as I was testing, one of Susan’s friends asked me if I could teach her 15 year old son sword fighting. And then he brought some friends. And now all of a sudden I’ve got a group of young people that I’m teaching sword fighting to. And I had to make a decision, did I want to be a sword fighter or a firefighter? And just as I had this group coming together. I got called back for a second interview with the fire department. So it was a real question. Sword fighter or firefighter.

GW: Why not both?

SF: Because as a firefighter, I would be out of the area for months at a time. So I couldn’t do both. And I think I made the right decision.

GW: So you decided sword fighter?

SF: So I decided sword fighter.

GW: Did you mention that in your second interview or did you just not go?

SF: No, I was called back with all the other people. I just didn’t go because I made the decision to follow my dream, not my expectations.

GW: But, you know, it’s a funny thing. Like kids growing up. One of the things kids traditionally want to be is they want to be a fireman. Because it’s cool and brave, and you save people’s lives, and you put out burning buildings and you climb up ladders and you have a kind of armour and stuff. So you got to be firefighter first and then switch to being a sword fighter. That’s a pretty good selection of careers.

SF: It went the other way. I was a sword fighter and then the company that I fought with broke up and I lost all my best friends.

GW: Hang on, were you getting paid to do that?

SF: No, no, I wasn’t getting paid for sword fight. I was doing the Renaissance fairs tournaments.

GW: Right.

SF: And before that I was in the army and then I was travelling, doing the sword fights. And when you’re in the atmosphere like the military or firefighting or fighting in full armour. You hold your friend’s life in your hands because you need to be in control. And then of course also the adrenaline of being in a fight and then the company broke up and I was lost. I needed that camaraderie. And so I became a firefighter to find it. It was either firefighter or police officer. And I went with firefighter.

GW: Yeah, probably more camaraderie in firefighting. There’s less personal interaction with people. Yeah, it’s a bit complicated being a police officer.

SF: And I wanted to be the hero. You are the knight, the hero, the thing.

GW: Yeah.

SF: So firefighting was perfect for it. But then I went from sword fighting to fire fighting and back into sword fighting.

GW: Okay, so you had this group of teenagers and you were teaching them sword fighting. How did you transition that into a business that’s been going now for 22 years?

SF: Like every school, club, I started in my back yard and in parks. And in and my garage. Then as it grew, I outgrew those areas. And so I started looking around, and I think I had the first full time dedicated Western martial arts school in North America. Because I rented a 3000 square foot back end of a fruit packaging plant.

GW: Okay.

SF: So I had 3000 square feet that smelled of pineapple, onions and guano because there were bats. Some of the people that were there still refer to it as the bat cave, because they associated it with my school.

GW: Okay. And are you still in that same place?

SF: I am not.

GW: Well, we’ll take this chronologically. OK, so you found this space and you rented it to run your school out of? When was that? Do you remember the date?

SF: That was 2002.

GW: Do you remember the month?

SF: I want to say it was spring, so probably April, May.

GW: Okay. Yeah, that’s about a year after I got my space in Helsinki. I got mine in June 2001. We were very early to be getting a full time dedicated space.

SF: Yeah. Because everybody out before this and it’s still very common. People that run clubs rent space from dance studios or other martial arts schools.

GW: Yeah. In my case, I started out renting school gyms, like high schools, primary schools.

SF: Yeah. I couldn’t do that because California. U.S. doesn’t really rent out very well like that. Not for regular.

GW: Sure. Okay. So you rented this space and then what happened?

SF: So I was there for a couple years. But then I had to move after the second time, I had to call 911 for somebody, because it was not in a good part of town. So I had to call emergency services.

GW: For other people not your students?

SF: Yeah, for other people.

GW: Okay.

SF: So it was time to move. I moved to a warehouse that I was in for a year or two, and then they tore it down and built condos. So I had to move out of that one. Then from there, I moved into a warehouse on a street called Nutmen. Here in Santa Clara. And I was there for about six years. And during that time, I actually rented the warehouse next to me as well and tore the wall down between the two. Which to follow the sequence of how everything should work, the first hole put in that wall as we were tearing it down was made by a mace.

GW: So you thought, hang on. This wall is frangible. Let’s just smash it down.

SF: So that’s how we opened up the two warehouses and then I outgrew that. So I moved to another place. Which was only about two blocks away, was there for another five or six years. Outgrew that and then moved to my current location, which is 8700 square feet.

GW: Bloody hell, that’s enormous.

SF: It’s massive. We have indoor archery range. We can throw axes. We have an axe range and a knife range. We also built modular walls. So once a month we are also an airsoft field. We have games that we can set up the walls to set to make maps and rooms. And because they are modular, the players never know what they’re going to walk into. So it’s impossible to memorise the map.

GW: So your airsoft thing is basically a separate club that you’re running out of your school or do you rent it to an airsoft club, or how do you do that?

SF: I run it, we run it. We’re called the DSOC Killhouse, Davenriche Special Operations Command course. So we are we are the Killhouse.

GW: And just to put this in perspective, 8700 square feet is approximately 850 square metres, something like that. That is gigantic. That is three and a half times the size of my salle in Helsinki.

SF: We have a 5000 square foot training floor. Large armoury, that is floor to ceiling weapons. A library with about 1500 books in it.

GW: You better have my folks in there, sir.

SF: Of course.

GW: Oh good. Otherwise, this would be a very short conversation.

SF: As well as a padded knife and grappling room.

GW: That sounds impressive. Business wise, 8700 square feet is not cheap anywhere.

SF: It is not.

GW: So if you’re up for talking about it, one thing I’m very keen on doing is because a lot of people think, okay, yes, I’d quite like to start the club, I’m fed up with my day job, I want to teach historical martial arts for a living, but there are very few people who have actually done it successfully. And you and I would be two of those people. So how did you make it work from a business perspective?

SF: One of the things I like to do. I’m glad you asked this. I like mentoring people that want to get into the business side of it.

GW: Yeah, me too.

SF: One of my goals is when you tell somebody that you do martial arts, they say, Cool. Eastern or Western?

GW: Right. Yeah.

SF: And so what I do is, one of the things I tell people right off the bat is look outside of your industry, because there is so much information that people have worked on, tried, been successful, also tried and failed. Find that information, utilise that information and adapt it to our industry.

GW: So you’re saying like find a successful model and copy that and adapt it as necessary to your specific conditions?

SF: Yes. My wife is a realtor and she is a member of a coaching company that I was also a member and taking professional coaching to build my business. And while it was real estate, I was able to take their techniques and their philosophy, adapt it to the school and build the school. And we currently have about a little over 100 full time weekly students. As well as I run workshops that on one weekend a month we run separate workshops. We’ve got another 15/20 people that are regulars to that. We also run the DSOC Killhouse, which brings in another avenue of income. And I also work with businesses around the Bay Area to run their teambuilding events.

GW: I’ve done a little bit of team building and honestly I didn’t like it. They come at it from such an odd perspective that it just it doesn’t work well for me.

GW: Can I come back to the real estate thing. With the business of real estate is somebody wants to sell the house, somebody else wants to buy it. And a real estate agent either works for the seller or for the buyer, or in Finland is a kind of neutral party in between and basically connects. I mean, if you buy a house every two years, you’re weird, right? Or you’re a professional flipper. Shall we say every ten years, they get one sale every ten years for that particular client. Whereas you have students who are coming weekly. Maybe several times a week for a kind of continuous thing. So I don’t see any relationship between these business models. Educate me Steve, educate me.

SF: Regardless of what your industry is, the only reason somebody is going to work with you is because they trust you. So what you’re really selling is yourself and your relationships that you can develop with those people, because if they don’t trust you, they’re not going to want to work with you. In real estate it is often the biggest financial choice that some people ever make, because they only buy one house and they live in it for their whole life.

GW: Yep.

SF: So you want to really trust the realtor that they’re not going to lie and steal and just leave you in a really bad place. For you and I, we need to sell ourselves and our trust because the people that we’re working with, expect us to educate them, but also to keep them safe and to have fun. Because if you’re not having fun, why would you pay for something every month?

GW: Right.

SF: So we are in the business of relationships.

GW: Okay, I can see that.

SF: And that’s what I learnt from the real estate industry. And there is a big difference between people that are in the real estate industry for the cheque, versus people that are in the industry for the relationship. My wife is a generational real estate agent. What that means is she worked with people that bought houses, then worked with their kids, then worked with their grandkids.

GW: Wow. Because if you want to buy a house, go to Sue because she will look after you.

SF: Yep. Or if you want to study martial arts, go to somebody that will develop the relationship. Not just, I’m going to see you at class. And then that’s the last thing I’m going to see of you until next class.

GW: Okay. So, I mean, one thing I always did when I was running my school in Helsinki was we had some regular party nights and pub nights and so students were socialising outside of the school, which is a kind of fairly obvious and basic interpretation of what you just said. Are there any, like, specific ways of doing this?

SF: There certainly are. In fact, one of the things in the coaching company that they talk about is client appreciation parties. And you categorise your database, you have A-pluses, A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s. A-pluses are the people that in the real estate industry refer you multiple times. A’s are people that refer you sometimes. B’s are people that you can train to refer you. C’s are people that you can bring up to that B level. And D’s are people to delete.

GW: Okay.

SF: For us, A-pluses are our current students. A’s are our leads. B’s are people that we meet and talk to. And so I have client parties, although we call them a solstice feast or we have a summer solstice feast and a winter solstice feast and we light the school by candlelight, eat, drink and lie to each other. Just a lot of fun we’ve got and it’s like a medieval feast.

GW: So you encourage people to bring their friends?

SF: Family members. These ones are just for the students and their families. But then we do other things where we have lots of birthday parties for people in the school that we bring all their friends in. We have other events that where we do charity parties. People come in and you get tickets. This is a new one that we’re working on. You come in, you buy tickets, and you turn in a ticket for throwing an axe. You turn in ticket for throwing a knife. You turn in a ticket for throwing a javelin. You turn in a ticket for shooting some arrows. You turn in a ticket for sword fighting.

GW: Okay.

SF: And then all the income goes to a local charity.

GW: That’s a great idea. That’s a really good idea.

SF: This helps lots of people. It helps the charity. It allows my students to come in and spend more time playing with toys. And it brings in new people that get to see how much fun it is. The other thing I do is on the back of my business card. I think I have one right here. I’m going to show you. I know we’re not videotaping this one for everybody else. But on the back it says, “Bring this in for three free lessons. Referred by…” And then they write on who referred them. So I can personally thank whoever passed that card on.

GW: That’s clever. I did for a long time on the back of my business card it had a 10% off a beginners course. But there wasn’t a referral thing. The referral thing is genius.

SF: And that’s what I learnt from the real estate agents.

GW: Huh. Okay. Yeah. There will be people who know nothing about business listening to this thinking, this all sounds a little bit scammy. And there are certainly people who use these techniques in a scammy way or for scammy purposes. But I think it’s probably worth flagging up that it’s actually genuine. They genuinely trust you because you’re genuinely trustworthy. And the way I think of it, when any kind of marketing thing that I do, I want to be absolutely sure that the people receiving it will think that I’m doing them a favour. Right. So, for example, when I launch a limited time discount thing for an online course I’m launching or something like that. I routinely get emails from my mailing list thanking me for sending them the discount and telling them about the course, which tells me that at least some of the people getting the emails are the right people to be sending them to. So I guess, I think for me the distinction is if you do something for people, that’s okay. If you do it to them, that’s not.

SF: And one of the things that they talk about, and I’m a big believer, is you get what you want by helping other people get what they want.

GW: Yeah, absolutely.

SF: And so my goal is to help people get what they want and what they want, the ones that come to my school, is most of us grew up watching movies or reading books or playing DnD and loved it and, wait, you mean I can do it for real?

GW: Right, yeah.

SF: And some people want to get into the tournament side of it. Some people have no desire whatsoever to get into tournaments. Some people have no desire whatsoever to even do free play. And it’s their choice. And I give them an avenue to what they want, not what I want.

GW: Right. Yeah. I look at it as I’m a Consulting Swordsman and it’s my job to help people accomplish their sword related goals. That’s how I articulate it. And it doesn’t actually matter to me what those goals are. If they want to train for a tournament I can help with. They’re probably actually better off going to somebody else for that because that’s not really my area of speciality. I’m not that interested in it, but I could certainly do it. And if I’m the only one available, then yeah, they could do a lot worse. It doesn’t actually matter to me what the c the starting position is or what their goals actually are, so long as obviously the goals are like ethical and reasonable.

SF: When I’m on set, whether it’s on stage choreographing or on a TV or movie set, I always tell the stunt coordinator or director, I’m hired help. You tell me what you want, I’ll make it work for you. The only time I’ll say no is when it’s a safety issue.

GW: Right.

SF: Otherwise, I’ll make it work and get you what you want.

GW: I do the same thing when I start a seminar. I get all the students round and I say, okay, why am I here? What is do you want? If this is their first seminar with me they kind of stand around a bit surprised. And I point out that, you know, Salvatore Fabris was fencing master to the king of Denmark. Who is in charge in that relationship? And if the king wants to do parry ripostes today without any footwork because his legs are tired, then that’s exactly what they do. So again, that’s where I sort of got the model of consulting swordsman, because the whole thing about martial arts instructors, is our cultural perception of it is very heavily influenced by martial arts instructors that we’ve seen on the screen who are almost invariably teaching karate or kung fu or something like that, where the social relationship is completely different. I’m like a plumber. I don’t have to like the colour of the bathroom I’m installing. It’s your bathroom, it’s your house. But I’ll make sure it doesn’t leak.

SF: I was just reading something about the saying the customer’s always right. That’s only part of the saying. The customer is always right in their taste. You may not like the colour of the suit that they’re buying. You may not like the hat. It doesn’t matter. It’s their taste. Our job is to facilitate so that they can get what works for their taste.

GW: Yeah, that’s very true. Yeah, it’s funny. I segment my client base, customer base differently. There are four groups. Any given customer is either sophisticated or not sophisticated. In other words, not how elegantly sophisticated they are. Are they an experienced purchaser of this kind of resource? So in other words, have they taken martial arts classes before? Have they done other kinds of training before or whatever? I mean, generally speaking, like a training sergeant in the US Army is going to be a sophisticated customer of my products because he’ll spot bullshit. Which I would hope wouldn’t be there. But, you know, there’s sophisticated and unsophisticated and most beginners are unsophisticated. But sometimes they have lots and lots of background in other things, which actually makes them a sophisticated customer. And then OK or not OK. An OK customer is someone who respects my time and their own. Pays appropriately and on time. And a sophisticated customer is likely to be quite demanding. But those demands will be reasonable. Whereas the not-OK customer is someone who, for example, rips off one of my books and sticks it on the Internet. It’s just a for instance.

SF: Or I had to beat one student out of my school. He liked to go really hard on women. And then I was like, “Why don’t you and I play?” And he backed out of the ring. So I turned around to walk back into the ring, and he attacked my back. And I heard an inhalation. And I turned around and covered my back. OK, I can play that game with you. So I backed him into a pillar and proceeded to beat him into a pillar. And I never saw him again. I can play that game too, if you want.

GW: Yeah, it’s funny. As a martial arts instructor, if we have to do that, we have at some level failed to spot the problem before it occurred. But, we have to be able to do that if necessary.

SF: But the other thing I would say, I want to backtrack just a little bit.

GW: Yeah.

SF: One of the things I tell people that are looking at starting a school and going professional. Get a credit card company. So it’s automatic payments.

GW: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

SF: You need automatic payments, otherwise you can never count on the money being there when you need to pay rent.

GW: Right. And to be clear, it doesn’t have to be a credit card company. I mean, I set it up with my students in Finland. They have very simple monthly standing order things that they would use. They didn’t have to use a credit card, but you have to have some system for automating payments. I remember my guys in Seattle told me that all of their financial problems were solved when they started using I think it was PayPal and the default way of paying training fees was a standing order. The money just left the account. They could cancel it at any time, but they had to decide to cancel it rather than decide to pay. And it makes all the difference to cash flow.

SF: Every summer in my early years. I wanted to quit. Because people would go on vacation and not pay their rent. And I’m like, I got to figure out how to pay rent.

GW: Yeah. I once had a student come to me and say that he’s paid up for the month, but he’s going on vacation for a couple of weeks. So he can’t be training. Can he just pay half? And I’m like, well, I don’t have to just pay half of my salle rent just because you’re not coming. So that’s a no, and he quit. And there’s another example of a not-OK customer. The OK student understands that they’re not just paying for your time right now. They’re paying for the school to continue to exist. Because if people like them don’t show up and pay their training fees, the school will cease to exist.

SF: I’ve had people ask me that same kind of thing. I say, I understand where you’re coming from, but no, because I want to have doors open for when you come back.

GW: Right. That maybe a slightly nicer way of putting it.

SF: I think I have always been a little nicer than you, Guy.

GW: That’s probably true. I find though like the best filter for the not-OK customers is the beginners course because if you make it nice and friendly and supportive and clearly we’re all in this together, then the people that want a different culture will go somewhere else and get it. It’s maybe a bit too nice for them.

SF: That’s okay, too.

GW: That’s right. Absolutely. And I also actually have students who come and ask for a particular style of training. And I’m like, look, I just we just don’t do that here. But I have a friend who runs I think what you’re looking for over there, go train with it. Yeah.

SF: Yeah. I refer people all over the country. And that that’s the other thing about being in business. Understand that there are enough clients, enough students for all of us.

GW: That’s right.

SF: I don’t need to be so stingy that I’m afraid to refer somebody to someone else because it might take a little bit of money out of my wallet. And not everybody works well.

GW: Yeah, if a student ends up deciding that they’re happier doing Escrima. Then off they go doing Escrima and that’s great. And I have friends who teach Escrima, who do it very well. And off they go, brilliant. And some students do both.

SF: I have four different teachers that work for me. And one of the things I like about having multiple instructors is that my style of instructing may not be right for everybody. And it’s all right. It’s no reflection on me, nor is it a reflection on the student. It’s just I may not be the perfect fit. I was on movie set one time doing a tough role. I was the sword instructor.

GW: You had to dig deep for that one.

SF: And I asked the director, okay, what kind of instructor do you want? I can be Mr. Miyagi or I can be Cobra Kai. Which one do you want? Because I can give you either one on set. In my school if somebody wants Cobra Kai, I’m the wrong fit for them.

GW: I guess this is really about getting and keeping the right students. Two things about moving schools from one place to another. Firstly, how do you know when the space isn’t big enough and therefore is worth upgrading? And secondly, do you lose students when you move from one place to another?

SF: When I’m working in a school or a facility, the way I find if it’s not going to fit for the amount of people I have anymore is when swinging a sword becomes dangerous to those around. There’s not enough room.

GW: Sure. I get that, but there are other things you can do rather than just move to a bigger space. I mean, you can, for example, split the classes up. Instead of having one class on a particular night, you split into two classes.

SF: But where I’m at right now is on Mondays we start classes at 6 p.m. and end at 10 p.m. Each class is one hour. But it’s not uncommon to have two or three classes going on at the same time. Two or three different classes. Longsword is our most popular class. So we have a 6 p.m. longsword, but then at seven we have a sword and shield class and a dagger class going on at the same time. At eight we have a grappling class and another class and then nine is just longsword again.

GW: Oh wow, that’s pretty busy.

SF: Yeah. And then on Tuesdays we have our longsword class and a kids longsword class. We call them the Dragon Slayers. Our Dragon Slayers are ages 8 to 13 and then 13 they move into the adult class. So we’ve got those going on at the same time. So we have multiple classes going on at the same time. And if I can’t figure out a way to get these classes to work.

GW: Then you need a bigger space. So do you lose students when you move from one place to another?

SF: Not generally. As long as they don’t go too far. I mean, I’d love to bring the school down by where I live, but in the Bay Area, we judge distance by time, not by miles. So there’s heavy traffic and congestion. So it would be an extra 30 minutes on top of the normal time, and then I’d lose more than half my students. So it’s not viable. But as long as I stay in the same area, I don’t lose students. Not enough to affect it.

GW: I’ve only moved salle once. I rented this space in Helsinki in 2001. And then the school kind of expanded and contracted and expanded and contracted. And it was like just too big for the space by about 2007. And the space across the hall that was more than twice as big became available. And so I bought it. We moved literally across the hall in the same building. You go to the top of the stairs, turn right into the old, to the left and to the new one. I say “new salle”, it’s been like 14 years, longer. But I think it must be a coincidence, but there was a catastrophic drop in attendance for the next three months. And I thought, oh, my God. And of course, the expenses of running a place that’s twice as big are twice as much and the risks and what have you. And, you know, I secured the mortgage on my apartment and everything, so it was like massively risky and stressful. But yeah, it was like three months, or so. And then suddenly attendance picked right back up again. I think it must be a coincidence. I think that was probably going to happen anyway.

SF: Yeah, I think our job is just to get, get people in the door. That’s everybody’s job. Then your job, my job is to keep them.

GW: I disagree. My job is to give them a true and faithful representation of the art as I see it, so that they can make an informed decision about whether it’s for them or not. I don’t actively try to keep them.

SF: I keep them by keeping them entertained and learning, but I get them in the door through student referrals. But I also use things like Groupon and Amazon has some things where you can sign up on my website for three free hours.

GW: Yeah.

SF: Or you can go to Groupon and get 4 hours for half the price of a month long membership.

GW: Okay.

SF: And so either way, I get them in the door.

GW: Yeah. And more importantly, you get them in the door for more than one session.

SF: Yes. Because if it’s only one, they don’t get the sense.

GW: Yeah.

SF: So that that’s what I do to get people in the door. And then I also spent years putting together a curriculum. So each class we have longsword, dagger, grappling, side sword, rapier, sword and shield. “Be Safe”, which is a modern day self-defence system based on Fiore. But everything ends with you running away.

GW: Good.

SF: And then lightsaber which is a combination of longsword and side sword with flashy twirly bits.

GW: You know, I just interviewed the man who taught Samuel Jackson how to use a lightsaber, and he was the body double for Count Dooku in those early Star Wars.

SF: Oh, Kyle.

GW: Yeah, you know Kyle, of course you know Kyle. I’m not sure when his interview will be coming out relative to yours, but fascinating. I would say from your list, smallsword is a glaring omission.

SF: I don’t like smallsword.

GW: How can you say that! How could you say that? It is the most vicious, nasty, like, sadistic and twisted way of murdering a person you could possibly imagine. You stab them full of little triangular holes.

SF: Yeah, oh, I also do cutlass, tomahawk, those things. But cutlass and sabre are pretty much where I stop. Military sabre.

GW: Steve, Steve.

SF: I used to fight, like you said earlier, I’d fight anybody with anything. And I remember fencing you with smallswords.

GW: Did I put you off?

SF: I mean, I could pick up anything and fight with it. And I was so frustrated and angry. Oh, you trounced me. It wasn’t even close. But it’s not like I just laid down and you poked me a lot. I made you work a little bit for it. But it was so frustrating

GW: I’m sorry. Well, okay. So if I’d let you win a little bit, then you might have taken up smallsword and had a properly well-rounded curriculum.

SF: Maybe.

GW: For the smallsword people out there, I do apologise for turning Stephen away from the true and noble path. Well, speaking of, like, stabbing people, you’re quite well known for your Joseph Swetnam stuff. In fact, the last time I actually saw you in person, if I remember rightly, was in Vancouver. And you were teaching a Swetnam class. What drew you to that raging misogynist and his rapier ways?

SF: Oh, he is a total jerk, but really good at what he does with the rapier. And that’s the other thing I would say to everybody. Find a mentor. You can’t do this on your own. Even Tiger Woods has a coach. My mentor started me on rapier and dagger from Swetnam back in ‘97. He was a fencer, sabre fencer, who started in 1942.

GW: Bloody hell. What was his name?

SF: John Hudson. He started me on rapier and dagger from Swetnam and then gave me a copy of the manuscript. And so I just followed that and worked on getting the system down and playing with it and then researching him. Because, as you said, he was a raging misogynist. But what’s interesting is when he wrote his plays, the rebuttals, this young lady says, I thought it was somebody important, but it was just a fencing master from Bristol. That’s a seaport. And when you look at the way he says to stand with your feet in line. Everybody wants to stand like modern fencing where you L or T, but if you stand with them online, it works really well on a moving deck. So I think he was a gentleman adventurer of the 16th century.

GW: Okay.

SF: And I really enjoyed the way the motions and the, coming from an armoured background, it didn’t have this funny bent over thing like Fabris. It was much easier on my body coming from armour to stand more upright. And I remember one of my favourite tournaments was an instructor tournament at ISMAC. It was you, me and Tom Leone.

GW: Oh, God, I remember. It went round and round and round.

SF: You beat me, I beat Tom, Tom beat you. And we did this like three times. And finally, Gerard Kirby was like, we’re just going to call it here. Everybody’s a winner. Because we kept going around in a circle. And so I dig Swetnam because it allows you free movement that can work on a moving platform. So whenever I’m like on a train or a bus or something, I actually stand in Swetnam’s footwork and it allows me to maintain my balance on this platform. And it’s also how I practise. But that’s how I got into Swetnam.

GW: Right? Because John Huston told you to and you liked it.

SF: And it was in English and I could read it.

GW: That helps that really. I mean, I think Swetnam’s abiding virtue when it comes to rapier fencing is the fact that he wrote it straight in English because he was English. That really, really makes things a lot easier. There’s a whole layer of interpretation they don’t have to bother with. What makes Swetnam style fencing different to, say, the Italian school of the early 17th century? Because they are pretty much contemporary. Swetnam’s treatise came out in 1617, was it?

SF: Correct. 1617.

GW: 1610. I have a 1610 Capoferro. I’m going to go and get it. Listeners, I’m terribly sorry, but regular listeners will go, oh god, Guy’s dragging this book out again. But, you know, when there’s somebody sitting there in front of me who would appreciate this. This is the 1610 Capoferro. And this this copy of this book Was printed in 1609 or 1610, and it is entirely original and unfucked about with. It is very beautiful.

SF: That’s lovely. I did not realise that it was a soft binding.

GW: Well, okay. Books in that period you bought the pages and then had them bound. And if you were a professional bookseller, you’d buy up a bunch of these printed books and you would bind them in your own particular way, and then you’d sell them. If you are a rich person buying books, because you have this bizarre fascination for buying books and you have your own binder, who would or you would hire a binder who would bind them in the style of your library. So, for instance, Vadi, from the 1480s. Manuscript scholars are particularly interested in Vadi’s manuscript for its cover because it is one of the very few surviving original covers from the Duke of Urbino’s bindery. The publisher of the book, or the printer and the book binder and the bookseller, it was all quite separate. If you studied your smallsword, you would know this because Angelo says that, you buy a blade, then you test it, whatever, and then you have it fitted to the hilt. You could buy a whole sword, but it was also common practise to buy a blade and have it hilted.

SF: Right. Well, we’re getting way off track, but that’s why it’s so hard to categorise the swords, because I might buy a blade in Germany and get it hilted in France and then sell it in England.

GW: Right.

SF: Where did that sword come from?

GW: It came from my house. It’s my sword.

SF: Yeah, that’s right.

GW: Okay. So Swetnam. 1617.

SF: So what makes it different from the Italian.

GW: Or from the Italians? Well, do you think he studied with the Italians?

SF: Oh, I think he did. He says he travelled for 30 years. He went to Cambridge and Oxford, but was only there long enough to tie up his horse. He’s constantly on the move. He’s very English in that he cuts into his thrusts. So unlike Capoferro.

GW: Two things. What is cutting into the thrust? Because the average listener probably has no idea what we’re talking about. And secondly, why is that particularly English?

SF: So English martial arts of that period are very much a bastardised version of Italian.

GW: Horseshit.

DF: I disagree. I think they really are.

GW: Okay. Okay. All right. By English martial arts, are you talking about the martial arts that George Silver is talking about?

SF: No, no, not Silver. No, no, no. Silver is totally English.

GW: Because English martial arts, as George Silver is describing them, are totally English.

SF: No more like medieval. Right. Those are bastardised. We’ll see that in the sabre as well of the 19th century.

GW: Okay. So the average English gentleman of the late 1500, early 1600s is fencing in an Italian style. I think there we can agree.

SF: Yes.

GW: Okay. That doesn’t make them English martial arts.

SF: Okay. So then Silver and that style is all about the cut, fly in, fly out, all that stuff.

GW: Yeah.

SF: Swetnam is very English. He likes to cut more than thrust. He says, use your rapier as you would your backsword.

GW: Okay. Yes.

SF: When we look at Capoferro, he works in primarily seconde and quarte. Primarily.

GW: Most thrusting actions are done in seconde and quarte. Yes, absolutely.

SF: Swetnam cuts in tierce, in third, because he cuts into his thrust. So it’s like a backsword cutting into that thrust.

GW: Okay.

SF: So his guards, like true guard, start with the edge facing the opponent so you can cut into it.

GW: So he’s not pointing at his opponent’s eye, he is pointing above so he can cut down.

SF: Correct. Which coming from that armoured background really fit my mentality. I like to get in close and let them know that their choices were poor.

GW: Doesn’t Swetnam also recommend an incredibly long dagger?

SF: A four foot sword and a two foot dagger.

GW: That’s fucking enormous.

SF: He says you should be able to do a 12 foot lunge.

GW: Can you do a 12 foot lunge?

SF: With the proper size rapier, yes. I actually got my hands on one and I was stretched out, but I could make a 12 foot lunge and recover from it. But it’s like a four foot rapier.

GW: Yeah.

SF: It has too much blade.

GW: Yeah. Okay, so my Rapier has a 42 inch blade from the cross guard to the point. So you’re talking about something that’s six inches longer than that?

SF: Yes.

GW: Okay. Now, I’ve actually done measurements where I lie on my back and extend my sword arm above my head and we get the absolute maximum distance from the outside of my left foot to the point of my sword. Which is the anatomically longest possible distance between those two points. And then put one end of the tape measure on the wall or the wall target, I mark that distance to the ground, make a mark. I put my back foot on it and I can hit the target. That’s using Capoferro’s mechanics. So it is measurably the longest possible lunge you can make for the human body. And of course, I can make it longer by having a longer sword. But I couldn’t make it longer any other way, it is mechanically as long as it can possibly go. And I’ve written this up. I will put a link in the show notes. Or you can search my blog for “Max Your Lunge.” Okay. That said, what is it about Swetnam’s lunge that makes it so long?

SF: Two things. One is the length of the blade. The sword.

GW: That’s an extra six inches.

SF: Secondly, he says that your back foot should stay in place and hold you as an anchor holds the ship in place. He has a lot of nautical references in his manuscript, and coming from Bristol, which is why I think he was a gentleman adventurer on ship. And if you think about the way an anchor holds a ship in place, it rotates around that anchor point. And so if I rotate on my toe, my heel turns in. That gives me a little extra distance as well.

GW: It gives you five extra inches. At least it gives me five extra inches because Capoferro explicitly refers to the turning of the back foot in his lunging play. So there we agree entirely.

SF: He’s got the length of the sword and the turning of the foot, which holds you in place. As the anchor holds the ship, you get longer distance.

GW: That’s the extra six inches on the blade. And those five inches.

SF: That’s a foot almost.

GW: Yeah. Although when I’m doing the measurements with Max Your Lunge, I reserve the turning of the back foot for penetration. It is not enough just to touch the target. You have to actually shove the sword into it. So I have the foot perpendicular to the line of attack on the ground and I can reach the target, but I can’t really hit it. And then with the turn of the foot I can shove the blade five inches in, which is sufficient.

SF: More than enough.

GW: Yeah. Yeah. Okay.

SF: So that’s why he can get that. And I was teaching at SoCal Sword Fight earlier this year, and one of my friends who’s massive. He’s really tall. He has a rapier that he got from Arms and Armour that has a four foot blade.

GW: Okay.

SF: And with that, I could lunge 12 feet.

GW: How tall are you?

SF: I am 5’10”.

GW: Okay. You’re a couple inches taller than me, or an inch taller, as it were. Okay.

GW: So you do that with a cut.

SF: Yeah. So the extension and the cutting helps pull me forward as opposed to just the line.

GW: Okay. I don’t think that’s going to make mechanically any difference to the reach.

SF: It’s not to the reach, but to the explosiveness.

GW: Okay. This is something where we need to get together and actually test it, I think.

SF: Yes. I love Swetnam and the way he uses a dagger. The other thing I like about Swetnam is he tells you four ways not to use your dagger.

GW: Huh? Okay. What are they?

SF: Don’t take it too high. So never above eye level. Your eye level. Don’t take it too low. He calls it his girdle stead. So don’t take your dagger below your girdle stead. Don’t take it too far to the side and don’t take it behind you. Pull your elbow back or follow it behind your shoulder. And if I don’t do those four things, my dagger stays in front of me. And that gives me a wider cone of defence. And because my body is squared up, not profiled, I’m able to just walk my point right in along their sword arm.

GW: Okay. I think that’s one of the really distinctive features of Swetnam. His style is that he’s not profiled.

SF: He is not. He is squared up.

GW: So he’s fighting with the rapier and he’s basically I mean, he’s not like completely square on, although he’s maybe 45 degrees off the line or rather than.

SF: No, he’s squared up because he says to practise his stance, he says, put your heels against the wall with your back touching the wall, step your right foot forward so your heel’s in front of your toes and then bend your back knee. So, your back rests on the wall.

GW: OK, I’m doing that now.

SF: So you’re back touching the wall now. Right foot just in front of your left foot. So you leave the wall now bend your back knee so that your back rests against the wall.

GW: That’s the stance?

SF: Yep.

GW: Oh, my God. Let me get where you can see my feet.

SF: He says you people will say that the danger is that your head is within closer reach to his point than your stomach. Yep. That’s it. Now imagine you’re on a train or a boat and rock forward and back and side to side. Which is very similar to the stance that Fabris teaches, except that he bends forward. Yeah, so we see the similarities.

GW: Fabris would have the feet similarly spaced, but the legs are much straighter and your hinge goes to the hip.

SF: But the stance is the same.

GW: Stance is right in there.

SF: And the other thing that he says is that your knees should be a fist apart. That one took me a while.

GW: The knees should be a fist apart.

SF: Do you know what a fist it?

GW: Yes. So it’s also called a fistmele, which is my grandfather told me this when he was teaching me how a long bow should be strung. And he said that the distance between the inside of the handle and the string when you string the bow should be a fistmele, which was you put your fist on the bow and you stick your thumb up. He said you could also double it by putting a second fist underneath if you want a very high string. Now, I was six or so when he told me that, so I may have misremembered, but I remember that a fist, or a fistmele is usually.

SF: Pinkie to the extended thumb. And that took me a long time because I had to research archery to understand. And again, English, the English Longbow.

GW: Dude, you could have just asked me.

SF: I didn’t know you were that old. So, yeah, one of the things I love about what we do is it’s so much more than the sword. There’s all the research that goes into so many other aspects of the society of the time.

GW: Yeah. It is quite a broad project. It’s like what you’re saying earlier about running a school. It is a mistake to just look within your own field.

SF: Yeah.

GW: I leaned most of what I know about actually making a living doing this from people like, for example Joanna Penn, who’s been on this show, who has nothing to do with swords at all, but she writes books and makes a decent living doing it because she knows how to sell books and what she says, and you’ll like this, is you want to basically give people enough free content that they know you, like you and trust you, and they’re pleased to hear about it when you bring out something they can buy.

SF: That goes back to your making and selling relationships.

GW: That’s right.

SF: One of the interviews I did, I did a thing called the Pandemic Interview series. It was just something during the pandemic. And that’s where I had you on my show.

GW: Yeah, yeah, yeah. You interviewed me.

SF: Yeah. Just talking about a way to talk with people about different aspects. I talked to actors, directors, martial artists. But one of the guys I talked to, a couple of guys I talked to, are professional clowns. One is in Australia and the other one is a professional clown and children’s entertainment specialist. So he does the clown, Spider-Man, Jedi Knight, things for parties. And we talked about marketing. And also valuing yourself.

GW: Right.

SF: So many of us, we love what we do. And there’s a tendency to want to give it away. But if you don’t put a value on it, why should anybody else value it? And so it’s important that you recognise the value that you bring to whatever event you’re doing and they are paying you not just for that hour that you’re there or that few hours, they’re paying you for all the years that you spent working on that. And if you’re doing demonstrations, they’re also paying you for the equipment that you’re using in the demonstration.

GW: Do you remember my friend Nim, the Kung Fu instructor?

SF: I remember staying over at his school.

GW: Yeah, that’s right. He used to say to his students, you don’t pay me for my time because you couldn’t afford it and you don’t pay me for the art because this is beyond price. You pay me to compensate me in some small measure for the pain and suffering I endure, watching you butcher my beloved art. No! That is not how you speak to your students. No, no, no, no.

SF: That’s amazing. You’re paying me to watch you butcher this.

GW: Yeah. I mean, see, I never have a problem putting a price on a book. Because it’s an object and other people have made it. They printed it and bound it and there it is. But it took me a long time to get my head around the idea that I should charge really properly for my time. Get this. For ten years I didn’t raise my weekend seminar prices. A weekend with me was €1,000 in 2000, €1,000 in 2010. And then I realised I had effectively dropped, while improving massively as an instructor over those first ten years, as one would hope, I managed to like basically cut my prices by about 15% or something stupid, right? So I sorted that out. And you know, these days, I raise my prices regularly and all that sort of thing. These days I am perfectly happy to turn down people who don’t value my time.

SF: That’s something that I need to do with my weekend workshops. Raise those, but my demonstrations have gone up every other year.

GW: Yeah. Yeah. Sensible. Thing is, there are people who can pay properly if they choose to, and there are people who simply can’t whether they choose to or not. So I have no problem working for free. I will work for free in all sorts of situations. Like, for example, I recently taught a seminar for a fledgling little group and they couldn’t possibly afford to pay my regular evening fees because, there weren’t enough people. So they paint their usual hall fee and a donation to a charity of my choice. So I worked for free, but they paid a little extra more than they normally would and that money went to a charity and everybody knew that’s what’s happening. So it wasn’t Guy teaches for free. It’s Guy will sometimes work pro bono in service of charity. Which is not the same thing as teaching for free.

SF: The other thing I’ll do sometimes is I barter with people.

GW: Okay.

SF: Because there are people that have skills that I don’t have.

GW: Sure.

SF: There are people that like to do things that I despise.

GW: Like accounting.

SF: Accounting. I have a person that does accounting for me and I trade services with her.

GW: Really? My accountants just want money and so I’ve been paying my accountants since I started, I mean, I when I moved to Finland in 2000, about to start my school, I knew there was no way I could do my accounts in Finnish with the Finnish tax office, blah blah. So I got myself an accountant straight away and I’ve never, ever regretted it.

SF: The other thing to remember is for anybody who’s thinking about doing this, well, this is a business, not a hobby. They are two different things. You have to treat it like a business. But that also means that there are perks. You know, when you and I get together, Guy, and we have a few beers and we talk swords, we’re at work.

GW: That’s right. Business expense. Absolutely. No question. And you know, the equipment for setting up this podcast: business expense. Of course, that is all part of the thing. When I buy a sword: business expense.

SF: When I buy a new computer.

GW: Yeah. Although let the record show, that Capoferro does not belong to my company. That belongs to me.

SF: Actually, most of the stuff in my school belongs to me, and I rent it to the school.

GW: That’s a good way to do it. That’s a very good way to do it. That completely sidesteps the capital problem.

SF: And that way, when I go to sell my school, I’m actually training somebody to take over my school.

GW: Oh, good. Yeah, I was wondering.

SF: That way I can go and spend more time doing movies and TV stuff because I want to get into that side of it. I want to bring what we do to the screen. But I can’t leave if there’s nobody to take over the school. And I know that it’ll be in good hands while I’m gone. Not to say that I’m gonna stop going to the school, it just means I can go in and teach when I want and still get paid.

GW: Yeah. I retired from my Helsinki school in 2015 and moved to the UK in 2016. So I’ve not been teaching there regularly. It’s still running. The salle is still there and still operating. So maybe we should get together and talk how do we do the handover.

SF: Yeah. So, I mean, Johnny is my number one. He’s the one I’m teaching to take over the school. Because I own the stuff and I rent it to the school. If I were to sell the school outright, not only do they get my database, not only do they get my facility, they also have to pay me for the equipment that goes into it.

GW: There’s a rental contract there. That’s a good way to do it. I hadn’t thought of that.

SF: And that also means because I’m an LLC that is one more separation.

GW: Yeah. And you need that. I have a limited liability company in the UK and I have another one in Finland, the Finnish one. I started out as a sole trader and then after about six years I got some good advice and that advice included, no, you’ve got to be a limited liability company. So I switched. When I moved to the UK, I started a limited liability company straight away because you need that, need that legal separation between, particularly as a self-employed person, sitting between yourself and the company. And the company has its own kind of needs and interests and whatnot that you yourself may not want to particularly be involved with.

SF: Right. Yeah. So that’s another reason why I say you have to treat it like a business, not a hobby.

GW: If you want to do it professionally.

SF: Yeah, if you don’t, it’s a great hobby. You want to just go out to the park and meet with your friends and have a study group? Fantastic. Have a great time.

GW: Yeah. And actually, that’s how most people do it. And that’s how probably most people should do it. I have found, because I’ve tried a different hobby into a job before when I was when I turned my woodworking hobby into being a professional cabinetmaker and it made me fucking miserable. It was a bad job for me and I am much, much happier as an amateur cabinetmaker than I ever was as a professional. But the swords, I don’t want to have to go and do something else for a living, I’ve got too much sword stuff to do. And so it has to be a full time job because I don’t want anything else to take up a full time job’s worth of my time.

SF: Yeah. And understand that if you’re doing this professionally, it’s too easy to stop working on your own skills because you focus on everybody else.

GW: Yeah.

SF: So it will suffer. Your skills will suffer until you find a way to continue working on your own skills.

GW: Okay. I know how I did that. How did you do it?

SF: When I go to seminars, I take every class I can when I’m not teaching. Whether I agree with them or not, I’m going to learn something from them. When I’m out talking to other people, regardless, I always try to learn from them. And then I also spend time when I’m teaching working on one thing for me while I’m teaching. Because I’m throwing an attack at this student for them to work on. I am making sure that attack is 100% perfect.

GW: Yeah. Demonstrations are really useful.

SF: My favourite people to teach are beginners.

GW: Oh God yes, me too.

SF: Because that means when I teach beginners, I am working on the fundamentals every single time and there is nothing complicated in a sword fight. It is only a string of simple things put together in different orders.

GW: Bingo. And advanced technique is just basic technique done really, really well.

SF: Yep.

GW: Do you know my rule of beginners? My rule of beginners is this: If you show it to them right a thousand times, they will eventually copy it correctly. You show it to them wrong once. They will copy it perfectly, first time. It’s true, isn’t it?

SF: There’s a great book I read that I would highly suggest to anybody watching this or listening to this, The Talent Code. It’s a guy in Alaska in the middle of winter wanted to figure out how does Tiger Woods dribble a golf ball on a golf club.

GW: Right.

SF: And so he did that and he got really interested in how the mind works and the neural circuitry and what creates. How do you learn something? And he went to a little music recording studio in Tennessee that has put out some of the most famous Country and Western singers. He went to this little tennis school in Russia that has tennis players in every Olympics and different things like this. What is similar in all of these places around the world that put the best of the best out in the world? And what he found: it is a constant review of the basics.

GW: Right.

SF: Always practise your skills on the piano first thing. Always practise a simple recovery with your tennis racket. Over and over.

GW: So for me, that is 99% of my practise, I would say, is footwork and point control.

SF: And mine is footwork and guards.

GW: Okay. There you go. Yeah. And, you know, oh, and incidentally, in case people think we disagree, I when I say footwork in my head, that includes guards and I spent quite a lot of time just standing in guard, thinking about being in guard, feeling what it’s like to be in guard. How can I make this guard better, and blah blah blah.

SF: So it’s like tutta porta di ferro. Opening the door.

GW: Yeah. Hold that door.

SF: If you touch the sword with your thumb, you manipulate a small muscle in the front of your shoulder, and it turns you inside and it affects your point. And if you don’t touch it, you open that shoulder up and it allows you greater mobility. And it’s these small things that makes you perfect because practise makes permanent. Perfect practice makes perfect.

GW: Perfect. Yes, that’s very true. Now I have a couple of questions that I ask all of my guests. I don’t know if you listen to the podcast, many of my guests do not listen to my podcast, and that’s perfectly OK. What is the best idea you haven’t acted on? Or do you act on every good idea to get?

SF: I act on almost every idea I get. Doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

GW: Fair enough.

SF: But. If I’m afraid to try something, I’ll never find things that I didn’t expect. So I’ll try just about anything. Either it’ll work or it won’t. If it works, great. If it didn’t, I learned something. So I try everything.

GW: Yeah, I have friends who are good at various things. And when they say Guy, do you want to come and try this thing? If I have the time in my schedule, I always say yes. Because, you know, that’s how I know what it’s like to scuba dive because I’ve done it once and it was awesome and I loved it. And it was this completely alien set of skills which involve, for example, breathing while your face is underwater. And that is not a normal thing to do. That is a weird thing to that. You shouldn’t do that, except of course, you have to screw it up.

SF: Right. I tried jumping out of a plane for the same reason.

GW: I can’t do that until my youngest child turns 18.

SF: It was a 50th birthday present from my bride.

GW: What is Sue trying to tell you?

SF: I think I have good life insurance. I’ll try anything.

GW: I don’t think my wife would buy me jumping out of an aeroplane. She’s a little bit worried about me letting to fly planes. One of the scariest things about flying planes is you have all sorts of drills and procedures you have to learn for when things go very badly wrong. Like, for example, you are taking off and your engine quits. What do you do? You have approximately 3 seconds before you stall. At that point, you’re so close to the ground, there’s no recovery from the stall, you are fucked. And it’s just a matter of luck whether you live or die. But if you drop the nose fast enough, you maintain flying speed and you have about 20 seconds to find someplace to put the plane down. It’s like, I don’t want to be in an aeroplane with an engine that can quit. No, make a better aeroplane. No. But actually my favourite thing to do in the plane so far is what’s called a glide approach, which is basically you are close to the airfield that you’re going to land at anyway and your engine quits when you’re maybe 2000 feet up and you have to kind of manoeuvre around in the glide and get your flaps sorted out and get everything sorted out. And effectively you do a normal landing because a normal landing is done basically gliding anyway, because you put the engine to idle, you pull the throttle to completely out when you’re maybe a hundred, 200 feet. Basically, when you’re sure you’re going to make the field, you cut the engine. And so every landing is done as a glide anyway. But instead of gliding from a couple of hundred feet up, you’re having to sort itself out and get your approach right and everything, with no engine. It is great. It is the kind of purest fly.

SF: It’s very much like parachuting.

GW: Yeah. I would love to jump out of an aeroplane with a parachute. But yeah, I’ve got at least five years to go.

SF: Everybody asked me, were you nervous? Were you scared? Well, I mean, it was fun, but I’ve been closer to death.

GW: Right. If your chute opens, you’re probably going to be fine. Did you jump with an instructor attached to you?

SF: I did. I did the tandem. They won’t let you do it alone for the first time.

GW: Okay. Because it is quite different if you if the chute deploys automatically. Or if you actually have to remember to pull it. One friend of mine went for this sort of training and then they jumped out of the aeroplane. He went with a friend and they jumped out of the aeroplane. And his mate was so spaced out and amazed by the whole thing, he didn’t pull his chute. And the instructor who was kind of skydiving with him was like, pull your fucking chute and do the things that they do to make it pull the chute. And he was like, oh this is so amazing, man, I’m flying, oh my god. And he pulled the chute just in time.

SF: Oh, good.

GW: But it was horrible for my friend because it was like.

SF: He’s watching his friend die.

GW: Because at this point, of course, his chute is already deployed and he’s looking down and he can see that the instructor is like skydiving down with the guy that will pull his chute if he has to, to save his own life because there’s nothing he can do to the guy who’s diving. He can’t pull his chute for him. But, um, yeah, he actually managed to kind of get through to the guy that he needed to pull his to fucking chute.

SF: When I went out, I was strapped to an instructor, but I pulled the chute.

GW: Super cool. Yeah. I’m looking forward to that when I get to do that.

SF: So, yeah. Going back to your question. Yeah, I try everything.

GW: Yeah. Okay. So there isn’t some niggling project you wish you’d had time for?

SF: I don’t think so. I mean, and some of the things I’ve tried have failed.

GW: Of course. If everything you try works, you’re clearly not trying enough things.

SF: Right? And there’s a difference between learning a skill and being lucky. And never underestimate the power of luck, but don’t rely on it. So try everything to learn what you do and don’t like.

GW: Yeah. Good advice. Okay, final question. Somebody offers you $1,000,000 or so to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide. How would you spend the money?

SF: I think I would support fledgling groups just a little bit here, a little bit there, and, you know, a couple practise weapons for the ones that can’t afford it. So they can get the tools to practise with because without the proper tools, you don’t get the full feeling of what you’re trying to do.

GW: Okay. Couple of things come to mind. Firstly, so you’re talking about setting up a fund that people can apply for to get help buying equipment. Is that it? What to you constitutes proper equipment? Let’s say just for longsword. Keep it simple. What in your head constitutes proper equipment?

SF: Well, I really don’t like feders.

GW: No, me neither. Horrible things.

SF: But that’s my choice. If there is a group that’s working specifically with those because they’re doing that style, I’m not to choose. But I think first and foremost, hands and heads. I think that’s the most important equipment.

GW: Masks, helmets and gauntlets.

SF: Yep. And then we can get a sword or two. I always buy in pairs. Because you’re going to want to show your friend and if you only have one, it doesn’t work. Because they cease to be your friend after you hit them a couple of times with the sword and they have nothing.

GW: Yeah. That’s good advice, actually, always buy swords in pairs. And in fact, obviously when I was in Finland in the salle, we had millions of swords. And there’s always plenty for everyone. Here, I sometimes find myself with a student or some friend or whatever, who wants to have a go at something. I don’t have training equipment for other people. I only have my own gear here. And yeah, I’ve got like five longswords here, but four of them are sharp.

SF: And again, they will cease to be your friend after that.

GW: Yeah, well, quite. Although I always give the sharp to my friend because that’s that fair. Because if they cut me, that’s my fault. But if I cut them, that is my fault too. So, yeah, it’s my fault either way. So they should have the sharp so that the only person likely to get cut is me. But yeah, so I have a blunt rapier and a blunt longsword. Both of them are in process of coming. Just so that I have my spares.

SF: You got to buy in pairs.

GW: Yeah. Okay. So, like equipping, so masks, gauntlets and a pair of swords. I mean, with a pair of masks, a pair of gauntlets and a pair of swords, there’s an awful lot of training you can get done.

SF: There is. And with $1,000,000, million pounds, you can help start a number of groups with the proper safety equipment.

GW: I would say maybe 500 groups, maybe $2,000 per group, something that that would be plenty.

SF: Easily. You could help a lot of different groups and this will spread the word more. “I study martial arts.” “Cool. Eastern or western?”

GW: Well, both, obviously. The world is round. If you go west far enough, you end up in the east.

SF: That’s right. And again, look outside of your industry. I focus on Italian and English martial arts. That’s my speciality. That does not mean I don’t study other arts.

GW: Sure. Yeah. Me too.

SF: My favourite thing is comparing notes with everybody.

GW: Yeah. I actually find it particularly useful comparing notes with, for example, traditional Japanese guys because the sort of 16th, 17th century Japanese weapons work is very close in many ways to what we’re doing.

SF: So is the early Chinese.

GW: I haven’t looked at that in any detail.

SF: With the Dao. You see a lot of similarities.

GW: Sure. Huh.

SF: Okay. And in fact, in the unarmed sense, you look at a lot of the Asian martial arts and where the hands sit, you put weapons in their hands and

GW: Suddenly they make more sense.

SF: Yes, they do.

GW: Yeah, because.

SF: Why would I punch somebody with my knuckles if I can get a steel or a bronze tool to hit them with?

GW: Or even a piece of wood? I mean, that’ll do the damage.

SF: The hand positions don’t make sense until you put weapons in it.

GW: Yeah. Yeah, I’ve seen that. Anyone who does proper, like, unarmed stuff, they always have their hands up. Covering the head, covering the face. Always. And sometimes they are leaning back a bit like 18th century pugilism and sometimes leaning forward. There is this huge variety, but as always, at least one hand at face level to keep your head protected. But you see these Asian martial arts that aren’t doing that. And yeah, as soon as you put a weapon in those hands, those hands make a lot more sense.

SF: When I teach or play with pugilism, when I’m right foot forward, I stand in rapier and dagger. But when I go left foot forward I go longsword.

GW: Of course. To me, that makes perfect sense. Well, you would. All righty. Well, thank you very much indeed for joining me today, Steaphen. It’s been great catching up with you.

SF: It’s always a pleasure to talk to you, my friend. It’s never enough. We need to do it more often.