Guy Windsor: I’m here today with Ian Davis, who is a historical fencing instructor at Boston Armizare, specialising in Italian fencing from the 14th to the 16th centuries. So without further ado, Ian, welcome to the show.

Ian Davis: Okay, thanks for having me.

Guy Windsor: It’s nice to actually meet. I’ve actually been to Boston, but you didn’t come to my seminar.

Ian Davis: I was aware of that seminar and had intended to go. I don’t remember what happened that weekend.

Guy Windsor: And this is extremely bad manners of me. I was just teasing.

Ian Davis: I don’t remember. I had a very strong desire to go. Because you were teaching coaching, if I remember correctly.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, yeah. I think at least one day was how to teach. One day was how to teach and the other was how to train, or something.

Ian Davis: The people who did attend were under orders to bring value back to the club that we surely knew would be imparted.

Guy Windsor: Well, I hope they did so because it was a fun weekend. And I’m very jealous of you living in the same city as the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Oh, my God.

Ian Davis: You got a chance to go?

Guy Windsor: Oh, yes. I had a free day in Boston. Walking in and you see this courtyard. It’s like she fell in love with Italy in 1450 and just decided to recreate it in Boston. And it’s just miraculous. And I mean, the whole museum is absolutely crammed full of world class art. I mean, she had the first Botticelli ever seen in America.

Ian Davis: Oh, I didn’t realise that.

Guy Windsor: Right. I mean, she was of that level. And also the biggest heist, the biggest art heist in history. About $500 million worth of art was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The story of it is incredible. But you go to the museum and it doesn’t look like anything’s missing.

Ian Davis: So even with the empty frames.

Guy Windsor: There’s just so much stuff. Some of the things I took pictures of included this book just casually sitting on a little book stand. And the book stand was some fabulous 15th century thing. And the book itself was made probably in around 1550, 1600. And they’re just sitting there on the table because that’s where you leave your book.

Ian Davis: She had some of those screens that were like carved wood, Italian screens from the 15th century. And I can get my face right up against it and see that the chisel wasn’t particularly well sharpened in one area. So you can see where it left tool marks and things like that, where you get your face right up to an artefact and you’re like, oh, I can see the work that occurred here.

Guy Windsor: The last time I was in a really good museum with friends was in Washington last year and with David Biggs and Kajetan Sadowski, we went to the Smithsonian and there was some furniture there. The thing is, David’s a good guy. He makes lutes. Kaja is getting into woodworking. And I used to be a professional cabinet maker, right? There was some furniture that had us literally lying on our backs on the floor, looking up at the underneath of a piece of furniture. And the custodian was like, okay. And then they came over and when they realised that, it wasn’t just weirdos being weird, it was actually we had a specialist interest and then they’re like, oh, right, okay. And that’s really interesting. And you can have a look at this. And yeah, they were super nice to us. But yeah, just being able to get your face right up to the piece and really see how it was made. Like there’s a Conoid bench by George Nakashima which I know the piece obviously is world famous if you’re a furniture geek. I’d never actually seen one in the wood before. And it was made about 50, 60 years ago. And it is still dead flat. And it is a like a two and a half inch thick piece of, I think, walnut, if I remember right, and it is still dead flat. Like how did he manage that? I mean, he must have come at the thickness bit by bit. Plane off half an inch maybe, or a quarter of an inch each side, something like that. Leave it to settle. Plane off a bit more, leave it to settle. Plane off a bit more, leave it to settle. I mean, just sneak up on it so that all of the internal tensions and stuff have worked themselves out by the time you get to the final thing. Oh, my God, just stunning. But the average listener does not tune in to hear me wank on about furniture. So shall I get on with actually interviewing you? All right. So are you still in Boston?

Ian Davis: I am. That’s why I’m all bundled up this morning. It’s not even cold, but it’s wet because we’re near the ocean. So, yeah, I’m in Boston. I’m a transplant. I grew up in Indiana and then came to Boston after my stint in the Peace Corps because a bunch of my Peace Corps friends were here. So it became the city.

Guy Windsor: Okay. I didn’t know you were in the Peace Corps. Some people won’t even know what it is, so why don’t you tell us what it is and what you did.

Ian Davis: The Peace Corps is not going to like me saying this, but it is largely a cheap, benign propaganda program where the U.S. sends Americans all over the world, largely so that people can get to know an American. It really is. You know, we get embassy passports. We’re not under like contract or passports or anything like that. And my job ostensibly was a youth development volunteer. So I lived in a small rural village in the Andes, at high altitude in Peru.

Guy Windsor: Really? Where in Peru? I used to live in Peru.

Ian Davis: You did? Okay. I was in Chiquián which is right near the, do you know the Whitewash mountain range? Near Ancash.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Yes. That’s a bit of Peru I never went to.

Ian Davis: Okay. Yeah. Not a lot of people get deep in Ancash.

Guy Windsor: That is really remote.

Ian Davis: Yeah, there was a bundle of maybe six towns in this valley, but we were 200 kilometres from Huaraz. And we were 6 hours from Lima, just straight out into the mountains. So I say ostensibly because it was a farming community where when the kids got off school, they went and worked. And in the summer, Lima was one bus ride away. So most of the kids went to Lima to hang out with family. So I hung out, I whittled, I tried my best to do projects. The idea is that you’re doing development work. I help develop a new youth leadership curriculum that was focussed on the youth in the area, generating and defining what that looked like. And I proposed it to the Muni. Didn’t hear back for most of two years. And then actually in my final week before leaving, before my service ended

Guy Windsor: Is the Muni the municipality of the town?

Ian Davis: Yeah, the municipality. They finally showed up like, yeah, we’d love for you to run this program. And I was like, Oh.

Guy Windsor: Honestly, that sounds, from my limited experience, that sounds a very Peruvian approach.

Ian Davis: The good news is Peace Corps is very iterative. They always drop somebody, you know, there’s always somebody next. And so I wrote a nice report and said, basically, people around here want a tourism business volunteer. And the national office listened. The next person who came in was a guy with a background in tourism and a business volunteer. And he couldn’t even find time to leave site. Like, he couldn’t go into our Huaraz because he was just constantly working. So, you know, that’s how it goes.

Guy Windsor: So the net result of this is a bunch of people in the Andes think Americans are nice.

Ian Davis: Right, exactly. And, you know, the first question I got asked when I arrived was like, oh, so you’re American. What’s with all the war? Was actually the first question my host posed to me. And I was like, man, I don’t like it either. Let’s talk a little bit about how you know.

Guy Windsor: So did you speak Spanish before you left?

Ian Davis: Not well.

Guy Windsor: You spoke it pretty well by the time you go home.

Ian Davis: Yeah. Nobody in my town spoke Spanish. I learned the tiniest bit of Quechua, but nobody really spoke Quechua in my town.

Guy Windsor: So hang on, what language were they speaking in your village?

Ian Davis: Spanish.

Guy Windsor: So your hometown in America no one spoke Spanish.

Ian Davis: I go there and nobody speaks English, so I had to learn Spanish. And it turns out I learned, and this will loop us back to swords. It’s relevant because the type of Spanish that I learned a generation or two ago, people were kind of forced to transition from Quechua to Spanish. And in that transition, people learned like very formal, old timey Don Quixote-esque Spanish.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Ian Davis: And so then that evolved into what I learned. And the end result was I can pretty well read Italian. Like 14 to 16th century Italian. I can actually pretty well read it.

Guy Windsor: Honestly, my sort of segue into learning Italian martial arts was I found that because I spoke Spanish from living in Peru as a teenager, I could pretty much handle the Italian at a basic level, just from the Spanish I knew. It didn’t take that much to convert. Although now, of course, they’re mixed in my head. When I go to Spain, I try to speak Spanish and some Italian comes out and when I go to Italy I try to speak Italian and some Spanish comes out and it takes me a day or two in country to actually kind of sort out the mixture in my head into one language or the other.

Ian Davis: That’s fascinating. So you grew up in Peru?

Guy Windsor: Yeah, I lived there from 1986 to 1992.

Ian Davis: Okay. Yeah.

Guy Windsor: My dad was working there. He was a vet and so he was setting up a veterinary field service in southern Peru. So we lived in Arequipa for six years.

Ian Davis: Arequipa is beautiful.

Guy Windsor: Arequipa is lovely. It is, of course, the finest city in Peru. And anyone who says differently just doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

Ian Davis: They haven’t been to Arequipa if they don’t agree.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, clearly not. Yes. So the Spanish did turn out to be super useful, though I mean, my Spanish was the chatting to my teenage friends Spanish rather than formal classical Spanish, which means that I seriously struggle to read a 16th century Spanish source because it has so much specificity and so much formality in the use of language. So I’m not familiar with I’m constantly like digging out dictionaries and struggling along.

Ian Davis: It’s awful.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Ian Davis: There’s a reason I didn’t wind up with destreza.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. I find the destreza sources to be somewhat, on the one hand they’re often very academic, but not actually sufficiently technically specific.

Ian Davis: Yeah. 500 pages for something that, you know, destreza in its core could be summarised on a on a front and back of an eight and a half by 11. But instead we have 500 pages.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So I prefer like Fiore, he tells you, “Await the peasant’s blow in a narrow stance with your left foot forward.” Now that’s the kind of instructions I need. So how did you get into actually practising historical martial arts? So you move to Boston because you have friends from the peace corps there, and then something happened and you got into swords.

Ian Davis: Yeah. I was actually reading about and researching HEMA long before I came to Boston. My original background was Filipino martial arts and it would have been 2013. Someone pointed out that there was this issue where Spanish martial arts had like heavily infected traditional Filipino martial arts. And I was I was fascinated by that question, like, okay, well, to what degree? How so? The Spanish had martial arts. What are you talking about? Which makes sense, right? Like Escrima, you know?

Guy Windsor: Yeah. It means fencing in Spanish. And they have spada and daga.

Ian Davis: Of course. And I was like, oh, that’s interesting. So I started researching. I started on the question of what is kind of true original Filipino martial arts. And then that led me into, I’m starting to look at I see these books where there’s diagrams and stuff showing sword interactions and things, and I was like, wait, there’s like a scientific theory here? That’s very odd and different from how I’ve approached the problem. And then that just opened up into historical fencing in general. The first thing I was looking at was actually Bolognese because I was looking at the destreza and I was like, I can’t I can’t wrap my head around this. There’s not enough pictures. So next step, Marozzo.

Guy Windsor: Who is no better a writer, it must be said.

Ian Davis: Well, I mean, I’m sure he’s very cogent if you’re his dear son Sebastiano. But for the rest of us.

Guy Windsor: But I think Sebastiano didn’t really actually have to read the book, he could get daddy just to tell him what to do.

Ian Davis: So yeah, I started looking at that. My background in that is I figured out they had two swords and I was like, oh, that’s got to be like double stick. And not really at all. Very different approach to that problem. So I had a bunch of, you know, I started with Egerton Castle and Alfred Hutton and it slowly dawned on me how wrong they were about most things.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, okay, okay, okay.

Ian Davis: Maybe not wrong, but pushing it through a particular lens.

Guy Windsor: Okay, when it comes to classical fencing and the sort of sabre fencing of the late 19th century, they are spot on. But when they’re looking at the, shall we say, 17th century Italian stuff through the lens of, well, actually, swordsmanship has improved and developed and evolved over the last 200 years. Obviously, it’s better now. And they were wrong in that. So their lens was wrong. But yeah, I have a huge affection for them because I got into this art with martial arts because I found Hutton’s The Sword in the Centuries in my granny’s house as my grandfather had been a fencer. And it’s like, oh, my God, there’s, like, actual martial arts from sword period. Yeah. Oh, my God. I have to find out more.

Ian Davis: No, I love them. There wouldn’t be modern HEMA without the 19th century HEMA movement, because there were some records we could read. I just always chuckle at like trying to look at Bolognese fencing in the terms of like, you know, parry and quarte, parry and sixte, it’s like, guys there was a lexicon here. You could have learned it.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And again, one unfortunate artefact that I personally picked up was for the first few years of my own historical martial arts training in early nineties. I was basically trying to get the historical martial arts I was looking at to fit my sport fencing background. So any parry on the inside was the equivalent of a parrying in quarte when in fact the whole notion of how a parry should be done with a medieval sword is fundamentally at odds with how you do it with a foil. You don’t interpose your forte with their debole, or your forte to their foible. Whenever you want to call it. You hit the sword away middle to middle. That’s still true in the Bolognese. But if you’re thinking parry, quarte, when you do an inside parry, you’re just going to be doing it wrong. Which I was for a long time. You know, you learn, eventually. You get enough broken fingers and you pick up some things. So you got into Marozzo? Then what happened?

Ian Davis: Yeah. Kali, destreza, Marozzo. So then I went to the Peace Corps, and I had a lot of time to read, and so I did a lot of reading. When I was in Huaraz I could jump online and download as many HEMA PDFs as I could get my hands on.

Guy Windsor: Okay, so what year were you there?

Ian Davis: I was there 2014 to 2016.

Guy Windsor: Oh, quite recently. Okay.

Ian Davis: So, yeah, I was just reading a lot. Came back with some slightly better notions, like I’d kind of disabused myself of some of the ways that I was viewing it from the Kali background. But I wasn’t like a practitioner yet. And when I was looking at where to move, I came back to Lafayette, Indiana during the election cycle and won’t get political. But basically I said to myself, it’s time for me to go. So I moved to Boston, at least in part because Boston Armizare was here. I’d been looking at a couple of cities and this was one with a well-organised HEMA club. So I moved here and just showed up. I didn’t even do the beginners class. I walked in and was like, let me show you things that I know. And they were like, Yeah, that’s fine. You don’t need to do the beginner class. And then I’ve just been at it with them ever since.

Guy Windsor: Okay, so what is your main area of interest?

Ian Davis: These days it’s almost exclusively wrestling, dagger and harness.

Guy Windsor: Oh, really? Yeah. So you’ve abandoned the sword altogether. But this show is called The Sword Guy, so I think you have to stick with swords if you’re going to come on the show. That’s the rules.

Ian Davis: I love the long sword as a bayonet. I’m really into that. And there’s the guard of breve and we see Bicorno in harness. We see mezana porta di ferro. So it’s there. But I’m really interested in that like body contact, distance and spear and poleax and all that. I built out a harness over the past couple of years and have done some fighting in that.

Guy Windsor: Okay, so are you starting out with an interpretation of Fiore or are you starting from some other place?

Ian Davis: Yeah, when I started transitioning into harness, my big focus was actually on the material culture. My background is anthropology. It was a four fields approach.

Guy Windsor: And what is the four fields approach?

Ian Davis: Uh, bio anthro, linguistics, cultural and archaeology. I believe it’s been a couple of years.

Guy Windsor: So basically, your anthropological standpoint includes language, material culture, biology stuff, archaeology stuff. That sort of thing.

Ian Davis: And so I took that approach and I said, okay, well, step one is material culture. I want to get to know what it feels like to wear armour. And so building the harness was a big piece of that and then started actually from physical testing against historical mail replicas. I wanted to find out what it actually took to stick a sword point through historical mail on a freestanding target.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Tell us a bit about that, because that’s always interesting.

Ian Davis: Well, yeah. So what I used was basically we have essentially a pell and put a heavy bag on that. On the face of the heavy bag was padded armour and then some eight millimetre I.D. mail. Good, like one millimetres thick wire, a good reproduction, all individually riveted. Actually some nice people in, I want to say Finland, handmade this mail.

Guy Windsor: For your tests.

Ian Davis: Yeah, they were trimmings off of my first mail shirt. There are some aspects of you’ll still see things where, like, people will come and place the point against the mail and then kind of couch and drive and on a freestanding target that tends to just shove it backward.

Guy Windsor: You’re not going to split the links with that.

Ian Davis: No. Right. But once you move out to I’m going to settle it in, this is arbitrary and there needs to be better testing, I will say, but about an arm’s length distance for at least my body from the target so I can move my body into it and generate that impulse. You can get link compromise or link breakage. And so starting from that perspective, right, if I’m going to actually punch through mail, I need to deliver a thrust from at least an arm’s length away. Proved to be very effective. And then there are other aspects of this. You know that image of Posta Breve from the PD where it’s like all the way up under the arm, the right hand is all the way up under the armpit. The cross guard’s braced across the breastplate. You’ve got the book right there.

Guy Windsor: So I of course I have the book right here. I’m in my study. Right. Okay. I’m just going to make sure I’ve got the right one. And then, of course, we will put it in the show notes that people can see what we’re talking about. Posta Breve la Serpentina. The first guard here?

Ian Davis: Yeah, I believe so. So that like couch structure versus if you look in the Getty, the rear hand is a little lower. In my mind, I put the two of those as a continuum. We’ve got a stop motion.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So you go from here to fuck you.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And brace it up. If you want to pop right through mail, putting it like that. So adopting that couched position and then just to a crescent pass right against the left foot, pass the right foot. I’ve put two thirds of a blade through a heavy bag through mail that way. Maybe about half of the blade, probably.

Guy Windsor: So as you’re getting about a foot and a half of steel into the body. Through the mail.

Ian Davis: Through the mail.

Guy Windsor: That’s what we like to hear.

Ian Davis: It works, right? It’s replicable. Anybody else can go set up a freestanding target.

Guy Windsor: Okay, because this actually is super important, because it totally changes how armoured combat can or should be done. So what you’re saying is basically, if you stand there and you use your arms to shove the swords through the mail, it’s unlikely to work. But if you couch the sword against the body and walk it through, it punches through much more effectively. So tip speed is less important than the mass you put behind it for this.

Ian Davis: I think what I would say at this point is it’s a little column A, little column B. And so from doing this, I think you need a ballistic hit to compromise a link. And then in the next, you know, millisecond mass needs to go through the target.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So basically, the point needs to be moving quickly and you hit the link hard then the weight comes through.

Ian Davis: Yes. And if you separate those two, it actually still works as long as you get your first compromise right. My buddy Adrian, who his background was actually infantry and so he’d done bayonet training and stuff. And he came up and just hit it bayonet style and it didn’t go. But he left it there, right? He left it extended. And I was like, okay, now turn to the couch position and drive up into it. And we heard this disgusting pop, and then it just suddenly jumped forward, couple inches into the target. So the key piece is compromising the link, which takes a ballistic hit.

Guy Windsor: Do you have all this written up anywhere?

Ian Davis: Not written up. I’ve got video on my YouTube channel and on my Instagram.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Drop me a link to put into the show notes and we’ll make sure the video is there in the show notes so people will be able to see this. I have a feeling that this really ought to be an article.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And I don’t think necessarily it was scientific enough yet. I’d like to get a sled or something that is generating consistent force. I’d like to get a standing target that’s my weight in my harness and try it like that. But it’s certainly something that could be written up because I think there are rule sets where I see people like kayak in and kind of place their point and it counts and that just shouldn’t count.

Guy Windsor: Well, it depends, because one of the things you can do from that position is go into a takedown.

Ian Davis: Yeah. Okay.

Guy Windsor: And once you’ve got the person on the ground, when you’re in armour, your sense of gravity is about maybe anything between six and 12 inches high than it is out of armour, generally speaking, which means it’s quite easy to tip people over. And when they’re on the ground, then you can slam the point in wherever you want. And you can go through the visor or whatever.

Ian Davis: Couching and driving against a downed opponent. We’ve done that. Put the bag on the ground. That works, too, right? Especially if you place the point and you kind of give a little hop, 240lb hitting like a hammer on the cross guard. And actually with a dagger, you don’t really even need that distance, especially if it’s a specialist dagger. And so you can stand fixed footed within that arm’s distance and put a dagger through as long as your elbow is near your core.

Guy Windsor: You’re connected.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And that’s where if you go look at what Fiore has, you mentioned takedowns and things. It’s extremely binary. We have the guards and their thrusts. We have the vera croce or croce bastarda, which as you enter trying to hit me, you’re coming from beyond that arm’s length distance. And so it’s just the exchange of thrusts, you walk on to my point your energy. And as long as I’m fixed and solid, I can receive that and punch through your mail. So there’s that, there’s thrust and crossings from distance and then all of the plays are wrestling, including, lift the guy’s visor up and stick him. You’re probably not going to like couch and drive through mail in that wrestling distance, but you can do other things to get around the armour. And that’s what we see in the book. I found that really interesting, starting from the material context and then coming to some conclusions. And then I go and look at the book and I’m like, oh.

Guy Windsor: I’m curious as to why you can do it with a dagger when you can’t do it with the sword at the same measure.

Ian Davis: I think attachment and stiffness, the dagger is just much closer if you have your elbow attached and actually especially with a non-specialist dagger. If I throw a strike where my arm extends and my elbow is distant from my body. Mail will stop it, no problem. I’ve got one of the Todd Cutler Wallace collection rondels. You can do whatever you want. It’s going to go through with that particular piece.

Guy Windsor: Well, that’s the thing because we see specialist daggers designed for armoured combat, which have that sort of mail splitting quality to them. And we also see swords with similar point geometries. So what kind of sword are you using for these tests?

Ian Davis: Type 15. I’ve got a type 15 arming sword, not the A with the extended grip. And that’s mostly what we’ve used. We’ve used those, those crappy Hanway, I actually love them but they’re cheaper Hanway bastard swords, those worked okay.

Guy Windsor: You sharpened them up though, surely?

Ian Davis: Yes. Yeah.

Guy Windsor: Because they come blunt, right?

Ian Davis: Sometimes. Cult of Athena in the U.S., you can have a sharpening service so you can buy it sharpened from them. But then we also tried out. Do you remember Mike O’Brien? He did attend your workshop. He’s one of our coaches.

Guy Windsor: In case he’s listening, I’ll say of course I do. Absolutely. It was three years ago now!

Ian Davis: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And pre-pandemic.

Guy Windsor: Of course, that’s right. Four years ago. It was April 2019. Jesus, I need to get back to Boston.

Ian Davis: Before time ended.

Guy Windsor: Yes.

Ian Davis: But he has an Albion ringeck. And that was really interesting because in terms of the degree of diminishment from a couch and drive. I’ll actually caveat my own statement about arm’s length if with that Albion ringeck the point is so fine that you get nearly three inches into the target without compromising a link at all. Which in the right spot.

Guy Windsor: A lot of the historical mail is a lot finer than the stuff you’re using. If you said you have eight mill rings. Some of them are like three.

Ian Davis: Yeah. Right. You’re not getting a mail standard. You’re not getting through that, probably. That’s why it’s like, why would you if you could just wrestle the guy down and flip it up and then stab him in the back of the head, which is in Fiore. The different weapons definitely matter. Doing dagger tests with like the Todd Cutler Baselard where the tip profile is much wider. That’s very hard to get through except for, interestingly enough, the reverso by which many men have lost their lives. That with good elbow attachment you can have the crappiest. I’ve done it with a bollock dagger. So a completely non specialist work knife, the reverso with good elbow attachment can punch through mail.

Guy Windsor: So you’re saying that for mail penetrating purposes, a reverso is more effective than a dritto?

Ian Davis: I think so, yes.

Guy Windsor: That doesn’t surprise me at all. But it is counterintuitive to people who haven’t done a lot of cutting.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And it’s the setup that you need to do that. So Fiore, we fire dritto. They put the hand in the way, we counter grapple. The reverso goes into the chest, elbow press the reverso goes into the back, it takes, if I just cross chamber my dagger and present my elbow to you, you’re going to put a hand on it. And now I can’t do it. So built into the anti armour work is concepts like first intention, second intention. All of that is necessary set up.

Guy Windsor: And here’s the thing, when it comes to power generation, there’s this myth that the step helps you generate power. But if you’ve ever seen a lumberjack cutting down a tree with an axe, they do not ever step. Because you get vastly more power if both feet are on the ground. And so you can drive off the feet and with a hip rotation, slam whatever it is you’re slamming into, whatever it is you’re trying to hit. So I think a lot of what’s going on is that first mandritto is getting you safely across distance into measure, and then your feet are planted. So the extra force you’re getting from that reverso is coming from the fact that both feet are planted and you’re driving it off the back leg.

Ian Davis: Core rotation, all that. I think what’s interesting about that too, when we’ve added a thrust against mail only counts for us when it’s delivered from at least an arm’s length away or received from an arm’s length away. That makes it easy for judging, right? I look with my eyes. And if the two people started from a good enough distance and the thrust lands, great. I don’t have to worry about much in the way of quality beyond that. But what it results in is this very like two people kind of circling each other and positioning and all those guard transitions and stuff that Fiore is harping on about. That’s where you trap people, right? Like I go to that high serpentina guard, feint it, I get somebody to raise their hand and that’s when I step in and drop my hands and hit from low. Things like that where there’s a lot, it results in a very different looking kind of armoured fighting. There’s a lot of entrapment, I think, that it creates.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, and there’s all sorts of implications for that in the text. For example, in the poleax section where dente di cinghiaro is opposed by posta di donna destra. He says that by stepping the front foot out of the way as you strike, the parry will fail because you’re angulating the attack. So the parry from the dente di cinghiaro would clear it. No problem. But because you’re coming in from around to the defender’s. right, you just angulate behind that parry and strike. And of course, if they know it’s coming, it’s the easiest thing in the world to parry. But if they think it’s coming straight at them, their parry just fails and they get smacked in the face.

Ian Davis: Yes.

Guy Windsor: It is incredibly satisfying.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And you had Liz on here, really interesting talking to her about mounted combat and the ways that two people are running at each other. And because the timing needs to be so perfect, if you just pull back on your horse for a split second and get the stutter step out of your opponent, then you hit and they don’t. It’s stuff like that that I think there’s a really deep layer that quality rules like this start to allow to be expressed, like we know they’re there because of things like you just pointed out, right? We know they’re there. But if I for example, with the poleax, we require that that lands unimpeded. If you get your haft kind of in the way, even if it’s crappy, we’re going to ignore it, right?

Guy Windsor: Yes, because the armour will take the rest.

Ian Davis: Right. But to land an unimpeded poleax strike.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Okay. I’ve received an unimpeded poleax strike on my armour before and yeah, it’s rough.

Ian Davis: There’s like a specific line in the ruleset that I’ve been using that’s like force does not matter for this. Land it unimpeded. I don’t want to watch people get concussed through their armour. I fought Connor Kemp Cowell out of Philadelphia this past December and there’s one where I was able to like feint with the heel, draw him out to one side and it sounds like a car accident when it lands. And it’s stuff like that. He was fine.

Guy Windsor: What poleax heads are you using? Are you using the rubber ones?

Ian Davis: I like the hellgies, specifically.

Guy Windsor: Rubber?

Ian Davis: Yeah, they’re rubber. They’re a rubber head. In order to be able to hit people sufficiently, in my opinion, I think I like the rubber poleax heads and I just recently made aluminium blade, you know, the Rawlings synthetic swords.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Ian Davis: I just made an aluminium blade, two aluminium blades for that, that all the same fittings come on so I can smack people with the cross guard and not actually hurt them.

Guy Windsor: So you’ve got an aluminium cross guard.

Ian Davis: No.

Guy Windsor: So why are you using aluminium blade? Why not use a steel one?

Ian Davis: Lightness, ease of production. One of the things that makes poleaxes safe enough to hit each other with is just getting rid of some mass.

Guy Windsor: Oh, I see. Right. So you’re using the aluminium blades to reduce the overall mass of your sword as held like a poleax.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And for cheapness. Harness is already a really expensive thing to get into.

Guy Windsor: When I need to equip a whole bunch of people with poleaxes for a seminar, right? It’s simple. What you do is you take your regular quarterstaff type sticks. Two metre sticks and you take a longsword and you duct tape the longsword to the stick.

Ian Davis: That’s a great idea.

Guy Windsor: It is so easy.

Ian Davis: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: Okay. You then have the cross guard which your axey bit. So you do have to be careful not to actually smack it through people’s masks or whatever. But it handles a lot closer to a poleax than you might think because the mass is where it should be. It’s about the right size, sometimes a bit long. If your stick is a bit short, you can let the sword poke out a little bit. But also the fact that the connection between the sword and the stick is just duct tape, it’s got a little bit of give in it. And it’s not going to take repeated abuse. So you can make it a bit safer by using less duct tape.

Ian Davis: Right. I like that a lot. So I want to be able to throw cross guards strikes and pommel strikes in the wrestling distance because it’s in the text and from using that type 15 arming sword, if you basically throw a right hook with landing with the cross guard on fixed foot. Right through.

Guy Windsor: Right through mail, are you saying?

Ian Davis: Right through mail. So there’s no safe way to do that strike with a steel cross guard or arguably with a metal one. So that’s where I wanted to take a standard fitting set that people have access to. Most people own one of those rawling synthetic swords, right?

Guy Windsor: I don’t. I don’t have any plastic swords because I hate them.

Ian Davis: Okay, well. And I have not used my Rawlings for years anyways, and this was a way to like, bring them back into use. But, you know, you screw everything off, pull the grip, the cross guard, the pommel, slide it onto an aluminium blade. Now you have a specialist armour sword and you can hit people with the cross guard because the crossguard will just kink. It’s plastic and it’s got a big ball.

Guy Windsor: The crossguard is plastic?

Ian Davis: Yes. And the handle is synthetic. So I can whack somebody in the head with it and it might ring their bell a little bit.

Guy Windsor: Oh, I see. I’ve got the wrong image in my head because I don’t use plastic swords at all. I seem to remember seeing these nylon bladed swords with a steel cross guard and a steel pommel. And I was like.

Ian Davis: Those are the penties.

Guy Windsor: I wasn’t seeing the safety advantages. It is a plastic crossguard and a plastic pommel. Now I get it.

Ian Davis: And you can bonk people really hard and we’re not going to John Clements anybody your partner is wanting to throw up in their helmet. I don’t know if you’ve seen that video. But yeah, a guy who eats a pommel to the head and it works.

Guy Windsor: Of course it works. It works extremely well. But yes, there are good reasons why we don’t to do that to people.

Ian Davis: Unless we have the right equipment, then we can, with some control.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, yeah. I mean, my feeling around the whole safety thing is it’s your behaviour that makes things safe. You can make anything dangerous if you choose to make it dangerous. There are some people who get their knickers in a twist when I mention doing light sparring with sharp swords and no safety equipment. It’s not some holy grail of ultimate sword fighting. It’s just another training modality which will teach you certain things you won’t learn anywhere else, which you can then later apply elsewhere. And it’s just really interesting and useful. But the risk profile doesn’t suit everyone, and I’m not suggesting ever that everyone should do it. I’m just saying that it is something that I find extremely useful. People say, oh no, safety, safety! But you drive a car.

Ian Davis: Right? Well, Pekiti-Tirsia Kali, part of my background. We did lots of light blade work, both knives in the close range. Knives in the close range, you probably need to be doing pattern drills that you all know, it’s way too close. But once you back out into the largo distance, which still called largo in Kali, also.

Guy Windsor: Interesting.

Ian Davis: You can use a live blade and just not hit the person in the arm. And you can do bridging and grappling and all of this stuff is integrated, but it takes a lot of precision and it takes not going super hard.

Guy Windsor: And then you take some of that precision and apply it when you’re using a safer training method.

Ian Davis: Yeah. You’re learning a skill set that it’s a different skill set because you’re trying not to hit a person. But if I could stop a sword three inches off your arm, I can stop at three inches through it.

Guy Windsor: True. I was on one of these courses run by a friend of mine who does mostly Filipino type martial arts, and it was a series of knife courses. We were doing this pattern drill, sharp on sharp, and the attacker comes in and you do something and you end up with your blade right against their throat. But of course, you stop it three inches short because it’s a sharp blade. So I’m doing this and I know the guy reasonably well. It’s somebody I’ve been to seminars with before we’re going a bit quick. It’s my turn to do the thing. And I’m using a single edged knife. So the back is blunt. So I go in just flip it to the back and stuck it in. Don’t do that at home, it is naughty and bad. It was so much fun.

Ian Davis: You’re in England these days, right? I hope more HEMA people go actually talk to this guy. Are you aware of Nadar Singh in Shastar Vidiya swordsmanship?

Guy Windsor: Yeah I’ve heard of him. I’ve seen some newspaper articles and stuff on him, maybe I should ask him to come on the show.

Ian Davis: And I would like to just get more people. So they do a lot of sharp on sharp training and apparently sometimes put the armour on so they can actually touch each other too. That’s a place I want to go to is like if I have harness, let’s blunt the tip off a sword. You can cut me. I’ll be fine. Because armour works, right? So we could do unarmoured longsword with clip tips in harness. And it’ll work. We’ll be fine. The sum of the modalities of live blade training they’re using in Shastar Vidiya. And you see, there’s one clip from some martial arts festival. What you said reminded me of this, where they’re on a slightly springy floor. It’s like a gymnastics floor and not a solid ground. And one of the students, he’s showing some like dealing with multiple skirmishing kind of stuff. And he’s facing one direction. He turns around and puts the point out towards this guy’s throat. And the guy is on this springier than expected floor and is coming forward again in the air and you see that his body is up. He has no way of stopping his motion and midair just turns the flat and slaps him in the chest with it as he walks past. I have to be like, buddy. And he pulls the microphone up and explains what just happened. So, if a guy can do that, sometimes you’ll see people that are like, oh, it kind of looks like everybody’s being compliant. I haven’t gotten to feel the energy, so I would love to get people there. I trust your opinion, right, if you can work with them. And you say, oh, well, this is kind of my view on it. I take that as, you know, something approaching gospel.

Guy Windsor: That’s very flattering. I’ll look into it again. I’ve been meaning to get in touch with the wider martial arts community here in Britain for a while, anyway. COVID didn’t help. And I’ve been sort of head down with other stuff since. But yes, I’ve actually been thinking about reaching out to our Sikh friends.

Ian Davis: Why are there elephants and Fiore and tigers?

Guy Windsor: Why wouldn’t there be?

Ian Davis: Yeah, the thing that I’m interested in and one of the reasons why I want to get people with the Italian background in contact with the Shastar Vidiya folks, in Pagano, there’s this brief reference where he says regarding the history of Italian martial arts, he makes some passing comment about how the Romans encountered pieces of it in India and brought it back.

Guy Windsor: That’s a very difficult argument to make.

Ian Davis: It is, but I think it’s there.

Guy Windsor: Remember Hannibal and his elephants. If you are going to get elephants and lions and stuff. Well, first of all, there were lions in Europe until relatively recently. They’re sort of hunted to extinction in Europe. I forget when, but it’s relatively recent. Elephants, I mean, the Romans were in Africa, right? If you’re going to get an elephant to Italy, which is easier, getting it from India or getting it from Africa. Which is closer?

Ian Davis: I think it’s just more of a curiosity. It’s not like an actual academic argument that I want to make, but there’s pieces like The Sword in one Hand, right? We start in guardia, sotto il braccio.

Guy Windsor: That’s not what Fiore calls it, but never mind.

Ian Davis: Sure, it’s something we see over and over again, through a couple of texts.

Guy Windsor: Point pulled back and sort of low on your left side, held in the right hand.

Ian Davis: And that’s how most of like Shastar Vidiya forms actually begin with like a low cut coming out of that. So it’s just kind of interesting. It’s a curiosity.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, it would be very interesting to see. It is worth remembering that India had a massively sophisticated material and other culture, centuries before we did in Europe. Look at what the Indians were doing in 800A.D. it is like, really? How come they didn’t just come over and colonise us?

Ian Davis: Indoor heated baths in Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

Guy Windsor: Well, to be fair, the Romans had those. Honestly, central heating was better in Britain in Roman times than it is now, I think. Honestly, the British do not know how to build houses and they don’t know how to heat them or insulate them either. I mean, I lived in Finland for a long time and my standards are somewhat higher than what we find on this benighted island. I’m getting slightly off topic. I have a note here to tell me to ask you about bringing Fiore into the modern combative self-defence context. Okay. This is very contentious ground. So I’m curious to hear what you have to say about it.

Ian Davis: Sure. So I’m going to start with a shout out to the greatest living Fioreist named Craig Douglas.

Guy Windsor: Never heard of him.

Ian Davis: That’s not surprising. And Craig Douglas, as far as I know, has never picked up a longsword in his life.

Guy Windsor: So how is he a Fioreist then?

Ian Davis: So his background was he started in the military, left the military, became a police officer, went from regular officer to a SWAT guy, went from SWAT guy to doing undercover work for the DEA that had him buying drugs, doing basically entrapment and all sorts of just wild stuff. And essentially he almost died several times in that line of work, as one might expect. And he realised that his training was not adequate or suited to the realities of his work. And so he got some people together and he said, okay, we’re going to take these simunitions guns and we’re going to violate the manufacturer recommended safety protocols and use these at contact distance.

Guy Windsor: Oh, Jesus, that would hurt.

Ian Davis: Yeah, this finger, is there a scar there? There’s a shadow.

Guy Windsor: Well, the whole thing that seems a bit wobbly.

Ian Davis: I took a sim round there during one of his courses.

Guy Windsor: Okay.

Ian Davis: But the long and the short of it is, through lots and lots of competitive, combative fighting with sim guns in the contact range he reinvented Remedy Master, Abrazare. He found out that the optimal combination for what he calls vertical grappling in a weapons-based environment is…

Guy Windsor: Hang on. Stop. That key phrase, “vertical grappling in a weapons environment”.

Ian Davis: Is that not the definition of HEMA?

Guy Windsor: It’s the definition of basically the first third of Fiore’s book.

Ian Davis: Right. And so he built out this curriculum. I’ve watched him. I’ve been in his classes and watched him take a bunch of people who’ve never done any kind of martial art in their life and get them able to deal with someone accosting them, like throwing punches, get into a grappling distance, work their way to a hook and tie, you know, take somebody’s back from that position, deploy a training handgun and shoot somebody. And he’s done this over the course of a day. So he’s kind of like Fiore, too. He travels. He travels all over the world constantly, he does civilian courses. He does military and letter agency courses where his job is to show up with.

Guy Windsor: So what is a letter agency.

Ian Davis: CIA, Department of Homeland Security. So DHS, like any of those acronyms.

Guy Windsor: Okay.

Ian Davis: And he comes into a disinterested population and tries to show them things in a very brief amount of time that will get them functional enough to, like, not die if things pop off. And that pretty well aligns in my mind with like Fiore bopping around training artillery militias and then Fiore, as super high level performance coach with some of the scariest names of his day. I think I’ve essentially just started using his curriculum at VA for our wrestling work.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So he’s not actually a Fioreist at all?

Ian Davis: Not at all.

Guy Windsor: He’s a reincarnation of Fiore.

Ian Davis: Yes, quite possibly.

Guy Windsor: Has he ever actually read? Have you shown him the manuscript?

Ian Davis: Yeah. The first time I emailed him, I was like, hey, did you know that you are doing exactly what a 15th century Italian knight said we should be doing? And he was like, What? And I showed him stuff. He uses tie ups. So if I’ve got one arm over hooked on somebody’s arm, I take their other arm and I shove it under and I grab both of their arms with one of my arms.

Guy Windsor: We see that in Fiore.

Ian Davis: It’s in the Stretto section. He uses something called a split seat belt. From that one I’ve got. And when I’m in remedy master, I push the arm back a little bit and I put my arm behind their body and lock down their arm. That’s called a split seat belt in modern wrestling. And that’s a really good position. I don’t have to worry about the arm that’s over my back and I’m tying up the other hand and I have a hand free so you can deploy that weapon. And that’s in Vadi. The split seat belt is in the first the first of the like hidden techniques that he doesn’t explain. You can see the hand coming through over the forearm.

Guy Windsor: Hang on a second. So which Vadi technique are we talking about?

Ian Davis: The first of the “here the play begins”. You know, the play is the set.

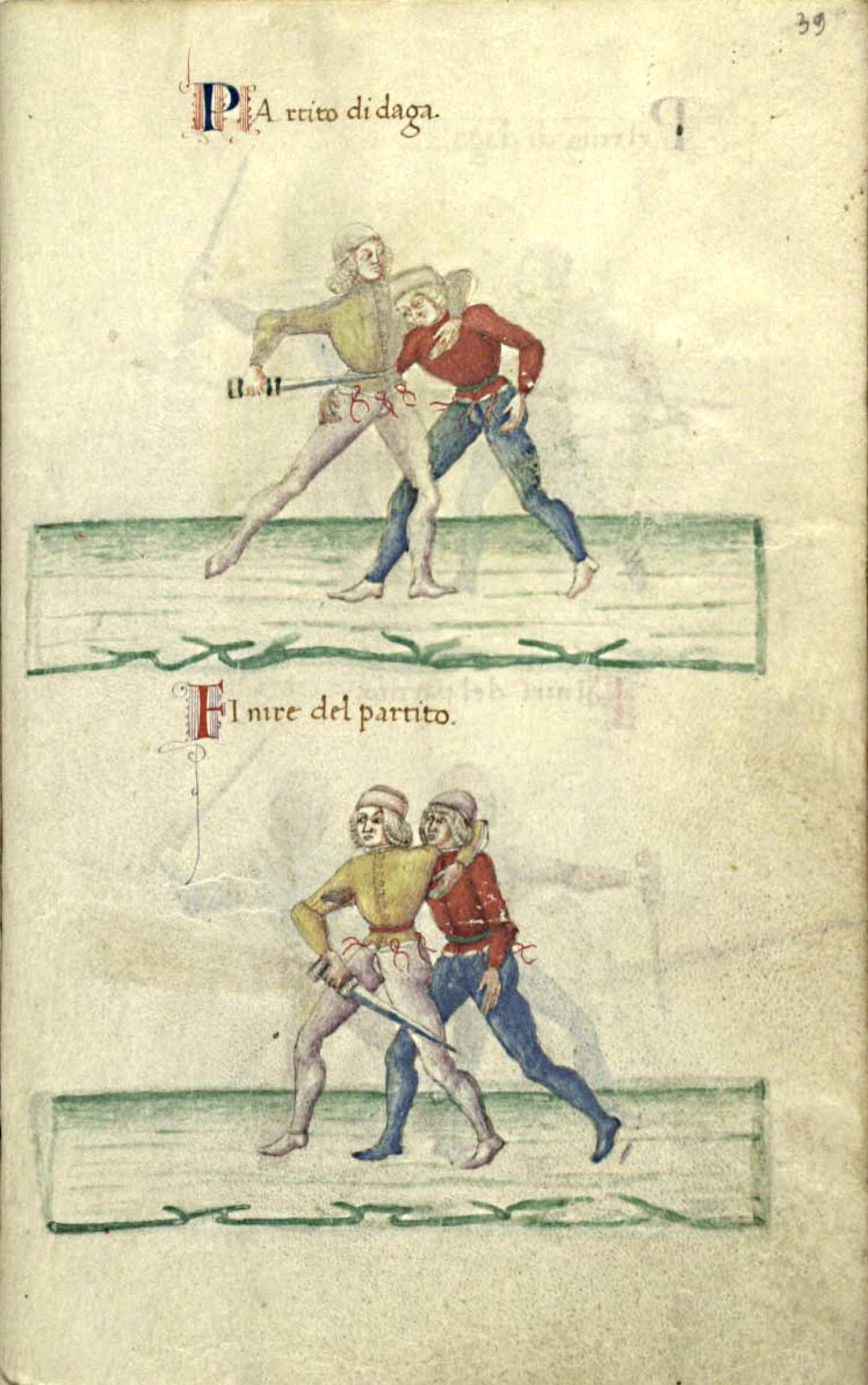

Guy Windsor: The section at the end. Partito di daga fineri del partito.

Ian Davis: Yes. A guy’s head locking him. See that hand coming through?

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So, he’s head locked.

Ian Davis: He posts up, he postures up, and he’s going to lock that hand down, holding the dagger, preventing it from being able to stab him. It’s not the end of the technique, but there you go. It’s a wonderful little tie up that prevents injury.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So we’re here, yeah?

Ian Davis: Yeah, the one on the right.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Okay. So the guy in the red jacket is reaching behind, and it looks like the guy in the headlock is grabbing the opponent’s hip.

Ian Davis: And then red shirt postures up, gets his hip sent under his head, and then that hand that he’s putting behind yellow shirt’s back is going over the front of the forearm. Now, of course, this is an interpretation, right? I’m interpreting it.

Guy Windsor: It makes sense because actually in the illustration, the red shirt chap’s hand is missing, you don’t see it grabbing the dagger. It should be over the top of the forearm. But you don’t actually see it.

Ian Davis: The it looks to me like the hand is coming out of there, like he’s in the process of reaching for it, to my eye.

Guy Windsor: You can’t actually see his hand at all, at least in the scans that I have. Anyway, I will put these pictures in the show notes. I’m not saying you’re wrong. I’m just making sure that I’m understanding what you’re saying. The problem with doing this over the internet is that we can’t just get up and have a go at it. Oh yeah. Okay, this makes sense. It’s a lot easier to discuss this stuff when you can actually hold the other person.

Ian Davis: Right. Actually, I pulled it up. It is just a dark spot. I view that dark spot on yellow shirt’s bicep to be the hand.

Guy Windsor: Oh, okay. All right. I will take a closer look. But anyway, so, so.

Ian Davis: So state of the art right now for modern combatives and self-defence involves playing this hook and tie game. Just a little bit ago there was a B.J.J. gym that has some Green Berets that train there. And they were talking about problems of room clearing and what happens when you walk through the door and somebody puts a hand on your rifle and presses it down into your body. And the solution that our trainer gives us is to dig an underhook on their left side, go to that shoulder and come down to a bicep tie on their right arm and drive them into a wall and hold them there and let your team member come help you out. Other things like that where more and more people are looking at wrestling as being arguably one of your best options for dealing with weapons, especially in enclosed environments.

Guy Windsor: Many, many moons ago, must have been about 2004, 2005, maybe, a friend of mine who used to work for the Finnish border guards, he had this seminar for his team and just for fun, we had a look at how Fiore’s armoured combat stuff, particularly the wrestling stuff, works against modern armour because of course these guys have sniper vests and festooned with pistols and batons and all that kind of stuff. And the wrestling plays. One of the things is that you don’t realise until you do it with someone who is carrying weapons on their belt. One of the things you are doing when you reach around and grab the hip and pull is you’re preventing them from accessing the weapon.

Ian Davis: Exactly. Right.

Guy Windsor: Right. And it’s just unfortunate that I didn’t illustrate the wrestlers as having daggers and swords and things strapped to themselves because it just makes a lot more sense when you have those things. And also the way the armour changes your centre of balance and changes what’s vulnerable and changes what you can grab on to. Fascinating. And it tracks actually pretty damn well to modern armour.

Ian Davis: Right? Like if we’re not talking about late 15th century, totally encased in steel, we’re looking at I’ve got a breastplate over a mail shirt and I may or may not even have leg harness. When we go look at Italians and what they were fighting in, there’s a lot of images where people just eschewed leg harness. There’s many congruencies between modern body armours and historical open faced helmets, right? Kettle rights and the like pseudo sallets. And there’s a guy, Michael don Vito. He’s done a lot of training for like tier one guys, like the people that are doing all the high risk stuff in the military. And he focuses heavily in on a grappling base for using the knife in close quarters because people can basically take lots and lots and lots of shots if those stabs aren’t hitting important enough things. Yeah, and it’s surprisingly hard to put a knife in important things when people don’t want you to. And so the best way to do that is to wrestle with them. And then you have them tied up in a way that lets you put the knife away, put it where you want it, which is grisly, but it’s also certainly Fiore’s context.

Guy Windsor: This is a point I have to make every time I teach people who are not familiar with historical martial arts. It’s this is not modern self-defence. This is absolutely no question, this is the military art of murdering the people you want to murder and not getting murdered yourself. But it’s not self-defence.

Ian Davis: You’ll go to jail.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And the context isn’t I am waiting for the attack because I am not wanting to fight. It is I have chosen as a tactical choice to make them commit to crossing into measure before I move, for whatever reason, or if I am attacking, I’m trying to murder the person and when they try to defend themselves I rightfully murder them in some in some other way. So how do you square the murderousness of a knightly combat system with the modern legalities and ethical issues of self-defence?

Ian Davis: Right. So Massachusetts you have an obligation to retreat in public spaces. So if I’m not attached to someone and I’m at a distance from them and I’m not in some way prevented from leaving the area, and I set up my denti di ghigaro and I wait for them to attack me. And I do my Rabat, my elbow press and I stick them in the neck. It’s murder, right? It’s just straight up. But when you start looking at crime statistics, most assaults that are a business transaction, robbery. Those begin in the 0 to 3 foot range. And they generally begin by ambush or by attachment. So you’re already wrestling in most self-defence situations, at least out in the public sphere, ignoring the other problems of a lot of crime, probably most, is actually committed by people you know, against you. And that’s where I think wrestling is much better generally as a former bouncer. If I repeatedly punch someone in the face to get them out of my bar, that’s going to be a problem. They go away. And now I have to talk to cops out front and demonstrate that I had a reason for using this level of force, etc., etc.. But if I grab somebody by the nape of their neck in their arm, I walk them out of the bar. You know, I say, go get Taco Bell, my guy. Like, stop. And that as a self-defence, having that wrestling facility is way more valuable than most things. So we’re probably wrestling in self-defence and there’s probably a weapon in play right? People attach to you and they threaten you with weapons and then that’s where we see, you know, fourth master, ninth master, fifth master, all of this, all of these aspects of the dagger can and should be used to deal with these problems because there’s like really elegant solutions. You know, if I grab behind somebody’s neck with my arm on the same side as the grab, that’s one way of attaching. I could grab somebody’s shirt and shove my fist up into their neck and kind of try to break their posture that way. I could reach across their body and frame them off of my weapon while I’m threatening them with it. If you go and you look at the solutions in Fiore things like cutting the arm down from above into the underhook, it solves all three of those problems with one action, right? Yeah. It’s a simple, elegant system. So there’s like specificity to it. There’s whole swaths of it that have zero use for modern self-defence. But there’s core pieces to the wrestling, to dealing with weapons in the clinch, that very much reflect the current reality and are really useful if you train them at a high enough intensity.

Guy Windsor: Okay. I have always steered the hell away from any kind of self-defence stuff. Firstly, because it’s not my interest and secondly because to my mind is that teaching self-defence it is primarily situational awareness and don’t get into the problem in the first place, right? If you actually have to use some kind of physical technique, then things have already gone horribly wrong and you have to react immediately at full throttle and then live with whatever the legal and moral consequences of that action are going to be. It’s just this hideous quagmire of downsides. Whereas, if we stick to the historical context, all that goes away, then the other thing with the self-defence stuff is the physical techniques of self-defence are boring. You use like one or two things, and you train them to be really, really good at them and you train to perform them immediately that you are triggered, right?

Ian Davis: I would disagree with that.

Guy Windsor: Really? Okay, go ahead.

Ian Davis: So Craig Douglas, the course I took with him was his ECQC course, which is basically I don’t concealed carry. I don’t even have a firearms license in Massachusetts because it’s just I don’t care. But I went there, I used a borrowed pistol.

Guy Windsor: What is ECQC?

Ian Davis: So extreme close quarters combat or extreme close quarters concepts. And so the first part of the whole course is MUC, which is, he’s a former military guy, so there’s got to be acronyms. It’s managing unknown contacts, which is basically learning the most important stage of any self-defence encounter, which is talking to people. And if you have the higher verbal agility you can develop, the easier it is to get out of whatever is occurring. If you’re not already in an ambush, then someone’s going to walk up to you and say something like, “Hey, man, you gotta light?”, and they’re going to close distance with you while you mess around with that. And then the attachment and all of those things are going to happen, right? How do you know in that moment, as someone is approaching you in benign conversation, how do you know it’s time to go?

Guy Windsor: Right.

Ian Davis: If my reaction is to like kick a guy in the groin and eye jab him immediately.

Guy Windsor: Then you belong in prison.

Ian Davis: Right? And he’s like, on the ground like, Oh, my God.

Guy Windsor: I just wanted a light!

Ian Davis: Yeah, I’m trying to get a smoke, man. What’s happening? So wrestling gives you a really low impact initiation into the self-defence problem, and it gives you a moment to think, Right? You dig that underhook, you tie that far side arm, you dig head position, and you get to assess for a second. You’ve stabilised the clench and you get to decide, oh, I smell alcohol. Okay. Is this guy just drunk? Is he digging in his pockets now? Oh, he’s hammered. All right. And then you snap him down and say, don’t get up and then walk away. Right. That’s a good legal self-defence use. Talking about the problem of edged weapons. Most people don’t know they’ve been stabbed until afterwards. Oh, he punched me. If your reaction to ‘we are now engaging in physical violence’ is to wrestle, stabilise the clinician, assess, then you’ve got to look at the hand and go, oh, that was not a punch. I see there’s a knife there. And I see that it has blood on it. Now the choices that you can legally make have just shifted.

Guy Windsor: But how do you train a person to be able to think rationally under that level of stress? Because if you’re not accustomed to that situation, which most people are not, how do you train the person to be able to actually have that level of detachment when presumably their pulse rate is up at about 200? And they’re at maximum stimulation.

Ian Davis: Stress inoculation. It’s the same thing you do for competitive wrestlers. So ramp up pressure over a long period of time.

Guy Windsor: You train people with stress inoculation? What do you use?

Ian Davis: Increasing stress levels.

Guy Windsor: But what do you use to generate that level?

Ian Davis: Competitive drilling. So we might start, for example, with some pummels. And then in the middle of that I shout, “Go!” And when I shout go, we have antithetical and mutually exclusive goals. My goal, for example, might be to take your back. Your goal is to stamp me to the ground. And then people just ramp up, right? The question is, how do we ramp people up into that level without injury and without having a negative training environment? And that’s one piece of it. The other piece of it is the evolutions that Craig does in his course. There’s a person, they’re not a bad guy yet, and they walk up to you and they start talking to you. And maybe there’s a shock knife in play. Maybe there’s a training pistol with sim rounds. You don’t want to get hit. It’s the closest we can get to mimicking that kind of stress and the uncertainty of that problem. You put the combatives helmets and you chat and you decide if this is a self-defence situation or not. And then afterwards you debrief. And it was really fascinating watching people do that because four people walked away from that course and said, I cannot concealed carry. I’m not going to do it from now on. They came in as somebody that carried a gun every day and they walked out of it saying, I can’t.

Guy Windsor: That is amazing.

Ian Davis: Yes, I think that’s because that’s the real problem. People do all sorts of goofy stuff for self-defence. And that’s where when I talk about trying to use some of this stuff for self-defence, there’s pieces of it I want to use. And then largely I want to follow the model of people who have been there and done that.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. When it comes to stress inoculation, I find doing things that are irrationally frightening. Like I can have a full on panic attack while bouldering because I’m scared of heights. Yeah, but the thing is, when I’m stuck on the wall, there ain’t nobody coming to rescue me and I have to get it under control and get myself down safely. And that’s that. If you want absolute terror, landing an aeroplane, a little light Cessna, not going very fast. And when you are maybe ten feet off the ground, a crosswind just flips your wing up and basically the plane starts to roll. Oh shit. And you have to just stabilise the plane and either do a go around or land the plane, depending on the situation. But you have to stay calm because if you panic and do what your brain wants to do is pull the stick back because the ground is the thing that is going to kill you. And if you pull your stick back, you’ll go up and away from the ground. But if you do that at that speed, you will stall and the plane will flip over to smack its nose into the ground.

Ian Davis: I didn’t know you piloted. That’s pretty cool.

Guy Windsor: I am about 33 flying hours into my aviation journey. Let’s see where it goes. It is like, really good for this little thing.

Ian Davis: So how do we create the wing flipping up in our wrestling practice? Right, exactly. I would say put people in a nice padded room and make sure they’ve got the headgear and the mouthguard and the cup and everything and then create antagonistic goals and then the wing is going to flip up.

Guy Windsor: Well, here’s a thought for you, I think if you and I were doing an exercise like that at some level, I know that your intentions are benign. And a large part of the stress of any personal combat is the social aspect. There’s a person who is trying to hurt me. It is much worse when it’s a person trying to hurt you than when it’s some random thing like a bacteria or natural disaster. It is just different in the human brain. And it just occurred to me that one useful thing would be maybe to have an arrangement with another club that does similar things. And you have to do this exercise with somebody you’ve never met before.

Ian Davis: And include, this is why I really like these evolutions that Craig does. You actually don’t know if you’re about to get into a fight. Somebody could walk up to you and really trying to be having a benign conversation with you. And if you react incorrectly. There was one that was really interesting where it was an older guy and it’s America. So I have to bring at least a little bit of race into it. It was an older white man and a young Asian man. And this younger Asian guy was covered in tattoos. I don’t think the older guy knew that, Christian was the younger Asian guy. Christian’s an NYPD cop, actually, but he was just going to walk past this guy. He just got it in his head. I’m not even going to address him. I’m just going to walk past him. And the guy engaged him in conversation and said, “I need you to back away.” And Christian turned to him like, what? And then the guy just immediately “Back the F’ up!” Like screams it at him and then tries to pull on him. Everything about this is like the worst possible self defence.

Guy Windsor: The worst possible reaction. It’s just a guy walking past you.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And Christian gets on him, wrestles him to the ground, gets the gun out, throws it across the thing, and then, you know, fake pulls his cell phone out and was like, this crazy dude just tried to pull a gun on me and right after you debrief it. So that’s the question of like violence is always socially mediated and it was definitely socially mediated in Fiore’s time too, there’s all sorts of laws and stuff. So I think there is, you know, why a wrestling base, right? Why not just pull your sword out and kill a guy? Because maybe vendetta.

Guy Windsor: But also if you have armour and a lot of people wear armour a lot of the time. Then pulling out a sword and killing the guy, you’re going to have to wrestle them anyway. Right?

Ian Davis: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. I mean, Fiore is explicit that wrestling is the foundation and I don’t think he was wrong. It’s just interesting to me that it seems to be coming full circle because wrestling certainly wasn’t considered the foundation of martial arts and self-defence in the eighties and nineties. Then it was all kicks and punches.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And then I think enough legal cases probably happened where Craig does use the eye jab and when we’re talking and I’ve got my hands up and he gives some criteria for what he calls pre assault cues, the final stage of that being a definitive weight shift someone puts their weight on their back foot because they’re about to launch that big right hand. And if I see that, legally I don’t have to wait to eat the punch before I can defend myself. And what he recommends is basically hold a tennis ball and stick the tennis ball in their face at high speed. And if we get like a corneal abrasion on the person and can run, then when we go to court about this, because we’re probably going to court about it, if it’s a he said she said, the defendant’s sitting there with a little eyepatch on. But if I went full Krav Maga and you know, and beat this dude up.

Guy Windsor: But is this an imaginary tennis ball or a real one?

Ian Davis: Yeah, it’s imaginary. It’s just a way of arching your hand. It’s actually, if you look at I think the Getty guard of porta di ferro has this awkward finger arch, it’s like he’s doing a little monster claws. And I always found that really interesting. Check it out.

Guy Windsor: It shouldn’t take me this long to put my hand on the truth. So we’re talking about…

Ian Davis: …the abrazare guard of porta di ferro. I think is, if I’m remembering correctly.

Guy Windsor: Oh yeah. His right hand is splayed.

Ian Davis: Yeah, it’s splayed and the fingers are arched. I find that like an interesting little detail to include.

Guy Windsor: It’s true in all of the guards. The backhand in posta longa, the backhand in denti di ghigaro, the right hand in porta di ferro, and arguably both hands in frontale.

Ian Davis: That’s interesting. I’d only ever noticed it in porta di ferro. So anyway, all that to say like the ‘it’s go time’ argument for self-defence I don’t actually agree with, because that presents a situation where you’re going to get in legal trouble or it could. Versus a wrestling base and the idea that you’re going to establish a dominant position and control and then assess what needs to happen.

Guy Windsor: But does not that require you, particularly if you’re smaller than your opponent and all wrestling competitions have weight classes. So how does your wrestling base help you if the other person has 50lb on you?

Ian Davis: Very well. Annette, one of the people that regularly comes to Stretto Sunday, she’s about 130, 140lb. She’s thrown a guy more than twice her weight.

Guy Windsor: Oh sure.

Ian Davis: It wasn’t a lift and throw. It was proper use of posture and position and getting around.

Guy Windsor: Absolutely. But that was that was in the salle, surely.

Ian Davis: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: How would that track against somebody holding a gun?

Ian Davis: I thought Sarah at SCQC where we started on the ground I had top position and she, I would guess she was from a Krav club, weighs maybe 165, something like that. And she had some BJJ background and so we were wrestling, we started out in top and bottom position. She’s got a hand on my trainer, I’ve got a hand on hers and we’re going to wrestle until somebody can get a shot off on the other person.

Guy Windsor: So by trainer you mean training gun?

Ian Davis: A training gun, yeah. And we went after it. I used a shin staple, I pushed her hand to the ground and I drove my shin over her hand, pinned her gun to the ground, pulled mine up, but she had enough of a hand on it. She pushed it out of battery. And then I yank it back, I rack it off of my hip, and I cause a double feed malfunction. So I’ve got two cartridges stuck in the slide. And she just kept her head calm and she was like, okay, he’s on this. She set her hips upright. She crunched her whole body in, and when she exploded her legs out, she ripped her hand out from under my leg, she got a click because I’d already put her out a battery. She tapped rack and then strung me up with it. Absolutely lit me up. So did I have severe dominance for a lot of that? Yeah. If I didn’t have a double feed malfunction, would she have “walked away from that”? Probably not. But it happens in the real world. And I forget which manuscript it is, but one of them says that the art gives the smaller man a chance.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, I think that’s fair. And of course, weapons reduce the problem of weight.

Ian Davis: Right. It doesn’t matter how strong a muscle is, if it’s no longer attached to the bone.

Guy Windsor: Right.

Ian Davis: And that’s where edge tools are get off me tools.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So obviously, I am thrilled anytime Fiore is found to be relevant because I’m a Fiore man through and through. I’m just curious as to are there no more directly relevant written sources that you could be using? Like, I’m thinking for example of Sykes Fairbairn, and their World War II Combatants, for example.

Ian Davis: For my money, I don’t think you can beat wrestling. And I think that the Italian methodology of wrestling assumes weapons are in play. That’s why like, for example, Pedro Monte wrestles from a two on one. He’s got foot sweeps and things where we’re both binding up each other’s arms and we’re using foot sweeps. I don’t want to spend most of my time doing, quote, “reality based combatives”. I don’t think they actually prepare you very well versus thousands of hours of fun, exciting, interesting, resistive training that periodically goes up to really high intensity. And then we bring it back down and get lots of good training reps in. I think there’s a day coming. Right now I’m a financial counsellor and I work at a non-profit. The day is coming where I try to transition into martial arts entirely and there will definitely be a hard line between, I’m going to have a historical program and I’m going to have a modern combatives program, and there will be a very hard line between those two things.

Guy Windsor: Sensible.

Ian Davis: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: So you say you want to do this for a living?

Ian Davis: Ideally, yeah.

Guy Windsor: Ha. Well, okay. I have some advice for you.

Ian Davis: Yeah, I would love to hear it. You’re the blueprint.

Guy Windsor: Don’t get addicted to a regular income. Because it is seriously erratic, and it always has been. So that’s my advice.

Ian Davis: That’s good to know.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, but when the day gets closer if you want to just have a word. We can have a chat about some of the specifics. Happy to help because this has been my job since 2001.

Ian Davis: But I think there’s no point in reinventing the wheel is really my big argument.

Guy Windsor: Sure.

Ian Davis: I do not condone this man. I’m about to give a quote from this man, but I think he’s probably a bad person. So let me preface with that. He’s a big guy in the self-defence industry, Dave Grossman.

Guy Windsor: Oh, right. I’ve quoted him in several places. Is he not a nice person. Okay?

Ian Davis: Do a little research into him. It depends on your perspective. I personally don’t like a lot of the things I’ve read.

Guy Windsor: So there’s this massive background noise, some bells and jingles. Go again.

Ian Davis: There’s this quote from him that is the self defence industry is full of a lot of virgins talking about sex.

Guy Windsor: That’s very true.

Ian Davis: Yeah. And I’ve had a number of violent encounters in my life. Unfortunately, a lot of those were family, which is why I bring that perspective into when I talk about self-defence. But there’s a lot of other pieces of violent encounters that I’ve never had any experience with, and I have no desire to try to talk myself up like I have. I’m not going to try to invent a back story, so I can take the experience of guys like Craig Douglas and I can look further back. I don’t need to just stick to people that I can currently talk to. I can go what are the realities that Pietro Monte is discussing? What are the realities that Fiore is advocating? Pagano, all these guys, like they did it, and there are lessons we can learn from that.

Guy Windsor: I have no interest in modern people’s interpretations of swordsmanship, right? None, because unless you’ve actually survived somebody trying to murder you with a big sword. Or have taught people to survive somebody tried to murder them with a big sword, and they have successfully done the thing. Then I don’t think there’s any real basis for saying this is going to work because it’s never actually been tested in reality. Whereas Fiore’s stuff, there’s no doubt that he was highly respected in his time. Right. Take Formula One, for example, if a Formula One world champion says that guy can really drive, you take their opinion seriously. And everyone in his period was saying that Fiore could really drive. So, yeah, when I’m teaching longsword, for instance, no one should have any interest in Guy’s longsword, right? Because Guy has never had a sword fight. Not a real one. But I’m trying to bring them Fiore’s longsword stuff because that should actually work. That’s the problem that we have. I don’t know if you’re quoting him correctly or not, but that’s attributed to him anyway. Virgins talking about sex. We see that a lot in the historical martial arts world, too. Where people are taking on something that works for them in the tournament and saying, well, then this must be what this was in the book. And actually, the tournament situation, the modern 21st century tournament situation, is nothing like any context that anyone ever experienced in the period that we’re talking about.

Ian Davis: Yeah. The hallmark for me, is I’m going to quote Craig a lot. Current he’s the guy for me.

Guy Windsor: Clearly, he’s your guru right now.

Ian Davis: This is a guy who has been there and done that. He was robbed at gunpoint nine times.

Guy Windsor: When the hell does he go that he gets robbed at gunpoint nine times? That’s ridiculous behaviour.

Ian Davis: Buying drugs from bad people as part of his job.

Guy Windsor: Oh, it’s part of his job. Fine.

Ian Davis: And he talks about, like, the worst part of this, right? He’s not an addict. He’s mimicking the behaviour of addicts. He goes to do a drug buy, somebody sticks a gun in his face and takes the money and is like, come back tomorrow and I might sell to you. And he has to go back to next day because they didn’t get the guy on camera or whatever and he has to get robbed and then he has to go back to the guy. But that’s what people in that market actually do. So that’s how. He’s not like one of the guys that’s like “I’ve been in a hundred street fights”, you know. It was a part of his job and he pulled out some commonalities of that. But what he talks about is you need congruent, minimalist, reductionist systems. And when we start going in, we look at like combatants manuals from World War Two or where it was used and designed by people who used it. Or we look at like Craig’s curriculum, or we look at Fiore, there’s like six things. There’s like six things, and he’s going to show you like a hundred different ways to apply them.

Guy Windsor: Just define those terms though. ‘Congruent’. What do you mean by that?