GW: I’m here today with Joshua Wiest, who is an instructor at the Triangle Sword Guild, focussing on the fighting systems of masters Achilles Marozzo, Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Antonio Manciolino, and Camillo Palladini. That’s a lot of Italians. He’s also a successful tournament fencer and host of the historical martial arts podcast l’Arte dell Armi. So clearly something of an Italophile. Anyway, without further ado, Joshua, welcome to the show.

JW: Thanks for having me, Guy.

GW: Whereabouts are you?

JW: I am in Raleigh, North Carolina, in the United States.

GW: Really? I once got stuck in the airport there for about nine hours.

JW: Really? Why?

GW: I was living in Peru at the time, when I was a teenager. I forget if it was on the way to Peru or on the way back. But flights got cancelled and changed and moved around, and I ended up having to wait in Raleigh, North Carolina. Actually, Raleigh Durham is the airport, isn’t it?

JW: It is.

GW: Yeah, the only reason I know that is because I was in there for nine hours about 33 years ago.

JW: And cursing Raleigh Durham the entire time. It’s changed a lot and it’s a lot nicer now. It’s not just one terminal. They’ve built a new one and it’s beautiful.

GW: Ah well, they didn’t do that in time, not soon enough for me. I seem to remember sleeping on the floor. But let’s not be deterred by my one not-so-great experience of Raleigh. Is it a nice place to be?

JW: Yeah, it’s a great city and it’s stuck between an equal drive to the mountains and an equal drive to the ocean. So, you have convenience of basically exploring whatever you want to explore. If you’re kind of a beach person, you have the beach. And if you’re a mountain person, you can go hang out in the mountains. And the whole state is basically a deciduous rainforest. So it’s beautiful. A lot of trees.

GW: Lovely. OK. So are you from there?

JW: I am. My family is not originally from here. They’re from the Midwest. But I grew up here. I’ve lived here my entire life.

GW: OK, so how did you get started in historical martial arts? Is there a lot of that going on in North Carolina?

JW: Yeah. So it’s pretty funny. I’m an avid listener of your podcast and I feel like a common theme that I’ve heard from your guests is that they started writing a book and they never finished it, or something along those lines. I’m just going to add to your pile of authors that never quite fulfilled that ambition. I was writing a book, a historical fiction novel about Epaminondas, who’s a Boeotian general right after the Peloponnesian War. And I was writing this one scene in the book, and he had basically been relegated back to… he had been removed from the Boeotian government and was forced to reinvent himself in this city when they had just overthrown the Spartans. And I got to this scene where he’s working with Gorgidas to form the Sacred Band and they are training these guys to use weapons. And I was like, I have no idea how to use any of these weapons. And I was like, I need to rectify the situation. This is a problem.

GW: I couldn’t agree more.

JW: I’ve always been very passionate about history. It’s not what I do for my profession. I’m a medical laboratory scientist and I work in a hospital, but history has always been my driving force. And so I decided I needed to do something about it. So I started doing some research. I looked into just doing Olympic fencing or sport fencing, and I found a school. And then through that school, I found a group of historical martial artists. I found the Triangle Sword Guild and I actually started doing rapier first.

GW: OK, it’s a good place to start.

JW: It was, yeah, and it actually worked because my historical interest at the time, even though I was writing this book and doing a ton of research on the Corinthian war period of Greece, I was also at the same time reading Peter Wilson’s Thirty Years War book and which is a fantastic book. And so I was doing this deep dive on the Thirty Years War and reading about the 80 Years War and learning rapier at that time was perfect. So I got into that and then our rapier programme basically ground to a halt. And in its place, a new instructor came in and started teaching Bolognese and the rest is history, I just kind of stuck with it.

GW: OK, so you were learning rapier to get insight into ancient Greek warfare. Interesting.

JW: Let me clarify. At the time, at the time when I started, the way that TSG handles their beginner classes for two-handed sword, for longsword, which is what I was going to be doing, is they basically do blocks where they’ll open up beginner classes like every two months just because there is a lot of interest in the area. So to keep the beginner classes at a reasonable size that they can work with, they keep them in two-month blocks. So I was waiting for one of those blocks to open and I did start two-handed sword. And they actually created a class on a Thursday because I worked weekends at the hospital. So all the weekend classes I couldn’t take, but the weekday classes were what I was trying to fit into. And so I did do a little bit of KdF for a while, but then that class kind of fell through, one of our instructors that was teaching that class ended up having surgery. And so I really at that point, I was just sort of pigeonholed into the Bolognese system, which was fateful.

GW: Lots to unpack there, because actually thinking about it, with the Bolognese sources you do get shields, targes, bucklers, polearms. So it’s probably closer to being useful for doing your Peloponnesian War stuff than Kunst des Fechtens would be.

JW: Yeah, absolutely. As a matter of fact, the more I’ve gotten into the Bolognese system, the more I’ve heard, even from other practitioners that there are times where either Marozzo or Manciolino are basically cosplaying the Greeks with when they start using, like partisan and Rotella.

GW: Right. I have a copy of the 1568 Marozzo. I have the 1568, like the original.

JW: That’s awesome.

GW: Yeah, I could take it out and wave it to the camera, but the people listening can’t see it, so it’s not really fair. And it’s got some very strange arms and armour in there, in the pictures, it’s like, “Why on Earth?” You’re right. Yeah, they’re basically cosplaying the classical period.

JW: They are, and with especially with Manciolino in particular, he goes on these long like humanist diatribes where he’s just like he’s throwing out all of the knowledge that he’s gained. You think about the context of the time writing and probably starting sometime in the early 16th century. It’s the tail end of the Italian renaissance, and he’s really just kind of like flexing his literary muscles, just showing everybody that he’s this knowledgeable scholar of humanism. And it’s pretty funny. And it just feeds that narrative. It feeds the narrative that he’s just some of this stuff, we’re not really sure how practical it is, but he’s definitely cosplaying the Greeks.

GW: So for the non-specialist listener, when they think Bolognese, they’re going to think spaghetti and we get this all the time. So could you just explain to the to the layperson, what is this Bolognese system we’re talking about? Where does it come from? What is it about?

JW: Sure. The Bolognese system is basically something that we use to categorise a system of fighting because it uses common language. That’s the best way to put it. There are a lot of very intelligent people who really kind of postulate that there’s more of a northern Italian system and then the Bolognese system just exists within that framework. But the one thing that we have that unifies the Bolognese is a system that makes it easiest easier for us to understand is that we have these five principal treatises that use the same language for the names of their guards, their cuts, thrusts, et cetera. And that’s really what we categorise as the Bolognese system that exists for about 100 years, roughly, between really the entirety of the 16th century is where we were kind of looking with the Bolognese system.

GW: OK. And where does it come from?

JW: It comes from Bologna. Bologna, Italy.

GW: OK, but I mean. I’m hoping that even our lay people figured that much out. But yeah, it has antecedents with this Dardi or Bardi fellow.

JW: Yeah. So Filippo Dardi is widely considered the father of the Bolognese system. And then he has a prospective student, de Luca. Marozzo says of de Luca: “more brilliant swordsman came from de Luca than Greeks came from the belly of the Trojan horse,” is what Marozzo says about him.

GW: yeah, I hope somebody someday will hopefully say that about one of us one day. As instructors, that’s what you want, isn’t it?

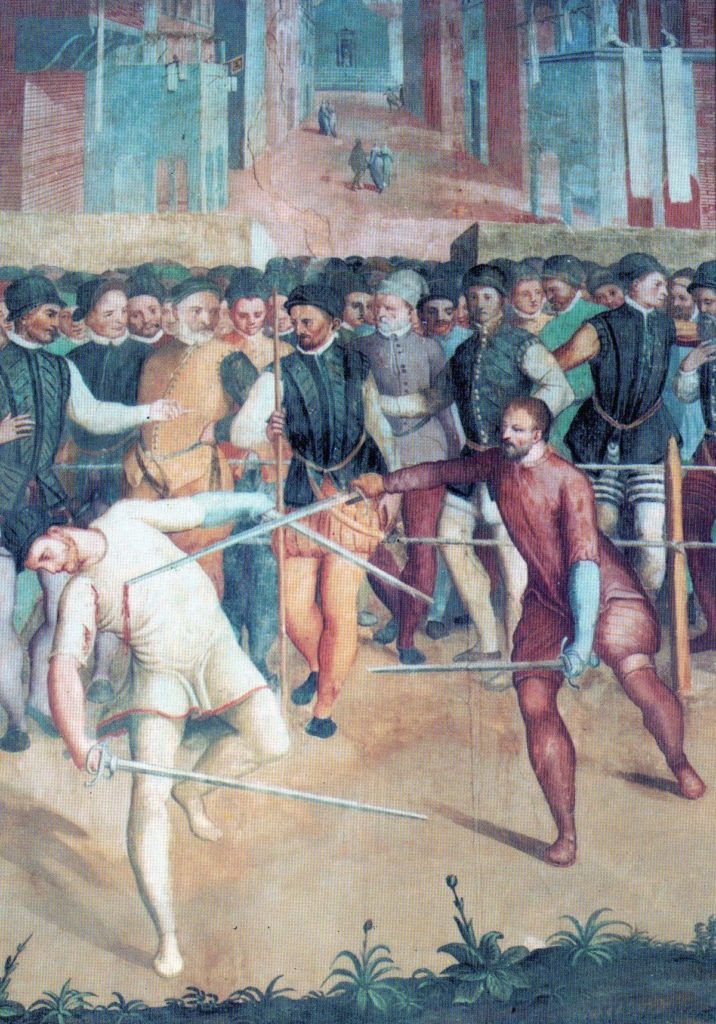

JW: Absolutely. Yeah, the Bolognese system, the cool thing about it is throughout this period, we have historical anecdotes, really because of the documentation of some of these fencing masters that we have these stories of fencers and Viggiani is a good source for that. But you know, a lot of times these guys will start name dropping. So, we’ve got, let’s see, we’ve got Giovanni de Medici, Giovanni de la Bande Nere, right? We have Guido Rangoni, who’s mentioned as a practitioner of the Bolognese system, he was a condottiere during the Italian wars. He’s the person that Marozzo dedicated his treatise to. And then we have more people like Francesco Maria della Rovere and Count Hugo.

GW: If you’re into the Italian 16th century, we’re talking about rock stars effectively.

JW: Yeah, absolutely.

GW: Fiore does the same thing. He claims, for example, Galeazzo da Mantova as one of his students and then goes on about how Galeazzo beat Boucicault in a duel and Boucicault being Marshall of France at the time. And so like top knight in Europe, if you like. So, so basically, what Marozzo is doing is pretty much the same. These people think I’m cool, therefore you should, too.

JW: Yeah. And that brings up an interesting point because you kind of wonder, and this is something that I thought a lot about. I feel like we get this prevalence of fencing treatises, or at least we see the development of systems after periods of long war. So with Fiore, for example, he’s almost a contemporary of the great captains. Well, he is a contemporary of the great captains in the age of, you know, you have John Hawkwood and you have the Golden Company and you have the White Company running around in Italy. And then and then you get Fiore and you have the development of this system. And we see this system developed and spread out throughout Europe. Well, not Europe, but Italy. I guess a little bit into Germany, but with the Bolognese system we see the writings really kind of start in about the 1520s. We don’t really know when the Anonimo Bolognese was written, but we know that with at least from Manciolino and Marozzo, we can date those into the 1530s for their publication. And they come at the heels of the Italian Wars. We have this flowering of these ideas that really come and are born of conflict.

GW: OK. So, if I remember rightly, I think Manciolino’s book came out 1531, wasn’t it? And he’s the first of the printed Italian sources, correct?

JW: Yeah.

GW: OK. Yeah. I actually was in an Italian bookshop about six years ago in Verona, and they had Manciolino. But it’s worse. It’s worse than that, right? I went in and in Italian, I asked them if they had any fencing treatises. And they said, no, we don’t. And so I gave them my card and said if you find any, if you come across any, let me know. Right? And later that night at dinner, my wife and I are having dinner in a restaurant in Verona, just on the streets because it’s summer and it’s nice. And this guy from the bookshop comes up and he was super polite. He called me “Maestro Windsor” because he looked me up. Because he wasn’t actually there when I was in the shop, his assistant was there. He said, “We have a Manciolino. Are you here on Monday?” I said, no. We’ve gone home by then. So I didn’t see it. And honestly, they were asking significantly more money than I had available for it. So I was never going to buy it anyway. But yes, I could at least have handled it.

JW: There’s actually a Manciolino for purchase right now, and they’re asking for $7000.

GW: Where is it?

JW: I found it on Good Reads. It’s through an auction website. Yeah.

GW: OK. $7000.

JW: Seven thousand. Mm hmm. I know. I know.

GW: Oh, it would go so nicely with my Marozzo and my Fabris.

JW: It would. Yes. I’m sorry.

GW: Oh God, OK. Yeah, yeah, let me have a little think about that. I have two kidneys.

JW: Yeah, exactly. So when I was when I was on my podcast, when I was talking to Michael Chidester, I was really pressing Michael. I was like, listen, we need a facsimile of Marozzo. And he was like, look, if you can, if you can find a facsimile of Marozzo that has margin notes, I will consider it. And so he’s tasked the greater HEMA community to go out and find a Marozzo with margin notes. Sort of like what he’s doing with the Joachim Meyer right now. And in the process, he was talking about potentially doing a copy of Manciolino instead because he likes Manciolino, because it’s tiny.

GW: Yeah, it’s a tiny little book.

JW: I think it’s kind of cool. I think it’s great. It’s a pocket book.

GW: It’s six inches by four or something. It’s really small.

JW: Yeah, which is it’s cool because he even has like really condensed advice that’s just like, really great stuff.

GW: Hang on. You want a facsimile of Marozzo? Does it matter which edition?

JW: No.

GW: OK. Well, I have high resolution photographs of not the first edition, but my edition, which is the 1568 and Malcom Fair’s copy of the 1540, the undated one. Producing a facsimile from those is not difficult.

JW: Let’s do it.

GW: OK. Honestly, I don’t think the average listener will be terribly interested in the nitty gritty of us discussing exactly how we would proceed with that.

JW: We’ll have to talk about that some other time.

GW: Maybe we’ll chat about after we’ve done recording. But in all seriousness, the data is there. The process is just clean up the images, arrange them into a print file, add an “about this book” page at the end. If you tell me there’s a market for it, I could just get it done.

JW: Yeah, absolutely. Well, through my years of study. I’ve really come to the solid conclusion that if you’re not reading a translation and comparing it to the native language, the native Italian and then comparing it again to the actual text itself, then you’re going to miss things because there’s certain things that just are absolutely essential to really kind of understand. Like if you run into something that’s hard to understand, a lot of times you have to start referencing the other source material and kind of build that out.

GW: My view is that if you’re getting paid for your opinion, it should be based on the original. It’s not reasonable to expect amateurs in a club who happen to be teaching because they happen to be the most senior person present or the most experienced. And it’s not their job, it’s just something they do at the weekends and what have you. It’s perfectly all right in that situation to be basing your interpretation on translations, right? Because learning the language is hard and it takes a long time and it’s a tedious process. And personally, I suck at it. But the reason I don’t teach any German swordsmanship other than 1.33 is that I don’t read German well enough or at all in fact, to base my interpretation on. 1.33 is a dodgy one, because I am dependent on translation, but I have like six years of Latin at school or five years of Latin at school. So I have just enough Latin that I can go in and have a little dig. But that’s an edge case I probably shouldn’t really be teaching 1.33 based on my own principle of you should be able to read the original language. Yeah, but yes, I do like Fiore in California and some English sources and some French sources because I can read those. But I don’t do the German stuff because I can’t read German. Because this is my job. I feel if I’m teaching a Liechtenauer seminar, I ought to be able to read the original language and I can’t, so I don’t.

JW: Yeah. I just got done teaching, going on a deep dive in a study of Andre Lignitzer. And I had to rely on the German speakers in our club, and the people who could basically go in and take a look at the middle high German and compare it to the translations that were available, there’s some absolutely fantastic translations. But it was actually really beneficial to go back in and look at the language because like with Lignitzer in particular, he’s got these situations where sometimes he’ll use plurals for things instead of a singular. When he’s talking about shields. Andin the German system, a lot of times they’ll refer to the lower half of the sword as the shield. And so he’ll say something along the lines of, durchwechsel underneath their Schilts, right? And he puts an “s” on there. But sometimes that gets lost in translation. You’d be surprised how many translations there are of Lignitzer where they forget that “s”. And so they just say durchwechsel under the shield instead of the shields, which changes the play significantly. Just a little anecdote.

GW: I’ve only published one translation and that was of Vadi. My first stab at it was shockingly bad. Fortunately, it got picked up and I did a second crack, which was much, much better, right? But it’s astonishingly hard to do it well and you are always making these sorts of decisions about, OK, we could translate it like this or like that, and there’s nothing in this source to make it one way or the other. And so you’re still always making these judgement calls. And that’s the problem. Languages aren’t ciphers of each other; they are different ways of seeing the world.

JW: And that’s why you just need somebody who has that context that can help inform you. I don’t know, I got your 1.33 class here. I signed up for it.

GW: The online course?

JW: I did. So one of the one of my pursuits that came out of the pandemic was I started teaching Sword and Buckler, almost like an exclusive sword and buckler class. So in the framework of that class, one of the things that I’m doing is teaching from all the sources. So we run in 40-week cycles. So we’ll do 40 weeks of Manciolino sword and buckler, and then we’ll do 40 weeks of 1.33 and Lignitzer and Talhoffer because Talhoffer is really simple.

GW: He’s got like three buckler plays.

JW: Yeah. And then he actually mentions that he’s read a treatise with a priest teaching these plays in Latin.

GW: Does he say that? I wasn’t aware. My god, I need to reread Talhoffer. It’s been 20 years since I looked at that.

JW: So in a couple of the different manuals that he’s put out, he mentions. So, in two of them, I think in like the Württemberg and then his personal manuscript, I don’t know what the name of that one is. I just remember on Wiktenauer, it’s named his personal manuscript. So that’s what I go by. If it’s good enough for Michael, it’s good enough for me.

GW: We’ll stick links in the show notes so people can find them.

JW: In those two treatises he actually has sword and buckler plays, and he gives you about six roughly in this continuation, and some of them are kind of obscure. But then in his other treatises, he just has that namedrop of having seen something with a priest with sword and buckler. And he says that he understands it. That’s all he says. It’s just like one picture. And this block of text that says, I’ve seen this and I understand it, and that’s it. So I don’t know.

GW: It took me a while to get to grips with 1.33. I think I worked on it for about six months before I taught a class on it. But it’s not a complicated system.

JW: It’s not. But it’s brilliant.

GW: Absolutely. And it has so much in common with all the other systems.

JW: Yeah. When I was reading about your approach to it and I realised that we were following similar veins in terms of how we were understanding the approach of 1.33, and then I was like, OK, this is perfect because as much as I would love to dedicate a ton of time to really kind of developing my own system and understanding of 1.33, sometimes when you’re focussed in other areas, you can continue to focus in those areas and rely on the hard work of other people.

GW: Absolutely. I have a pretty solid grasp of the Liechtenauer material because friends and colleagues have taught me their grasp of it and. It’s never going to be perfect, of course it’s not. But then if I did it myself, it wouldn’t be perfect either. But it’s enough that it kind of informs and develops your understanding of your own specialisation, and you don’t end up getting siloed into this pathetically small little, “I only do Italian longsword.” But yeah, this is normal academic work. But you’re a scientist, right? And the scientific stuff that you do is probably drawn from a lot of other people’s work, I don’t suppose you invented all the different reagents and tests and things that you do, did you?

JW: I wish. But I didn’t.

GW: So yes. Using other people’s work is how we develop at a reasonable pace. If you have to invent everything from scratch, you’re going to be stuck in the Stone Age for a very long time.

JW: Exactly. Yeah, I agree.

GW: All right. Well, when you’ve done the course, I’ll be interested to hear what you think of it. And you can be frank.

JW: I will be honest, I promise.

GW: OK, so all right, we mentioned Vadi a couple of times. Just for people who may not be familiar, Vadi wrote a treatise in around 1480s for the Duke of Urbino, and it has a lot of commonalities with Fiore and may have some commonalities with some of the Bolognese stuff and it is knightly combat. It’s a manuscript, so it’s not a printed source. There’s only one copy of every know of which is in the Biblioteca Nazionale di Roma. So the National Library of Rome. I’m pretty sure you’re familiar with Vadi because as an Italophile you pretty much have to be. But what do you think the relationship between Vadi and the other sources?

JW: About a year and a half ago, I got really frustrated with Marozzo’s two-handed sword.

GW: I can understand that. I’ve looked at it. He’s not very clear.

JW: Yeah, and I started to kind of get this feeling that Marozzo in the way that he teaches the two-handed sword, I wasn’t quite sure about the martiality of his approach. So oftentimes the Bolognese masters or writers will identify the things that they think should be done in the salle and the things that they think would be done with sharp swords in earnest. And so I wasn’t quite sure how much of a in earnest approach Marozzo was providing, and not that the depreciates what he’s teaching by any means, but it was more of trying to understand whether or not it was. And I’ve heard about this about Vadi too where Vadi’s basically writing this bleak, forlorn love letter to the two-handed sword as it’s fading out and its relevance and is basically just kind of like, we don’t know if he actually used it. And I kind of got a similar feeling about Marozzo, and I wasn’t quite sure. So I decided to really start looking into it and to do that, I needed to do two things. And that was study Fiore and study Vadi. And so I started studying Fiore, and I’m actually working through Fiore right now. Again, co-opting ideas from other people. You know, we have an instructor in our school, Kurt Holtfreter,

GW: I know Kurt, he’s had some private lessons with me.

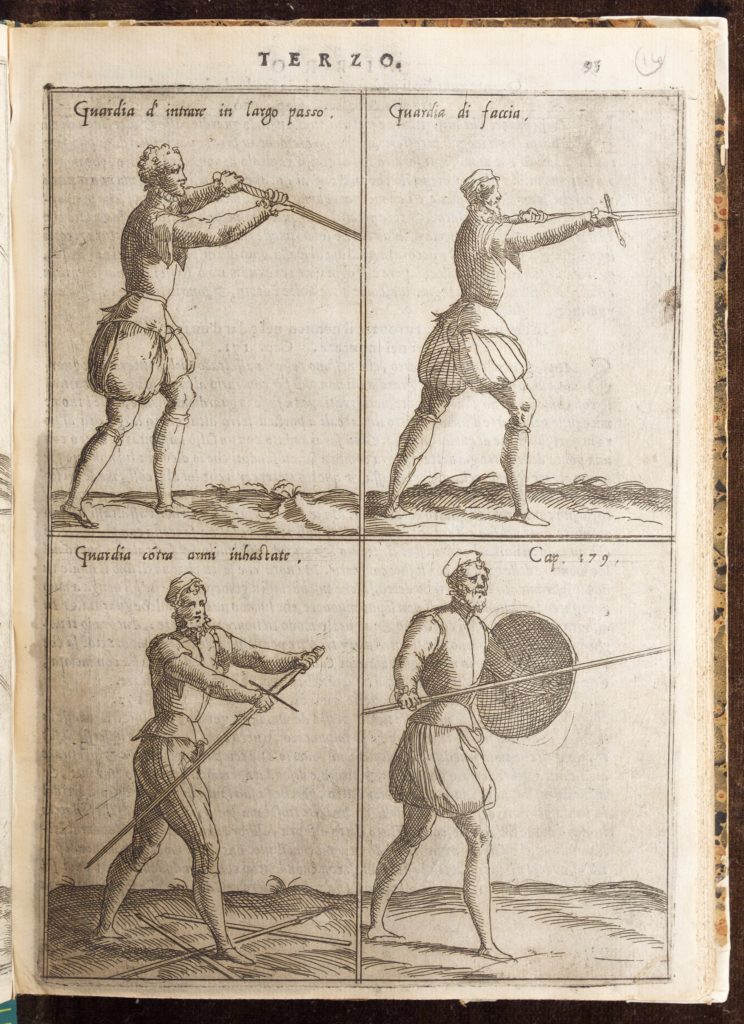

JW: Yeah. And he’s a fantastic fencer, but he’s gone on this quest to really kind of understand and implement Fiore. And I’ve been working with him and it’s been fantastic because I’m starting to see all these like little similarities, these things that provide these distant echoes of aspects of things where I’m like, “Could that be, you know?” And that’s the scientific process, right? You start asking questions and you start wondering things and you start exploring, going down all these little rabbit holes to see if there’s any validity to what it is that you think. And that’s really kind of what I’ve been doing. Like just Marozzo called guardia d’intrare,[31:27] where he’s up in, for German people, it would be up and left Flug. Or you could say he would be in fenestra for the Fiore folks.

GW: Ooh, I’m not sure guardia d’intrare is fenestra.

JW: No, no, no, it’s not fenestra.

GW: It’s definitely not fenestra.

JW: And I’m talking in terms of just like what the guard looks like, right, in terms of like the posture.

GW: And I’m teasing you a little bit.

JW: So but here’s the thing, this is the rabbit trail that I went down is guardia d’intrare, guardia d’intrare because Marozzo is basically trying to convey colpo di villano [32:07].

GW: Why?

JW: Because he’s basically doing a hanging parry where he’s coming up underneath and then he has a narrow stance, which is where you’re just bringing your sword up. And if you look at the angle, he’s got his sword all the way down and then he’s stepping out with his back foot and then he’s stepping in and closing.

GW: OK, one second, I’m just going to dig out my Marozzo and I’m going to have a look for myself and I’ll stick a photograph in the show notes for the listeners. OK, guardia d’intrare. This is my 1568. So it looks like you to get to have a look at it. It’s nice, isn’t it? I think it needs re-binding. It’s got 19th century binding on it, but the print’s original and in pretty good nick. We have guardia d’intrare non in largo passo, and guardia d’intrare in largo passo. Which one are you referring to?

JW: So I’m wondering if that’s a continuation. Right? So basically, the way that he uses guardia d’intrare, usually going to be a way of parrying. So you’re getting up underneath somebody’s sword. And the idea would be that you’re entering because you’re getting around to their outside line.

GW: Oh, that’s an interesting idea. Let me just describe it for the listeners. So imagine if you’re both right-handed and you both come from the right-hand side and the swords are crossed and your opponent is pushing your weapon quite strongly towards your right side. If you lift your hands and let the point drop, their sword flies off to the side and you get effectively a variation on Fiore’s colpo di villano as you said. So you’re seeing it not as a guard, but more as a way point.

JW: Exactly. Yeah. So the reason is the guard of entering is if you can get to somebody’s outside line and you’re pressing the advantage, then you’re always going to have the availability to control because when you close the stretta from that place, you have all sorts of things that you can do. From that outside line, you can push a thrust, you can go for a grapple, but it’s a good way, it’s a safe way of entering because then you can turn their body too. You’re starting to turn their hips away from you and then you’re closing in on them. So you’re kind of refocusing.

GW: That’s interesting. OK. So bringing that back to Vadi, what do you think the connection is?

JW: The reason why I think that Marozzo is, I think Marozzo is co-opting ideas. I don’t know how genuine he is and his development of this system or if this is him co-opting ideas. Now, it kind of has to go back a little bit to a story about Marozzo. So like when we talked earlier, we’re talking about Guido Rangoni, and Marozzo in particular. He dedicates his treatise to Guido Rangoni. But Guido Rangoni was not the Lord of Bologna at the time when Marozzo was writing. So why would he write to Guido Rangoni? Because he probably had a personal relationship with Guido Rangoni because of the d’Estes at that time, when Marozzo was writing had basically been given power from the Pope to be in charge of Bologna, the Rangoni family had been removed from power in Bologna. And so the fact that he’s writing to the son of a noble who’s been removed from power in the city of which he’s writing is pretty curious, right?

GW: That is very curious.

JW: But it kind of leads you to the understanding that there might be more to this story. And so again, the idea that these things are generally born of war, Guido Rangoni was a condottiero and Marozzo calls himself a master of arms, and this is all speculative. There’s nothing to prove any of this, but I would love to prove it. But that would be like PhD level research, and I wish I had time to do it. But with Guido Rangoni in particular, we know that he was pretty active in the Italian wars. There’s actually Christopher Hare’s book The Romance of the Medici Warrior. It has this really awesome story, which is a book about Giovanni Delle Bande Nere where Giovanni Delle Bande Nere’s Black Bands ended up basically having to work alongside Guido Rangoni when Guido Rangoni was given the charge of protecting Italy right before the sack of Rome. So you have this, this German mercenary army that’s coming down that are unpaid and just literally wreaking havoc and wrecking all of Italy. And so Guido Rangoni is given command to try to stop this attacking force. And Giovanni Delle Bande Nere is basically acting as his forward scout and harassing the Germans as they’re coming down. But either way, it documents that Giovanni Delle Bande Nere wrote a letter to a friend of his and basically he just smack talks Guido Rangoni the entire time for having these really undisciplined troops who didn’t know what they were doing. They said they were fat and lazy and like that that they were just awful. And I thought that was great. But to bring this all back to Vadi is that I think my estimation is that Marozzo probably was associated with Guido Ragoni in some way, and that’s where he got a lot of these ideas. And I think he’s co-opting ideas where, if you look at his two-handed sword, he’s even co-opting ideas from Pietro Monte. He basically does things that are the Levata, right? Like if you look at his second assault of the two-handed sword, he starts out by doing the Levata. He says that you cut a falso dritto and then a falso manco. In my mind, that’s what he’s doing. And I know that other people have theories and we’ve got this debate going on in the Bolognese community about what that actually is. But I think he’s showing the Levata and I think he’s co-opting ideas. I think he’s pulling all these things together

GW: For the one or two people listening who have not read Pietro Monte and memorised every word. There’s only going to be a couple of them. What is the Levata?

JW: So the Levata is basically where you throw a rising false edge cut. And so you kind of flick your hands over and snap the false edge of the sword at somebody hands. So you throw these rising cuts and then snap the sword at their hands and you turn on the other side and you flick and snap the sword at their hands.

GW: So that’s basically it’s a false rising cut from the right, followed by one from the left and Pietro Monte calls that combination a levata.

JW: Yeah. Well, so that action a levata. So he does levata from both sides.

GW: OK, so either one of those would be a levata.

JW: Yeah. So it starts true edge and then it turns over to false edge. And so it’s in that snap that you get that percussive action and that heavy rotation. And that’s basically what Marozzo is doing. That’s how he exits his plays. He does a levata to the hands. And I think that that’s really kind of how he proceeds to play in the second assault. I see him co-opting a lot of ideas. And I think that he is co-opting ideas from Vadi. I think we see a lot of similar structures in the way that he’s developing his guards. And then the tactical approach is relatively similar and that’s really what I’m trying to explore. And that’s kind of the path that I’m on. So working from Fiore now, probably in a year or so, I’ll start getting into this real deep dive of Vadi following Connor Kemp-Cowell’s awesome book that he just put out on Vadi, where he’s worked and done a lot of research on Vadi and the similarities of Vadi and countering Monte and how there’s a connection between those two. And so I’ll really start getting into a deep dive on that.

GW: OK, that came out just this year, didn’t it? I haven’t read it yet.

JW: Yeah. The Light of Mars.

GW: Yeah. So you would think that Marozzo would have seen a copy of Vadi’s book.

JW: I don’t know.

GW: Because there’s only one copy of it’s not. It’s not like everyone’s read The Da Vinci Code or seen a copy of it because it’s bloody everywhere. There’s like one known copy, and it would have been probably… Was it in the Urbino Library at that point? No, it would have been nicked by Borgia.

JW: Cesare?

GW: Yes, that’s right.

JW: Awesome. I love history. Yes, got a copy.

GW: Oh, good. OK. For people who didn’t see that, I’m checking my own Vadi book because I’ve written up a lot of this stuff in here and if it was better organised… Where is it?

JW: Yeah. You wrote a great essay about the similarities of Fiore and Vadi and Marozzo and the guards and everything like that. And I think that’s really helped to pique my curiosity in kind of looking through these things, you know?

GW: Yeah, well, I’m glad you liked it. And one of the reasons I’m asking about is, of course, I have my opinion. But I don’t think it’s likely that because again, there would have been one manuscript. It would have been in Cesare Borgia’s library. It’s unlikely the Marozzo would have had access to that, as far as I can tell. Borgia was dead by this point, anyway. And so where was that book? Honestly, I can’t remember. I can look it up. But if there was a kind of a vernacular of sword language and sword style. Like if you look at lineages in sport fencing now, they’re all using the same terminology, they are all coming from a common source. But the way sabre is taught in Hungary is quite different to the way it’s taught in Britain is different to the way it’s taught in America which is different to the way it’s taught in France and so on. So are we looking at a common system of which Marozzo would be a later dialect? What do you think?

JW: Yes. And I think that’s more of what it kind of comes down to. Obviously would Vadi have had availability, he probably did have some exposure to Fiore, right? In some way, because he co-ops a lot of his ideas from Fiore.

GW: Yeah, and he quotes him outright in some places. But then hang on, hang on. Just because my mum sang Twinkle Little Star to me and your mum sang Twinkle Little Star to you, it doesn’t mean that we’re related. There’s this common song that mothers sing to children.

JW: So, because the d’Este family and the Duke of Ferrara were for the most part in control of Bologna at the time when Marozzo was developing his salle and became the principal fencing instructor in Bologna. I don’t know if he ever saw a copy of Fiore. We’ll never know.

GW: But the copy would probably not have been in Bologna.

JW: No, definitely not.

GW: The d’Este Library would have been in Ferrara.

JW: Well, but there’s nothing to say that he wouldn’t have gone there. So, it’s a ton of speculation and ideas, but looking to themes and ideas that transcend and is Marozzo in some way, looking back and even looking at what was a common fencing system, sort of like what you said, like a common fencing system that existed in Italy. And is this something that was more prevalent than we really realised? Were there students of Fiore that were like De Luca and had more students than Greeks that came out of the Trojan horse? It’s possible that these ideas disseminated in and transcended. And then you have Marozzo, who’s basically taking these same ideas and providing the language of the Bolognese system, which is unique at its time and basically changing the language to match the things that he already understood as a common system.

GW: Yeah, possibly. And it strikes me that we are always dealing with a very restricted dataset because most fencing masters in the period did not write books. Right? And the ones who did write books, there’s no process by which only the good ones are allowed to write books. And there’s no fact-checking, so they can say whatever they want. And they can absolutely traduce somebody else’s system, or they can talk shit about other things as they do. If I’m remembering rightly, Alfieri refers to Capoferro as “Capo di ferro”. Which for non-Italian listeners would be Capoferro’s name means “iron head”, but “Capo di Ferro” means “head of iron” – thick. That was deliberate. That was Alfieri being a dick.

JW: Well, we think that Manciolino was talking smack about Marozzo in his book because they might have had some relationship. Again, this is all very speculative.

GW: But Manciolino predates Marozzo.

JW: He does, but they were both writing at the same time. There’s a possibility that and Michael Chidester actually just said something about this recently that there might be… Or maybe this is something that Matt Gallis researched, but there might actually be a copy of Marozzo that was originally published, I think, in 1525.

GW: Oh really, yes, that would be very interesting.

JW: They found woodcuts and the date is different. It’s not dated in the 1530s, and the problem is that they only found the title page, so they found the woodcut with a title page and the date is earlier than what we know.

GW: Oh, wow. That is very interesting. OK. Think of Thibault, right? Thibault’s fabulous book, The Academy of the Sword. The date on the title page is wrong, because the book was four years late coming out. So I think it’s 1628 on the thing, but it was actually only published in 1632, something like that. I’m probably mangling the dates, but finding a plate saying 1525, it could just be that Marozzo was a very slow writer and overshot by about 13 years or something.

JW: Given how laboured Marozzo’s writing is, it seems highly likely.

GW: It does, doesn’t it?

JW: Yeah.

GW: Or there is a book missing, but if it has got plates that doesn’t necessarily mean that it was a printed book because there is one copy of Capoferro that Roberto Gotti has, and bless him, Roberto Gotti is the man I got my copy of Fabris from. But he has a copy of Capoferro, which has the plates printed onto the pages, but all of the text is handwritten. I need to get myself to Brescia and have a proper look at that and figure out whether it is a presentation copy or whether it is the copy that got sent to the printers so they could set all the type. So it’s like the original original. Did Capoferro write it himself? There’s lots and lots of questions there. And imagine if there’s a Marozzo like that. A manuscript Marozzo with the woodcut plates from the first edition, or even earlier.

JW: So, yeah, the general speculation, to kind of go back to that, is Marozzo talks a lot about money in his treatise, he’s writing it for his son, he’s writing it for Sebastien.

GW: Eight Bolognese pounds to learn the Zogho Largo, something like that.

JW: Yeah, something like that. And it comes out to like $100 a month, a hundred U.S. dollars. But then Manciolino talks a lot about how you should disparage people who do nothing but talk about money when it comes to fencing. So whether or not that’s true. It’s fun to think about and it’s funny because it’s fun to rag on Marozzo. It’s fun to give him a hard time.

GW: Yeah, that is fair. OK. I have to ask. My absolute favourite 16th century Italian fencing treatise without question is Viggiani’s Lo Schermo. To me it’s like a Rosetta stone of how Italian fencing works. So for people listening, it was written in about 1551, 1552. It was not published until many years after the Viggiani’s death. It was published 1575, so it was about 25 years old when it was published. And it’s in the form of a conversation between these three characters. OK, so. What are your thoughts on Viggiani?

JW: Yeah. First of all, I agree. It is the Rosetta stone of most Italian fencing and I think it should be required reading for everybody who fences, because his discussion of tempo and association with Aristotle is one of the most important things to understand if you want to understand European martial arts. Hands down, because you have these two camps of people, you have camps of people who think that, I guess isolationists, if you will, or people who take it more from a nationalistic perspective or they’re like, no Italian fencing was always different than German fencing, and they never co-opted any ideas. And you have people who were like, oh no, there’s no way. If you look at the continuation of history through Italy, there are always Germans and Spaniards and French in Italy. So of course, they were borrowing ideas. But if you really want to find something that unifies all European martial arts, it is Aristotle and Aristotle’s physics. So Viggiani gives the best breakdown of that in his discussion of tempo. And you can literally take his discussion and you can apply it to Liechtenauer. You can apply to the Bolognese system. You can apply it to rapier. You could push it in everything that you can possibly imagine. You can even push it into 1.33.

GW: Yeah, of course. Absolutely. OK, let me just do that for you. The very first words: Fencing is the ordering of blows. And then he gives you these seven guards. So obviously he’s referring to blows. But he shows you the guards because the guards are the beginning, the middle and the end of the blow. And he says all fencing actions end in langort, which is the seventh ward with the weapon extended. So he’s saying, OK, you start from these various different positions, like under the under the left arm or on the right shoulder or whatever, and you go into this long position and those are the blows. That’s what that page means. Yeah, that’s Aristotle as understood by Viggiani. Viggiani explains Aristotle’s physics in terms as they apply to fencing tempo. That’s exactly what he says.

JW: Yeah. And so for people who aren’t familiar with the text or what he’s kind of going for, the way that he basically describes it, Aristotle says that time is the space in between two positions of rest. So if you’re in a position of something travelling, so imagine like the Earth in orbit, right? We consider something a year when the Earth has completed its orbit around the Sun. And that’s one year. So that space, if you were to imagine that imaginary line, is the continuation of that space. So that’s time. And so basically, what Viggiani is breaking down is he breaks this down into fencing terms, where tempo or time is the space in between two positions of rest. So if you’re in a high guard and you cut to langort, for example, so you cut to a centre guard, that space that the sword had to travel is the time. That’s the tempo. And it’s something that even in in 3227a, he mentions that Liechtenauer was aware of Aristotle. I can’t remember the quote off the top of my head.

GW: Shame on you Joshua, have you not memorized the whole of 3227a?

JW: Yeah, I think I pushed it out of my head. But yeah, so you have these things that just show up continuously throughout. And it’s brilliant. It’s a brilliant exposition of what this is, but to kind of take a step back with Viggiani in particular, and the reason why I really love Viggiani. Somebody had asked me to put together a lecture for what the approach to fighting was in the Bolognese system. And so I was like, OK, yeah, I can do that. And so I started looking at the sources and really how they approached the fight, like from the start of the fight. And at the time, I was really starting to get into Palladini because I had just gotten my copy of Palladini. And Palladini gives a great exposition of how the fight should start, where he says, basically you should, come up to your opponent, and once you’re two steps away, you should start watching your opponent to see what position they’re in. So that way you can come to the devices for how to basically foil their plans. And then once you’ve made a plan, he tells you that you should press your plan with abandon, essentially. Which is interesting advice, right? And I kind of wanted to unpack that a little bit. So I used that as the framework to really kind of build out the approach to fencing that I was looking at. I started looking at all the sources and finding a lot of agreement between all the different masters with this, whether it’s Manciolino, Marozzo, Viggiani, or the Anonimo Bolognese. They basically all say kind of the same thing, to constantly change your guard. And I was thinking, OK, well, that’s interesting. You don’t see people do that a lot where whether they’re constantly changing their guard, but sometimes we develop bad habits in HEMA that don’t necessarily fit the historical precedent.

GW: One thing that drives me completely batshit crazy is when you see two people who are supposed to be fencing each other with longswords on the outside measure going from guard to guard, poncing around instead of getting in there and hitting their opponent. It drives me absolutely insane.

JW: Well, which is funny because that’s kind of what they tell you to do. But there’s a level of intent for what they want you to do when you’re assuming your cards. And that’s what I was trying to figure out. What is it that they’re trying to convey where they’re telling you to constantly change your guard? And why are they doing that? And so much of it is to disguise your intention as you’re coming in. But there’s obviously some and this is something that in the Bolognese system, there’s a lot of emphasis on guards because there are a lot of guards. You know, Marozzo gives us 26 guards.

GW: That’s a lot of guards.

JW: It is a lot of guards, too much. You needed an editor so bad. But the idea is that there is a lot of emphasis on guards in these positions, and I started to realise that there’s a tactical framework that exists within these things. And at the time, I was still kind of holding the belief that Viggiani was kind of a heretic because Viggiani goes on this spiel where he’s like, the Bolognese guards, they have stupid names. I’m going to give them more practical names. And this is basically me reinventing the system.

GW: He’s not a heretic. He’s a critic.

JW: He is a critic. But he’s also a brilliant conveyor of ideas. And this is where this kind of came in. Because Viggiani was working with the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, he was tied to in some way to Charles V, and then eventually published his manuscript posthumously. His brother publishes his treatise for Maximilian II. And so we’re talking about him writing his treatise for the Holy Roman Emperor, which that’s a pretty big deal. If I start writing a fencing treatise for the President of the United States, I’ve probably done pretty good things, I’ve made a name for myself.

GW: The whole thing about book dedications is worth going into it because these days, you can dedicate your book to whoever you like, and it’s just a dedication. Back then, if you dedicated your book to a person, you pretty much had to get their permission for it. Fabris dedicated his book to King Christian IV of Denmark. And there’s a picture of the king on the front of the book. I will take it out and show it to you because I happen to have it.

JW: Oh, to be in your library.

GW: Any time you’re in Ipswich, seriously, I’ll sit you in an armchair and give you a Marozzo and a glass of wine and you’ll be fine. Yeah. Christian IV. There’s a picture of the man. If you put a picture of the king in the front of your book, giving the impression that he’s approved it, and he hasn’t. You are going to spend the rest of your life in a really nasty, smelly dungeon. And all of your books will be burned. And if he really doesn’t like you, he’ll probably burn you with them. So for non-specialist listeners, it is probably worth making that point that Viggiani can’t just stick the king’s name on the front, or the emperor’s name on the front of his book and expect to get away with it.

JW: Yeah, there was some tie there, but the cool thing about it is when you think about it in that context, Viggiani is explaining the Bolognese a system to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor. And he’s not writing to a knowledgeable audience. If I’m trying to convey an idea to a group of people and I need to basically translate things. They’re not going to have the same natural feelings towards the names of the guards where they’re going to have a sense of familiarity or a sense of understanding, or maybe even the cultural context to understand why coda longa stretta means the guard of the long tail. And then you get this thing from I think it’s the Anonimo where he talks about why it’s “coda longa stretta”.

GW: It’s Viggiani.

JW: Oh yeah, no, you’re right. It is Viggiani.

GW: Yeah. It’s like an important person has a whole retinue that follows them around.

JW: Yeah, exactly. And so you get this this description of what this guard is. And of course, he explains it here, which, jumbling that around. But the idea is that he’s actually changing the names of the guards to convey the ideas, the tactical implications of each of the guards. And it is the most brilliant exposition that I have ever read.

GW: It’s perfect. It is because it’s absolutely logical, right? If your guard has a point for it, it is perfect. If it doesn’t have the point forward, it is imperfect. But if it is chambered to strike, it’s offensive.

JW: If it’s low, it’s defensive.

GW: Right, right. So when he gives you the name of the guard, it’s like first guard. Let me get it out. I have the excellent, Oh, what’s his name?

JW: Jherek Swanger.

GW: Jherek Swanger. Yeah, I have his translation here somewhere. Probably better to read from. His Agrippa is there, his Di Grassi is there. His Marozzo is there. Where the hell is his Viggiani?

JW: He is prolific.

GW: I have recently moved everything around and I haven’t actually all reorganised the books.

JW: I think he starts with guardia offensiva perfetta.

GW: His first ward is up above the shoulder. No, his first ward is down here.

JW: It’s sheathed.

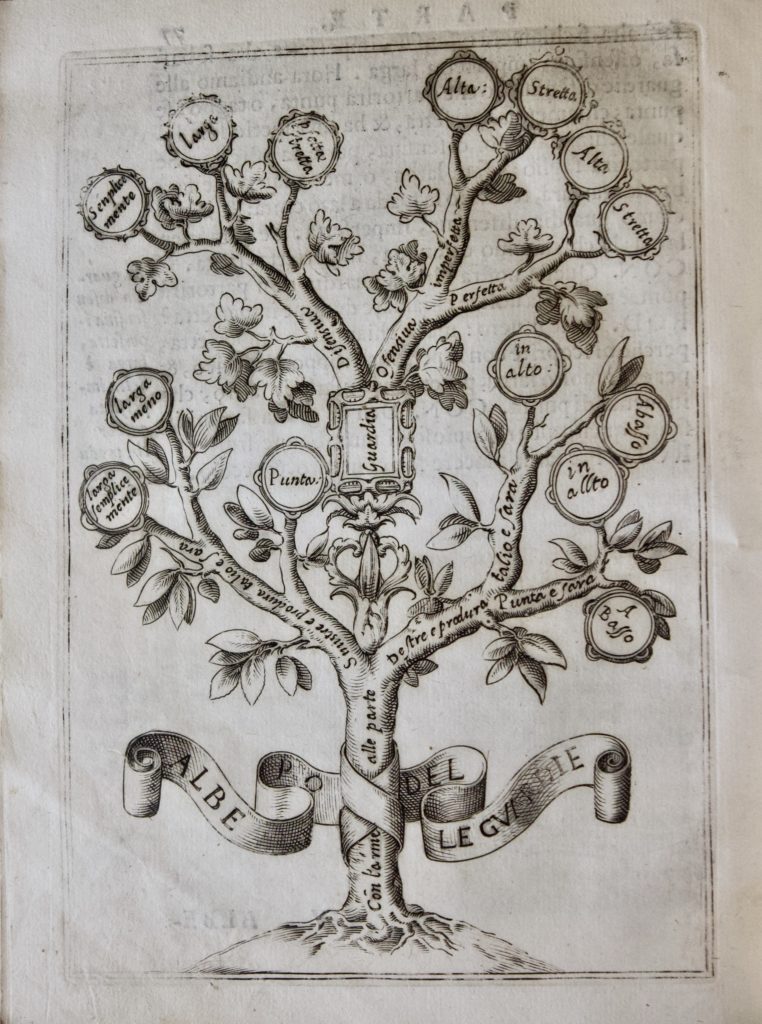

GW: Where it would be as if it was in the sheath. Yeah, so that’s defensiva imperfetta. And then he swooshes it up and then he’s in offensiva perfetta. It’s on the right side, above the head, the point is forward. And then Third Ward is when he turns, the point is back, which is imperfetta and then he cuts down. Oh yeah, the whole book is genius. The tree! The tree of guards.

JW: Which is beautiful, right?

GW: I’ll stick a picture in the show notes so that people can see it.

JW: The thing about it is like reading Manciolino, Manciolino gives this really interesting anecdote. In his introduction, he says that, basically the low guards are good for defending, the high guards are good for attacking and when you’re in a low guard, your natural offence is always going to be a thrust. So I took that and I started really delving into that further and looking at Manciolino’s offences is basically with the sword and small buckler, which is the framework of his system, and then he kind of builds off that into lots of different things. He constantly wants you to work back into it. So for his offences, sure enough, when he’s in coda longa stretta or when he’s in porta di ferro stretta, so he’s in his low guards, either on the right or the left. He either attacks with a thrust or with a falso. And then the secondary intention builds off of that. So a falso would be usually to the hand. We’re talking about sword and buckler here. But he limits it to just that. Whenever he’s in a low guard, those are his basic actions, and the kind of the brilliance of it is Marozzo says this later on, is that when an opponent is in a low guard and you’re fighting them with a sword and targa, you should watch their hand. He says that you should watch their sword hand, and this is another piece that came from that whole lecture is most of the Bolognese masters tell you to watch your opponent’s sword hand. And the reason why Marozzo says with the sword and targa is that if they’re going to deliver a cut, they’re going to have to raise their hand, which is the tempo. It’s the tempo of attack in Giovanni dall’Agocchie. Or they’re going to have to pull their hand back in order to deliver a thrust, Marozzo says. And so taking that and thinking about it, Manciolino is giving you this really interesting idea that if you can constrain your opponent when they’re in a low guard, if you can step into measure when your opponent assumes a low guard as they’re transitioning between different guards, you can basically trap them. So that way, their intentions are very limited, they’re good attacks are limited. And then you look at that from his tactical framework overall, and that’s basically how he plays it out. Now the thing is then when I had made this realisation and really understood this, I went back to Viggiani and I was like, damn it, Viggiani, you are a genius. You have all these things. And really, I didn’t have to go through that entire like thought process. Viggiani had already done it for me. I love what Viggiani has done. And I think that he is probably the most important source. Mostly because he has a great disposition on the guards. He has a great disposition on what tempo is and how to understand tempo.

GW: Yeah. And isn’t it cool how he even tells us how to parry beating the sword away from you, like you’re actually afraid of it? And he bangs on about why it’s dangerous to train with blunt swords because it basically teaches you to be complacent about your opponent’s weapon.

JW: Yes, absolutely.

GW: That’s not how he phrases it, but anybody who has a go at me for doing training with sharp swords like, Viggiani, dude.

JW: So, yeah. And the third thing that I was thinking about is actually like the turns of the body, the postures and the body mechanics. The way that he describes body mechanics is brilliant.

GW: Yes. And that turning that turning of the hips that brings up the back heel. And then when you’ve read Viggiani and you go back and look at Fiore again, it’s like, holy shit, there it is.

JW: Yes, yes, yes, exactly. And that’s the thing. So this whole thing was in the process of when I was looking at Fiore and watching Kurt go through and do the Fiore postures and the mezza volta and things like that, I was like, holy crap, that kind of reminds me of Viggiani a little bit. So I went I grabbed my copy of Viggiani. I was like, Oh. Body mechanics and postures. There’s a lot of really great stuff in there.

GW: Yes, there is. And I credit where it’s due, if I recall correctly, it was Bob Charron when he came to Finland in 2003 to do a seminar for me, or possibly 2005, I think it was earlier, I think was 2003. That he was the one who put me on to Viggiani. He was like, Guy, you’ve got to read Viggiani, I’m like, Viggi-who? And I had a look and holy shit, Bob, you are right. Do you think the Viggiani actually trained in the Bolognese system?

JW: I do. Yeah, absolutely.

GW: And then modified it. His Schermo is one action. It’s a zip file for fencing.

JW: It is, but it’s also basically the exact same advice that Giovanni dall’Agocchie gives for his “how to prepare for a duel in 30 days”.

GW: Right. And it is very, very similar to Fiore’s Plays of the Sword in One Hand, and it’s similar to the “falling under against half shield” in 1.33. And at the end of Capoferro, in his Gran Simulacro, there is a chapter which is the secure way to defend yourself against any blow. And guess what? You wait in a low guard and when somebody attacks over your sword as that’s the only place they can attack as your sword is down and to the left. You beat it up into prima and then you stab them with a lunge. It’s Viggiani. Just pure, unadulterated Viggiani.

JW: In a way it almost represents probably this common approach to sword fighting. And this might be the common fencing of Italian fencing. A lot of times even Marozzo refers to rising and falling. Manciolino refers to rising and falling as actions that you should do. It’s basically false edge to come back with an attack, whether it’s a thrust or a cut. And you see it throughout all of these different Italian systems, you’re constantly coming up underneath your false edge and then coming back down.

GW: And this is incidentally why I think that the Liechtenauer Zettel of the verses and the Meisterhau and what have you are like the advanced course because you see that in the Messer sources, but you don’t see it in the Liechtenauer longsword sources because, well, everybody knows that stuff already. It’s my view. That’s my opinion. And some people do and some people don’t. But to my mind, a system that doesn’t have you starting in the low guard on your left and parrying everything that comes at you with a rising blow is probably missing something.

JW: Yeah, I was just thinking about it. It’s in Palladini too, and he actually sticks it in his cut section. But he tells you that you can do it with the thrust, you can deliver an imbroccata.

GW: If you think about it, if you’re holding a smallsword and you’re en garde in quarte and somebody thrusts over the arm and parry with the false edge and thrust. It’s not necessarily the first technique and it’s not the universal technique, necessarily, but that basic kind of false edge parry from the left and then you strike, it’s everywhere.

JW: So, Guy, Palladini gives one of the coolest counters to that.

GW: Go on, tell me.

JW: Man, when I started studying Palladini, and I got into this parry of this play. I was like, oh, my God, this is the most beautiful thing ever, because it doesn’t seem like it could work. Basically, when somebody comes up with that false edge and they start to turn their sword over to deliver that thrust? He says, to turn your flat over their sword, basically go into guardia di faccia, so you push down their sword with the flat and it’ll basically set their sword completely off and put the point right on their face, right? So that’s the initial setup to the play. It doesn’t feel like it should work. You’re on the other side, they’ve got your false edge coming up and you go with the flat of your sword and just have your sword fully extend in front of your face. And then once you’re in that position of leverage, then you just take a step back with your back foot and let your hand drop, and it just puts the point right in their chest. And it is the most beautiful thing ever.

GW: Have you got it on video?

JW: I will. I’m we’re working on that.

GW: Get it on video for me and send me the video or send me a link and I’ll put it in the show notes and this isn’t going out until February. So you have a bit of time. We’re recording this in October. I’m way ahead on my podcast recording at the moment. You have some time. Do not let the listeners down, sir.

JW: I won’t. It’s beautiful though.

GW: If he fails to get the video to me before this episode goes out, listeners, email me and I will forward your complaints to Josh. I promise you.

JW: Duly noted.

GW: I wouldn’t give out your email address or anything like that. That would be wrong, but I would forward the complaint. Fair?

JW: That’s fair. Absolutely fair.

GW: OK, speaking of listeners, you have a podcast, l’Arte dell Armi, which is the Italian for “the art of arms”. So tell us a bit about your podcasts. I’m fairly sure that some of the people who listen to this show are quite interested in podcasts about sword stuff.

JW: Yeah. So I started the podcast because when the pandemic hit, we kind of lost the sense of community that you get from going to events and getting to sit down with other sword people and have those conversations over drinks or something like that after an event. I was like, I want to get that back, and I want to start engaging in these conversations again because I feel like I’ve always learnt so much from sitting down and just listening to those conversations, like the conversations that happened at Lord Baltimore’s challenge were incredible. I was sitting at a table with Mike Pendergrast and Devon Boorman and just listening to them go back and forth. And I was just like, what world do I live in right now? But to get to get these conversations going where you have this exchange of ideas, I think is so important. It’s one of those things where I think that’s it’s a really great way to learn. And then obviously, the long form version of a podcast allows you to really kind of get those ideas out there for people to really kind of home in and explain those things. And with the Bolognese system in particular. It’s growing. For the longest time, Ilkka was basically like The Godfather.

GW: Let me tell you a story about Ilkka. I think it was 2006 thereabouts, but I was about to get into the Bolognese stuff and Ilkka was studying with me, had been for some years and was working towards his assistant instructor’s exam. And one of the things you have to do for that is to present your own interpretation of a historical fencing system from sources. And he fell in love with the Bolognese a bit before this, and he said he wanted to do Bolognese. And so I stopped doing my Bolognese research because what I was expecting to happen was Ilkka would then do his exam, which he did, and he passed it. Flying colours. And then he would basically do the Bolognese programme for the school. It didn’t quite work out that way. He ended up starting his own thing with some other people. But if Ilkka hadn’t had gotten into Bolognese, I would have done. I only held back from driving into the Bolognese because I was leaving the field open for Ilkka. The problem is, when you are the teacher, it’s very easy for your students to kind of pick up your prejudices and your preconceptions and your biases and what have you. And I wanted him to come at it without any instruction from me. Instruction in research practise and how to write an essay, stuff like that. But not in the Bolognese stuff itself. And so I’m very, very glad that he really did run with it because if he hadn’t done it, I would probably be teaching Bolognese seminars now.

JW: So much of the material that he produced ended up, I think, a catalyst for a lot of people. So kind of going back to the question of why the Bolognese system, one of the great things about Bolognese is in general is that you have kata, you have forms that you can do, and through my fencing career, going out and fighting people, one of the observations people will make when they’ve seen me fence, they’re like, man, your footwork and your control is like, exceptional. And I’m like, yeah, they’re like, “How do you do it?” Well, I do forms for an hour or two hours a day, almost every day.

GW: That will do it.

JW: That’ll do it, I guess.

GW: People are like, “forms are stupid”. “Forms only work if your attacker happens to follow the form exactly”. I had the same conversation with Dr Manouchehr Khorasani on this podcast. I don’t know if you listened to that one, but he’s like, yeah, and those same people who complain about forms are crap do forms. They just call them something else. They call it like a combination. Or very short forms like jab, jab, straight punch or whatever.

JW: I tell people all the time, it’s the coolest way to work out ever. It’s the best workout that you can possibly imagine. You just go out in the field. Sometimes I’ll put some music on and go out there and just go through all these forms.

GW: What music?

JW: I’m a bit of a metalhead. Usually it’s some form of heavy metal, but sometimes I listen to classical music. My instructor, Chris Nolan, our head instructor for the Bolognese system, he loves to listen to The Nutcracker. He says that if you pair The Nutcracker with Marozzo’s forms, it actually has a really awesome flow. So he’ll listen, he’ll do everything in tempo and then he’ll go back and he’ll choose the time when he’s going to break the tempo. And it’s really easy because it’s in a standard timing. There are different ways to go about it, you can make this really dynamic, you can add different elements into what you’re doing. But that’s one of the things that I love about the Bolognese system is that it’s really fun to practise, you can take this practise in a lot of different areas, but so much of that comes from what Ilkka is doing where he taught the forms. And that’s basically what a lot of people in the building as a community knew of the Bolognese system because we didn’t really have the treatises yet. We had Manciolino, from Tom Leone’s translation, and that was basically it. What we knew from Marozzo really kind of came from Ilkka and the work that he had done. Because of the translation that was on Wiktenauer is not the best, but when you finally had this series of publications and the Jherek Swanger doing the Lord’s work and getting all of these treatises translated.

GW: Jherek’s a great guy.

JW: It’s created this explosion of understanding of the Bolognese system. We’re starting to figure things out, right? And so one of the important things about having the podcast is that as we’re in the process of figuring these things out, having these conversations about the things that we don’t understand or that we are trying to figure out, helps to, or at least I hope it helps, to kind of bring these things to the forefront and allow people to listen to what other people are thinking, pull those things in and then start to explore them themselves. Not only that, but there are also aspects of the Bolognese system that I knew that I would never get a chance to explore. So one of the episodes, I talked to Eric Weiss, who’s down in Dallas and Eric is a Bolognese practitioner, but he is also a jouster. He jousted in medieval times and is really cool. So I was like, Eric, we need to do is we need to sit down. We need to take Giovanni dall’Agocchie ’s chapter on jousting and let’s break it down bit by bit. And then let’s Marozzo’s advice for what to do when you’re fighting somebody on horseback and you just have a sword and a cape. And let’s talk about that because you’ve actually had somebody ride you down on a horse and you’ve had to jump out of the way. So let’s talk about what that actually means. What does that feel like? What does it feel like to get that timing right? You know? So those are the things that I really wanted to explore. I think the next episode that I’m going to do, I’m talking to Reece Nelson, who’s does a fantastic podcast on armour. Another gateway thing that a lot of people aren’t going to do is get a suit of armour, though they should.

GW: Yeah, they should. But 20 grand? For a lot of people it’s just not approachable.

JW: It’s not possible. And so in the next episode, we’re going to walk through all of the Anonimo’s pollax and armour plays. I want them to talk about the limitations of armour. We’ve got a group at our school that’s really starting to get into armour and some of their observations about things that you can and can’t do in armour are incredibly fascinating. Your arms don’t quite move the same. You can’t really lift your arm up over your shoulder, depending on what you’re wearing.

GW: Well, if you’ve got good armour, you should be able to put your hands together over your head. Look at Fiore’s sword and armour guards, he has a guard where you’re holding the sword over your head.

JW: But the limitation, I think, is more in the bend of the elbow where you can’t quite get your arm all the way back.

GW: Without armour, I’m keeping my wrist straight, there’s about four inches between the knuckles of my hand on my shoulder. I can press that down or bend my wrist to get it in contact. But keeping the wrist straight it is about four inches. In armour I would say, it’s probably about five inches.

JW: Gotcha. So it’s not that much of a difference.

GW: Yeah, but the armour needs to be tailor made. The treaties are written for people who really are rich and armoured combat is their job. The expectation is you are wearing tailor made armour that works really well. It’s like if you have a treatise on driving a car. Say it’s a treatise on stunt driving. They would expect you if you’re taking this stunt driving course with your car, they would probably expect you to have a certain kind of quality of car.

JW: That makes perfect sense.

GW: Yeah. So I think a lot of the limitations that we get with modern armour is because the armour that people are getting off the shelf or whatever, it may be fairly accurate in terms of, well, there was a lot of people in medieval times who wore armour that didn’t fit properly because they stripped it off a corpse or bought it in a market or got a second half from their mate when they were playing dice. I’ll bet you my watch against your arm armour, because it almost fits me. There was a lot of that going on. But I think for the for the treatises is that we’re looking at the expectation is that the armour was made for you and it was made to a really high standard.

JW: Yeah. No, definitely. But there are some overall limitations of what you can and can’t do. There are also certain ideas that exist in armour, like measure, for example, is going to be closer when you’re in armour. And so you have these inherent things that exist where I feel like you could create either not necessarily bad habits or just kind of misunderstandings of things if you were to go and you were to look at the Anonimo, for example, with his pollax and armour. So to try to understand those things, what are the considerations that you need to make as you’re exploring these different things if you don’t have that experience of doing that thing the way it should be done? So, you know.

GW: OK. All right. So your podcast is basically deep dives on specific topics.

JW: Yeah. So sometimes it’s deep dives on specific topics. Sometimes it’s really just kind of highlighting the practitioners that are out there in the Bolognese community, kind of letting them get their ideas out there. I’ve talked to all sorts of people. A lot of times I’ll just ask them ahead of time, what’s your focus? What are you really interested in? And let’s do a deep dive on it. Let’s just amplify those people’s voices. So that way they get out there. And then people can hear that and say, OK, I like that. I don’t like that. I agree with that. I don’t agree. And so on.

GW: One of my principles for my show, is I hope that about 10 percent of the listenership love every episode. A different 10 percent for each episode, perhaps overlapping 10 percents, if you know what I mean. But I’m not trying to please everyone. I’m not trying to make a kind of general interest show, I expect people to have their favourites and I can think of at least two or three people who are going to be extremely excited about this episode. Not least because at least one person actually emailed me and said, Guy, you’ve got to get Josh Wiest on because he’s Bolognese. Oh, do that! That’s better than just trying to please the general audience, I think.

JW: The cool thing, Guy, and I’ve got to say this because I am an avid listener of your podcast. And it’s funny because when you asked me to come on here and do this podcast, I was like, man, I’ve stolen more ideas from Guy’s podcast because you’ve given me some great ideas, like the barefoot walking and barefoot shoes. I was like, I’m sold, I’m going to give this a shot, and I converted completely to barefoot shoes. Even the shoes that I wear at work now are all barefoot shoes. We had an event and this, I guess, will be in February, back in October, called Octoberfecht. I got a dancing instructor to come out, a historical dancing instructor to teach. And all of these ideas have come from your podcast.

GW: I’m not at all sorry.

JW: No, and you shouldn’t be. It’s fantastic, but I think that that level of learning and just hearing, like I said, hearing different ideas, hearing different voices and co-opting some of those ideas and bringing them into your own practise and study. It just makes you such a more well-rounded and proficient practitioner. So I love it.

GW: I agree. Yeah. So it was Katy Bowman’s episode that converted you to barefoot shoes?

JW: It was, yeah, she got me.

GW: She’s fantastic. Yeah, that was a funny story, actually, because Katy’s like high powered and difficult to get hold of. So you don’t email her directly, you email her assistant who decides whether or not to send you on.

JW: That is power.

GW: And it was extraordinary. I’m a barefoot show person or whatever and Jessica Finley suggested Katy would be great for the podcast and actually my assistant Katie, who actually does all the work for the podcast like transcriptions and uploading everything and the podcast would not exist without her. So she was like, get Katy Bowman on, Katy Bowman’s fab. So I approached her and within like 12 hours – given the time difference, that’s extraordinary – I got this email back, like “Hell yes!” with a picture of Katy herself holding a sword. Because apparently her son who is 10, I think, is mad about swords. That’s awesome. Who got you into the dancing?

JW: I can’t remember the lady’s name. She was talking to somebody who did Elizabethan recreation.

GW: Oh yes. Ruth Goodman.

JW: And yeah, and I think she was talking about cooking as well. But you guys went on this long conversation about dance and how dance was so important. And I was like, oh.

GW: That’s Ruth Goodman. Episode 44.

JW: Yeah, that was great. And so, yeah, I went out and I found one of the best historical dance instructors in the U.S. and we brought her out for an event. And everybody loved it. It was incredible.

GW: Who was it?

JW: Her name is Jeanette Watts.

GW: Jeanette Watts, OK. Maybe I should her for the show, perhaps.

JW: Oh yeah, I’ll send you her information. She’s really fantastic.

GW: Yeah. And the funny thing about these deep dives, like one of the most popular episodes of the last little while was with Cornelius Berthold, which wasn’t even a proper podcast episode. I didn’t actually really interview him. He asked some questions about Capoferro’s tempo, and we ended up having this great long, very geeky discussion about tempo. And yeah, it got maybe 50 percent more listeners in the first two weeks than the average. OK, people are really into the deep dive stuff.

JW: It’s weird because like the for my podcast, it’s started more as just kind of highlighting the individuals and having those conversations. And then the deep dives started happening more and more because I think people were really interested in just kind of like getting… everybody has something they’re passionate about. My passion right now, the thing that I’m really kind of getting into is this whole thing about the guards and really trying to understand what they convey tactically and I could talk about it for hours. And other people, it might be tempo and I’d love to talk about tempo. When I had Devon Boorman on there, we talked about what it was like to train your students and really kind of build them up and create a good structure around how to take your students from an intermediate level to an advanced level. And to get his perspective on that was really great because he’s trained a lot of fencers. And so it’s all over the place. Yeah, it’s good stuff.

GW: Great. OK. So as a listener of the show, you know what’s coming. Tell us, what is the best idea you haven’t acted on?

JW: This is a tough one, because I actually have quite a few good ideas that I’ve never acted on. I’ve never I’ve never been to Europe.

GW: Shocking.

JW: It is shocking. I need to get over there. But I feel like because I have such a curious and inquisitive mind, I have so many things that I will think about and I’ll think I need to really explore that and try to understand that. And then I’ll kind of put it in a box because it doesn’t necessarily fit with what I’m doing at the moment. Studying rapier, I think, is actually one of the things that would be the most brilliant thing that I haven’t acted on because I feel like it would be so much fun and I would love to do it, but I haven’t done it. I even have all the treatises and they’re just sitting on my shelf staring at me and staring deep into my eyes. And I’ve been stuck in this 16th century world and I haven’t quite taken that step into the 17th century. I’ve dabbled a little bit, like Paladino’s as close as you can get. So he’s like my gateway into eventually making that transition, but that’s probably the one that I haven’t done quite so much.

GW: OK, you should definitely study rapier. The thing is, to my mind, because it emphasises a particular kind of play, not to the exclusion of all others, but it really focuses on point control and blade relationship, and it does all of that really specifically. You can take that understanding and apply it to any other system you study.

JW: Yeah, yeah, absolutely.

GW: Without cross-contaminating it, it just gives you an insight into blade relationship that you won’t get anywhere else, I don’t think. Smallsword people are jumping up and down in the back going, “Smallsword, smallsword!” Yeah, but it’s different with smallsword.

JW: It’s actually really interesting because I feel like dall’Agocchie actually references this a little bit in his treatise where he talks about how the fencing of his day is narrow and it’s primarily narrow. And then again, you look at his guards and basically, the guards of dall’Agocchie, he gives you safe cenghiara porta di ferro. He basically condenses the Bolognese guards down to prima, seconda, terza and quarta. Guardia di alicorno, coda lunga stretta, porta di ferro stretta. And that’s his entire system.

GW: He’s getting towards Rapier.

JW: He is. Yeah. And then Palladini, he basically has made that conversion. He uses the Roman system in the names of his guards. Speaking of people talking smack about other fencing instructors, he talks mad smack about Agrippa, which is pretty great.

GW: If I remember rightly, I think Camillo Agrippa, 1553. He was the first person to number guards, wasn’t he? But not strictly a Bolognese person.