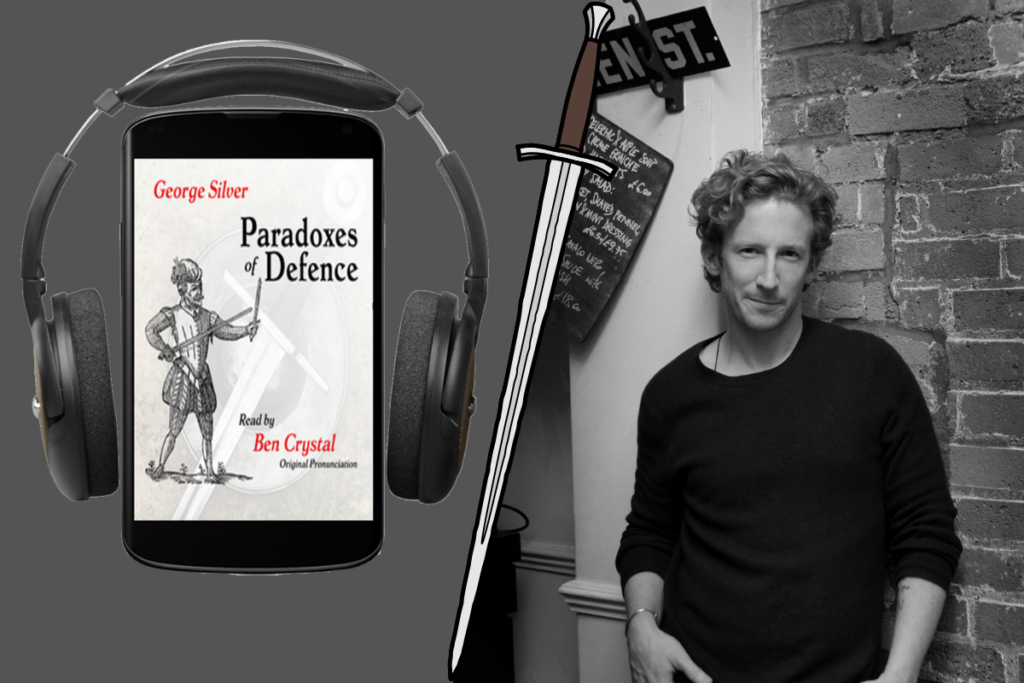

GW: Hello, sword people, I’m here today with Ben Crystal, actor, author and creative producer. I first met Ben when we worked together on the George Silver audio book, and Ben is well known as an explorer of original practises in the theatre. He’s possibly best known for original pronunciation, which is, of course, what I hired him to do for the George Silver audiobook. But as you will hear in the interview coming up, it goes way beyond just how you talk. So without further ado, Ben, welcome to the show.

BC: Thanks so much, Guy. It’s great to be here with you.

GW: So whereabouts in the world are you?

BC: I’m currently on the Isle of Anglesey, North Wales, where I’ve been for much of the last 14, 15 months or so.

GW: OK, the Isle of Anglesey in North Wales, I imagine that’s very beautiful and rather remote.

BC: It is both of those things. I think the only thing I could have castigated it with before the last couple of years was that it’s very isolated and have been very grateful for that in the last one year, 2020 at least. It’s just off the north west of Wales, linked to the main land of the UK by two bridges and a beautiful land.

GW: And naturally socially isolated.

BC: There’s a lot of good coast here, that’s for sure.

GW: Fantastic. So how did you get into this line of work, acting and original pronunciation and that sort of thing?

BC: Well, I started out like many Shakespeareans, because I should say that I’ve really been working with Shakespeare for most of my adult life, hating Shakespeare in school. And it wasn’t until I acted in a Shakespeare play for the first time at 17 or so that the world really broke open to me. It made sense for the first time in my life in a way, on a stage, in a way that it’d never done, just reading in a book and especially in a classroom. And I never looked back. And that was the point when I wanted to be an actor and I spent most of my time in university dodging my degree and spending all of my time in the theatre on campus in Lancaster University, and then came down to London for a sort of Masters, a postgraduate year in acting at the Drama Studio London. And that was where I was taught by Patrick Tucker, whose work with exploring the secrets, as he calls it, of the First Folio. This is the first major edition of Shakespeare’s plays that was published seven years after his death. And Patrick taught that these plays are actors’ manuals that teach his actors, who had very little rehearsal time, how to not just perform, but how to stage these plays. And that was the beginning of my fascination with historically inspired performance, I suppose you could say. The other way of putting it would be original practises. And of course, this was just as the Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre was opening in the south bank of the River Thames in London. So there was quite a renaissance, I suppose, of explorations in original practises because of course, Shakespeare’s Globe is an original practise exploration or experiment in architecture. And then within that building, they started to do all sorts of explorations in terms of costume and music and of course, fights and latterly started to explore original pronunciation. My father was invited to lead those explorations, and I wasn’t so interested in the sound itself until he came back from rehearsals one day and said that the Master of Movement had come in and sat down next to them and they were rehearsing Romeo and Juliet. But they’d been rehearsing in received pronunciation.

GW: Posh English.

BC: Which is the standard for doing Shakespeare in the 20th century. And they were just doing three performances in original pronunciation. And she came in for the first go in OP and said, my goodness, they’re moving differently. And that’s what got my attention, because I’d seen so much Shakespeare in RP, in received pronunciation, where everyone was standing very stiffly and speaking this beautiful sound but not moving like human beings. And I spent a lot of time with Théâtre de Complicité, doing workshops and lots of physical work, Lecoq based stuff from the Lecoq school in Paris, and they would move beautifully but weren’t so great actively with their voices. So aside from fight work, where does the two come together? And the idea that this accent, this original accent, was fusing movement and sound in a way that was new. That’s when I really got on board with the historically inspired performance, or original practises.

GW: Right, and OK, just going back a little bit to Shakespeare in school, reading a Shakespeare play in like an Arden edition, one of these modern editions, to me, it’s a bit like studying animals by looking at their DNA. You don’t get a sense of what an elephant swinging its trunk around is really like by sequencing its DNA.

BC: Absolutely.

GW: And my degree’s in English Lit. So I’m used to reading all sorts of different kinds of text, but I always hated reading plays. Some bits of it will work as poetry. But just sitting and reading a play to me always felt dead on the page.

BC: I completely agree. And I think apart from a very few select band of folks who were able to read in Shakespeare’s time, I think it was very much the same for them. I wrote a book shortly after working at the Globe in 2009 called Shakespeare on Toast, saying that reading a play may seem a little bit more normal to many of us out here in this century, but we wouldn’t read an episode of Coronation Street. Why would you, having seen it, and to a degree that was true for the Elizabethans and Jacobins. But your elephant analogy I transposed to a car analogy: would you rather be handed the engine manual to a Ferrari, or would you like to drive it? Would you like to read the recipe of a great meal, or would you like to be taken to the restaurant? Would you like to read the score of Mozart’s Requiem, or would you like to sit and hear it live? Why would you want to interact with a thing that’s written for a very select group of very well craft-fuelled men, because women weren’t allowed to act in Shakespeare’s time, that were singularly skilled in interpreting these pieces and knew, as it were, as Patrick Tucker suggested, the colour coded map that’s written into these works for them to sort of say, oh, he wants us to do this at this point. Without that key, without that experience, without any sort of the ten thousand hours that comes with craft, whether it’s reading a musical score or a food recipe or an engine menu, you’re not going to get a sense of, to come back to your analogy, how that trunk swings and what the smells smell like and what the beast feels like when you put your hand on it and feel its heart beating. I think it’s the same with plays, of course, especially with these plays that that are so rich and full of human life, which is, of course, is one of his primary skills as a playwright.

GW: So I imagine that this study of how the language was spoken led you to change your interpretation of some of the passages.

BC: Yes, in ways that I couldn’t possibly have anticipated. There are some obvious ways in that one of the ways we know what the accent sounds like or sounded like is from the rhymes. Two thirds of Shakespeare’s sonnets don’t rhyme anymore. If you know very much about sonnets, they’re written in alternating rhyme structures, finishing with a rhyming couplet. And yet two thirds of them don’t rhyme in a modern accent, in modern received pronunciation accent, anyway, the standard accent that people expect Shakespeare to be spoken. And so something’s changed, right? Or Shakespeare was a bad poet. That’s probably not so likely.

GW: Yeah. I remember coming across this problem when I was studying Shakespeare long ago. Like “proved” and “loved”. That’s not a rhyme.

BC: Well, absolutely. And so, you know, linguists like my father would look at these half rhymes or failed rhymes and go, well, chances are it would have either have been prooved and looved or proved and loved. And you go through the rest of the canon and work out that it’s very likely the latter rather than the former. And that’s one of the ways that we know what it sounded like. So it was a great joy to get to the end of a sonnet, having rhymed beautifully all the way through, and then it to end with a lovely rhyme or looking at one of the rhyming plays like Midsummer Night’s Dream or Richard II. I think of it a little bit like I imagine a master watchmaker or something. You know, the satisfaction when you just click that last bit of cog into place and everything starts running beautifully. There’s an inherent rhythm. And I’m very aware of the fight analogies here. But when things are clicking well, there’s a roll that that you can feel. And without those bumpy obstacles in the way there is a slide, as it were, to slip down. When you’re speaking the verse, when you’re speaking the poetry, that those rhymes really help. That was really nice. But then there were other things. I was invited by the British Library. They were doing an exhibition where they had one of the first editions of Richard III underneath this glass cage and a spotlight on it. It was open to that opening speech, “Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this son of York.” And the idea was that you could go up to the book and put the headphones on and hear the speech spoken in the original accent. So of course I said yes because it was I was in my late 20s, early 30s. At that point, I thought, wow, I’m never going to get to play Richard III. Of course I’ll go and do it. I start doing the speech, having run it by my dad a few times to make sure that I was in the ballpark of the sound. And halfway through, you get to this line where Richard said says, “I am curtailed by this fair proportion, cheated a feature by dissembling nature.” And it’s such a powerful line. Because Richard feels that the world or “Nature” with a capital N has been unfair to him cheating him of a fair proportion and cheating him of regular looking features. And you could argue that that’s his soul. That’s the crux of the thing that drives him, or at least the crux of his life that’s pushed him to this place. One of them, anyway. Now in received pronunciation it is cheated of feature by dissembling nature. I mean, my voice is modified received pronunciation, but in an original pronunciation it goes, “I who have been curtailed by this fair proportion cheated a feature by dissembling nature.” And all of a sudden the hairs on the back of my arms went up and everyone else’s in the room because the rhythm suddenly canters, it ratchets up a notch because of the nature of those short vowels all slipping together like that. So it was the first time we realised, my goodness, we know that Shakespeare explores rhymes with this sound and we know that he makes puns with this sound that are lost. And I don’t think anyone quite appreciated that he was also mucking about with the rhythm of the poetry too. And I think that was a real another real eye opener and game changer for me. Just the degree to which these explorations in how it was done can open up new pathways for the way we think about these works and how we can do these original practises, these historically inspired explorations, they really can offer bridges to the future, not just dead ends to the past, I think.

GW: Right, and of course, I’m listening to all this and filtering it through my historical swordsmanship filter because literally everything is filtered through swords and I have many times come across these similar moments where things just click into place and suddenly things that were difficult become easy. And that’s not proof that the interpretation is correct, but it is a whole lot of corroborating evidence to suggest that it might be.

BC: Yes. I don’t know if you feel this, too, but you’re in practise, you’re in play, you’re exploring with likeminded folk who have similar degrees of experience and skill sets and interest. And you discover something in that moment of play. And neither were expecting, neither were planning and almost feeling like you’ve stumbled onto a… I don’t know… Let’s swing to Indiana Jones here, onto a rock or a lever or something. A handle that you think was completely innocuous and you’ve just pushed it and it’s opened up this whole new idea and you feel, oh, we’re not discovering something new. We’re discovering something old here.

GW: And you get a sense of the life of the thing as it was done.

BC: Yes, absolutely. Absolutely.

GW: So we talked a little bit about original pronunciation, but that is just the tip of the historically inspired performance iceberg. So I know absolutely nothing about historical staging of Elizabethan theatre, and I’m guessing that most of the listeners know nothing about it either. So what else do you do in the theatre to recreate performances as they may have been done?

BC: Well, let’s start with the Shakespeare’s Globe Theatres on the side of the River Thames, where we’ve got an outdoor theatre and an indoor theatre that have been, as best as budget and understanding has allowed, designed architecturally to mirror as close as possible the dynamics of four hundred years ago. And I’ll come back to the point that most of us practitioners don’t have access to that kind of space. But in a very broad sense, the outdoor space has a couple of dynamics which really change the way that you play and perform and produce. Insofar as the outdoor space has no roof, when they perform in the evening time, they mimic the lighting to replicate daylight. That means that contrary to 20th and 21st century standard theatre Shakespeare experience, where the audience sits in the dark and the actors stand lit on the stage and act into the gloom, there’s a shared light, which means that if I come out as Hamlet, I can see you standing there or sitting there in front of me. I can see you whether you’re happy or sad or enjoying yourself or distracted or bored or sleeping or texting. And I can talk to you and I can say to you, as Hamlet, what do you think I should do? Do you think I should kill Claudius? And ideally, hopefully you’ll be so into the story and with me, the protagonist, that I might even provoke you to respond. And there’s actually a dialogue between us, as storyteller and storytellee. We’re on a journey together. Because there’s more of a symbiotic relationship. You’re more likely to laugh when I make a joke and you’re more likely to cry when I die.

GW: It is closer to panto in a way, as there’s an interaction, the expected interaction with the audience.

BC: And I should say that we’re not and we never will be sure about the level of realism that they were performing at four hundred years ago. And some people say that some of the back and forthness that is written into the texts as well, I should say, at least in this country, one of the closest parallels we have is pantomime. But I think that’s where it stops in terms of that symbiotic back and forth or in terms of that dialogue that’s encouraged. And from what we can tell, the levels of realism were as profound as we imagine them to be, rather than up into the heights of slapstick and ridiculousness, although there was certainly both of those things at the time, too. So you’ve got this shared light and you’ve got this journey that we’re all going on together. You’ve also got the two pillars that hold up the roof of the stage. So there’s a roof above the stage, but not above the rest of the groundlings, the people standing around the stage. And those pillars mean that there’s no one place on the globe stage where you can be seen by every member of the audience all the time. But what they also inspire is a sort of figure of eight eternity symbol in that as you walk around the pillars and across the centre of them and back around the other side of the pillar and back across the centre, you transcribe this figure of eight in your movement that allows everybody to see you and for you to see them. And having done that, you can take the God spot at the centre, it’s not quite the centre, but the main strongest part of the stage. And the audience get the impression of being able to see you even if they can’t quite. There’s a movement quality that comes out of that sort of architecture, but of course, that’s still our twentieth, twenty first century heads wanting to be seen or indeed as audience members wanting to see, whereas Shakespeare’s audience was said to go and hear a play rather than see a play. To hear what was going on. And that’s where the word “audience” comes from. They would audit a play. So there’s a shift in understanding. There might be a bit of a pushback, both either by directors building the stage out into the yard and wanting everyone to be seen, but listening to the true nature of the building and sitting comfortably in that place, both as performers and as audience members, that sight is not as important as sound is quite a twist for our modern heads. But I think the listening is the really key thing. And again, that sort of tacks onto the point I was about to make earlier about what happens if you don’t have access to that kind of space. But then the other space that they have is an indoor space. It’s closely modelled on the Blackfriars Theatre that Shakespeare wrote his late plays for plays like The Tempest and Winter’s Tale and Cymbeline. It’s candle lit. And for anyone that has ever read a bedtime story by candlelight, the hush, the atmosphere, the sleepiness, the way that the eyes work differently, even with a full complement of candles, there’s a diffuse quality that comes with candlelight that inspires shiny costume and sharper eye makeup and a different quality of hand movement. Also, if you’re using practicals, if you’re holding a candle, let’s say you’re in the middle of Macbeth’s house in the middle of night and you’ve just killed Duncan and all the candles are out apart from the one that you’re carrying, then you also become your own lighting designer. So there’s all sorts of really interesting qualities that come out by exploring just these two very basic different dynamics in the way that Shakespeare and his company acted 400 years ago. Now, let’s say you don’t have access to those spaces. And I founded the Shakespeare Ensemble and we go around the world performing Shakespeare, using these modern adaptations of original practises. We have performed in some very beautiful old buildings and theatres in Japan. Most of the time our work is community based and we go to somewhere that has never heard Shakespeare before. And we listen to the environment that we’re in and we respond to the things that are important to them, I suppose, or at least to the resonances that we pick up from the cultures we find ourselves in. And I think that listening thing is the key. You’ve got 16 actors 400 years ago that spend all day, every day working with each other, with the same playwright in the same spaces and come and go, to a degree, the same audiences. They didn’t rehearse very much, nor did they need to because they were so good at listening to each other, to each other’s play, to the audience, to their master’s voice.

GW: Like a jazz band.

BC: Exactly so and I think the best modern original practise explorations are the ones that listen to the world around them. So, for example, women weren’t allowed to act in Shakespeare’s time. Well, we changed that so anyone of any gender can work in an original practises with us. We do use cue scripts in that we don’t each hold a copy of the play. We only hold the parts that we’re exploring like a modern orchestra.

GW: And that’s how they used to do it.

BC: That’s exactly how they used to do it. In fact, some of Shakespeare’s plays were reassembled. There weren’t full copies of the play to be able to be published. So they had to reassemble them from actors’ cue parts that they collected and put together back again like a jigsaw puzzle. And then we look at some of the old sketches of which there aren’t very many of them. There’s an old sketch of Titus Andronicus. And it’s confusing to a lot of scholars because you’ve got actors standing around in Elizabethan costume, you’ve got other actors standing around in Greek costume, and you sort of get the impression that putting together a show was a degree of grab whatever you can to help tell the story, whatever works. And so we also work with very few props and costumes, just enough to tell the story. We’re usually rocking up in whatever we’re wearing that day, and I suppose without the resources of a massive theatre, historically inspired performance or modern original practise performance is for me anyway, about listening to your environment, listening to each other, and taking the resonances and echoes that are tangible in terms of grab whatever you can to help tell the story the best way you can, but don’t fill it with things that you don’t need. You don’t need a huge costume budget. You don’t need a huge set budget. What you need is brilliant wordsmiths who can activate and fire the imagination of the people listening, even if they don’t speak the language that you speak. One of the comments that we had from a mountain community in Japan was we didn’t understand 99 percent of what you said, but we fully understood the story because communication of heart is your craft. And I think that’s the core. That’s the core of what Shakespeare and his crew were about. We love these beautiful new buildings because we don’t build stuff like that anymore. But whilst the building was important to them, it was a space in which that that very simple craft was communication of heart, inspiring and provoking imagination.

GW: Right. I was just thinking about Midsummer Night’s Dream. You have the group of players. And they are practising in a wood somewhere. They’re not practising in some fancy rehearsal hall with mikes and lights that they’re just basically doing it in the forest.

BC: Exactly. And actually, that’s one of two instances of rehearsal in Shakespeare’s plays. And some people try and take it quite literally. There’s a scholar that worked out the time frame of the hours available to Shakespeare’s actors, and they perform every afternoon around two o’clock, best sunlight until about four or five, depending on the length of the play. You don’t want to be performing that much longer because it’s getting darker. But also people have been standing and people’s attention spans, all that kind of thing, and then clean up, sort the play out for the next day, go to the tavern, go and be with your family, whatever. Get there the next morning. And what are you going to rehearse? Are you going to rehearse the dialogue bits? Well, Richard and Cuthbert know their stuff, so we don’t need to rehearse that stuff. Are you going to rehearse the speeches? Well, that’s the actor’s part, right? They know that, they don’t need to rehearse that. So what do you rehearse? The idea is that they probably just rehearse the complicated bits, which would either be the scenes where there’s a lot of people moving around and you want to make sure you’re not going to bump into each other like the lobby scene after Duncan’s been killed in Macbeth and everyone comes out and wakes up and rings the bell and lots of entrances and exits, that sort of thing. You’re going to rehearse the dances, perhaps, if you want to create a new dance or a fresh one, because you haven’t done the play in a while and you’re probably going to look at the fights.

GW: Yes. My next question was going to be, OK, this is all great and fascinating and lovely. And I know a whole bunch of people are going to be super excited about this, but we do have to get to the swordfights eventually.

BC: Exactly so.

GW: All right. So tell us about the fights.

BC: Well, again, I’m going to piece this together from what little we know and what we’ve explored. The anecdote that’s very common and very likely is, we haven’t got much time, we’re all pretty good at waving a stick around. And, of course, as you and I joked about when we first met, the main difference between what you do and what we do, is we try and miss.

GW: Yeah.

BC: And what I understand anyway, a lot of your folk are trying to hit more. But notwithstanding that slight distinction, let’s say you’re doing the new play. We haven’t got much time. Let’s take a bit of Mercutio and Tybalt and let’s take a bit of, I don’t know, some other rapier…

GW: Hamlet and Laertes?

BC: Exactly, a bit of Hamlet and Laertes. And we’ll tack on a new ending and we’ve got ourselves a new fight. There is a very good chance they would have been able to piece together new fights from old.

GW: I’ve put on fights for various events many times. And when I’m using my students, we can choreograph a minute long sword fight in about five minutes by just tacking together drills that they already know. And we work on the opening and we work on the ending. And the middle bit is padding, which is basically just drills repeated.

BC: Perfect.

GW: It is super simple and it takes minutes. And everyone who studies with me, seeing that fight, will recognise the bits. Most people I don’t study with in the event is for some company or some theatre or whatever. And the audience, they have no idea, they’re seeing it for the first time. And they would be like, oh, that was cool. The end was great. And that’s what we’re looking for.

BC: And I imagine because that middle bit is padding or drills, as you say, that there’s a degree of playfulness and an unrehearsed, sort of fresh, raw quality. So we’ve taken a little step beyond that in that all good actors in stage combat with rapiers of sorts have been trained or practised in their one, two, three, four, five, six, reverse six, whatever, however you refer to it. So if we know what we’re going to start with and we know what we’re going to finish with and we’re listening to each other so well because we’ve been playing together for ten years every day, then to what degree within the one to seven, can we just play and it be improvised? Now, of course, you know the golden rule of modern stage combat is you do not improvise away from the choreography. But then of course if you’ve choreographed, then there’s an expectation of what comes next. But if you’re playing, then you just play, right? It’s really simple. So I think that’s been the most exciting stuff that we’ve done is, is when the play that happens in the fights mirrors the play, because all of our movement is improvised. We never block a show. There’s no time to, we just listen to the architecture and listen to each other and play in the space around a sequence of set ideas of movement in terms of if there’s two of you then you take turns in the God spot, if there’s three of you start making triangles and so on and so forth, so that there are soft guidelines rather than rules within the movement at play. And when we explored fights in a similar way, it really works. It works really well.

GW: Yeah, it works really well when you’ve fenced with each other many times. And I have also choreographed fights where we choreograph the beginning and choreograph the end and in the middle we just fence, but know that we’re not supposed to hit each other. So fence at a level where you know that your partner is going to be able to make the parry, because if you hit them then that’s the end of the fight. And that’s not the choreographed ending. And then we have a signal between the blades to say, OK, now we go into the final bit.

BC: Perfect, beautiful, and we’ll never know, but from everything that I’ve learnt about how Shakespeare and his crew worked and as I keep saying, the time constraints that really seems to resonate with what we understand in the early modern practise.

GW: We they using stage swords, like blunted foils or what have you?

BC: We don’t know. But of course he wrote different types of fights. Edgar and Edmund’s fight at the end of Lear is broadsword rather than rapier.

GW: Good old English stuff. Silver would be proud.

BC: Absolutely. Yeah, well, absolutely. I think just not to pre-empt any bridging here, some of the most joyful bits of reading Silver, were the ones that resonated and echoed with comments, especially by Mercutio in Rome and Juliet, about preferences towards different types of fight.

GW: OK, well, by all means, please be specific. So my next question would be, what do you think of Silver’s Paradoxes? Now that you’ve read the whole thing out loud into a microphone. You can be one hundred per cent honest. If you don’t like the book, that’s perfectly OK. But I’m very curious to see what you thought of it and whatever that means to you.

BC: A lot of different feelings. I loved it. I loved reading it. What a pedant. So similar to so many authors of the time that published these pamphlets that were essentially soapboxes of one kind or another. The difference, I think, is because, of course, one of the first references to Shakespeare was by a pamphleteer pedant that was railing about all sorts of things, but included a rail about the “upstart crow William Shake-scene”, seen in Shakespeare’s very early career. But the difference, I think, is that Silver, he’s the craftsman. He knows his stuff. And I think the harder bits to read were the bits where he’s really getting into fine detail, going off on one, and forgets to break things down into sentences. And there’s a degree of an artistic interpretation there. Do you try to make that make more sense, or do you try to allow that to be as it was written in that it may not make complete sense because quite frankly, there were bits where he could have tightened it up and edited it down.

GW: He didn’t have a great editor but pretty much nobody back then did.

BC: Well, absolutely. And yet there were times when his flow is extraordinary and not to take my own name in vain, but crystal clear. And I think that’s true within some of his descriptions of technique, although I think my very favourite bit is his story at the end where it’s like he takes the leash off himself. And I was able to really sink into his character a little bit more. There’s a lot of restraint in the dedication in the epistle, the beginning, of course.

GW: He’s addressing the Earl of Essex, he’s on his best behaviour.

BC: Absolutely. And obviously, there’s a lot of care and pedantic care and passion that comes out in the core of the book. I think you get a few flecks of character here and there throughout it and in some of the marginalia. But the story of cheese at the end really seems to… you hear him. And that’s always a real joy because there’s something about reading in original pronunciation. And bearing in mind I haven’t heard the modern accent version of this book recorded by a very fine colleague, so I don’t know how his version of George Silver sounds.

GW: Well, I’ll send it to you when it’s done.

BC: I’ll look forward to it. There’s certainly a degree to which accessing these sounds, like I said earlier by Shakespeare, there’s a degree to which you feel like you’re accessing the cadence and rhythm of the speaker or the writer. And so I feel like I got a cut close to the man. I’d like to have a drink with the guy at the end. I’m not sure I’d want to spend too much time. I’d be way out of my depth. I would give that ticket to you to sit in the pub and listen to him harp on about all the different times and manners.

GW: He wrote a second book called Brief Instructions Upon My Paradoxes of Defence, which is basically explaining all the stuff he failed to explain properly in the first book. This is why I’m really hoping that the campaign picks up a bit and does really well so I have enough money to pay you to do the second book.

BC: It would be a nice complement to the two, certainly if it fills in, although having flipped through it, his sense of brief is different. Yeah, but I had a question, if I may turn the tables? I’d love to hear a little bit about from someone that I imagine anyway, that understands so much more of the true meaning of the things that he’s describing. In other words, I imagine that you and your colleagues would be able to look at Paradoxes and go, OK, he says this here, so we move this hand here. So this movement is what he’s talking about.

GW: What is his guardant fight, and what is his variable fight, for example.

BC: The things that he describes so particularly and so carefully, I imagine that you and your colleagues are able to get it up on its feet and understand a way of fighting that’s lost?

GW: Yeah, absolutely.

BC: That’s incredible.

GW: To be strictly fair, my area of expertise is not George Silver. I mean, I’ve done the Silver stuff. I started twenty five years ago and I got sort of seduced by the Italians. Silver would hate me for that. But most of the last 20 years, most of the stuff I’ve been practising has been Italian. But yeah, if you include his Brief Instructions then there is a fairly straightforward path to actually recreating that as a fencing system that you can actually apply against itself and against rapier fencers and against anything else is likely to occur in the 1500s.

BC: That’s incredible. And it’s effective?

GW: Oh, absolutely. Yeah, very straightforward.

BC: First, I thought it was he was, from your point of view right in his admonition?

GW: I cannot speak as to how Italian fencing was being taught in the 16th century in London, and we don’t have very many sources for that. The one we do have that in the most detail is Saviolo’s Practise and it’s very difficult to get a good working interpretation of Saviolo because he doesn’t describe things in a way that makes it easy to reproduce. But there are a bunch of other Italian sources of that period which go into a lot more detail about how to stand and how to strike and all the various things you should do. So reproducing a working fencing system, if we look at Italian rapier of shall we say, 1600 or thereabouts, it is not quite as Silver describes it. For instance, they use the blow a lot. He’s like, oh, there is no cutting with the rapier. Well, every rapier source that we have includes cuts. Without exception. I can’t think of an exception. But then he’s maybe describing how it’s fenced in the fencing schools. And it could be that when you were fencing your friends with rapiers, you weren’t allowed to cut because maybe you’d break a finger or whatever. And the protective equipment they had was OK for thrusts, but not OK for cuts, for instance. And then perhaps they were wearing different protective equipment, if they were wearing any at all, for doing like broadsword stuff, what Silver what call the short sword. Funnily enough, Silver’s short sword has a bloody long blade. If you follow his instructions about how to hold it, it’s about thirty six inches on me. That’s a three foot blade and sometimes maybe 40 inches. Actually I have a tape measure right here. On me, it’s 40 inches.

BC: Sort of arm length, isn’t it?

GW: My rapier has a forty two inch blade, but it probably ought to have a forty five inch blade. So we’re not talking about a really short sword. We’re talking about something that when you look at this, there are only a couple of pictures in the book and one of them is Silver showing you how long the sword should be, and when you measure that on yourself, for me, it’s about forty one inches. So, I think a lot of his dislike is that the way Italian rapier was being taught in London in that time with the thrust, it’s very difficult to fence and not get properly injured, whereas if you’re doing, for example, sword and buckler with sharp swords, as I’ve done, you can fence your friends sharp on sharp and nobody gets hurt, because you’re not committing to these explosive long lunges where if something goes wrong, there’s nothing you can do about it. If your friend accidentally sticks his face in the way of your point, then it’s over. Whereas the manner of moving and the overall style of action with the sword and buckler is a lot less committed to a single action.

BC: This is so interesting because there’s a point, and I can’t quite remember where it was in Paradoxes, where it’s like Shakespeare lifted the description and gave it to Mercutio when Mercutio was complaining about reversos and stoccatas. The problem is, of course, the Silver Paradox is in 1599, and everyone thinks that Romeo and Juliet was around 1594.

GW: It could well be that Silver borrowed it from Shakespeare.

BC: It could be. Yeah, I suppose so.

GW: If Silver was gentlemen who goes to the theatre he would hear this and that even may have inspired him to write the book.

BC: Well absolutely. Or vice versa and we’ve got the dating of Romeo and Juliet wrong, which some people think. It’s such a lovely light shedding on, most people would be like, oh, yes, this is the bit when Mercutio complains about fight styles, well, why? It’s not just the flashiness of it. It’s ironic that, hearing you talk then, that there’s an inherent danger in the style. That means that if you’re on the street as a young rake and you’re fighting with your friends and your frenemies, then there’s one style that means everyone gets to go home and there’s another style that means that you don’t necessarily get to go home. And of course, shortly afterwards, he doesn’t get to go home. So this is the sort of thing that excites me about working with and collaborating with folks that really know how things were, because it can so sharpen up and open up how we do things today.

GW: I need to go read Romeo and Juliet again. It’s been a long time since I last read it, but yes, I shall give that some thought. Now there are a couple of questions that I ask all my guests, and I know we’re running a little close to time and you have stuff to do, which is probably very interesting. So I will try not to keep you from it. So first is what is the best idea you have haven’t acted on?

BC: Wow, that’s a great question. Gosh, well, I found myself as a creative producer in the last 10, 15 years, and one of the things that I appear to be good at is acting on great ideas and making them happen, and I think the curse of creative production in that respect, being a creative producer, is that you’re beset with them all the time. So I was walking past an old dilapidated pub yesterday and thought, I know exactly how I’d be able to turn that into a success. I don’t have time, I’ve got to get back to the Shakespeare stuff. Oh, I’ve got this great idea for this, that and the other. And most of them I get to. I haven’t moved to Japan yet and I’ve always said that I would like to, but I don’t suppose that counts.

GW: It totally counts. Moving to Japan. If that’s your great idea, you’d like to do, then.

BC: No. Well, the greatest idea that I think I’ve had, I am acting on it and I think it ties into the question which I think you’re going to ask me next.

GW: If you had a huge sum of money to spend on improving historical performance worldwide, how would you spend it?

BC: So I think the two questions fused together for me. I’m building a huge project for the Shakespeare North Playhouse, which is just finishing being built in Knowsley, in Prescott, the Borough of Knowsley, the town of Prescott, just on the outskirts of the metropolitan borough of Merseyside, just ever so slightly south of the Lancashire border. They’re building a new original practise theatre space. It’s loosely based on a similar sort of design to the indoor playhouse that Shakespeare’s Globe built. And I have a building project for the first year of its life which will involve basically mimicking the rhythm of Shakespeare’s crew, putting on a different play, not every day, but every week. And we’re going to need a lot of money to make that happen. That is the best idea, I think, or one of the biggest ideas that I’ve ever had. Certainly the biggest project I’ve ever built. And, well, we’ll see whether or not I make it happen.

GW: OK, well, take a moment to sell it. What will give people what they don’t already have?

BC: There’s an idea that Shakespeare and his actors who were performing together for 20 years. I mean, just think about that for a sec. I mean, think about your best friend and how long you’ve known them and how well you know them and how you can intuit, to a degree, what they’re thinking and feeling. Now, think about you best colleague, your work colleague, the person that you’ve worked with the longest and how, having worked together, if you’re lucky enough to get to be with them every day, how again, you can intuit the way they might react to things. Now think about that in terms of play. And in terms of performing and in terms of performing in the same space with those same people, and there’s not just one, but there’s many of them, and you’re also entertaining and bringing delight and light to people’s lives and oftentimes those same people, that returning audience. And so a bit like modern audiences might get to feel that they know the actors in their soap operas that they love and they have a relationship with them. But you’re in the same space as these people, day in, day out. And you’re working so fast, you’re putting on different plays, at least every week. Shakespeare and his actors were said to have 40 plays in their heads at any one time. And what does that mean in terms of memory? If you don’t have very much rehearsal time, how quickly can you raise a play? Now, we’ve explored raising plays in a couple of weeks using original practise methods. We’ve explored raising them in five days quite a lot. And we’ve done three day raisings and we’ve done a single day raising. And the biggest question has been yes, but surely you can’t memorise the part of Hamlet in twenty four hours? And my response to that surely isn’t the Airplane joke, but it is well we just don’t know what the memory muscle is capable of, if it’s been well trained like any other muscle, if you take it to the gym and make it work, you it will strengthen and gain. And I’ve been on a personal mission in that I’ve learnt the Shakespeare parts in two weeks and in five days and in three days and on our Japan tour in 2019, I learnt that part of Claudius in Hamlet on the way to the gig in six hours on the train.

GW: Wow, that’s quick. People can memorise an entire deck of cards. You shuffle a deck of cards and you do them one at a time and they watch you do that in about a minute. And they have the whole deck memorised.

BC: Absolutely. The memory palace, all those kind of techniques. We’re working with neuroscientists for this project as well. We talk about memory markers and the things that facilitate memorisation like that, like keeping so many things the same, but just changing some things every now and again. So you’ve got this great performance space that doesn’t have much set in it. How do you change the space ever so slightly to allow memory markers so that you, in the haze of the 30th different play that month, how do you go, Oh yeah, that’s this play, not that play because there’s a particular type of hanging or whatever.

GW: Yeah, but also it’s like speaking your language, if I’m in Italy speaking Italian to my Italian friends who are kind enough not to laugh at my accent, I don’t accidentally slip into Finnish. But if I don’t practise, then all the languages kind of get blocked together in my head into a box marked foreign and being picked up from the taxi at an airport in Spain, I might start speaking to the driver in the wrong foreign language. But after a while, when everyone around me is speaking that language, I sort of switch and I don’t get them confused because they’re different.

BC: Yes. Especially the bit to the airport, because I think no matter how experienced you are when you’re travelling so much and you’re fatigued in that particular travel way, all the airports blur into one and you go into your pocket and you’re not sure which coin you should be passing out. And that’s degree of fatigue that they would also have been experienced and practised in after having done this for many, many years. Now, one of the conversations that I and my fellows have had over our explorations in the last 20 years is we can’t afford and no one would fund us to be together for 20 years, although some theatre companies have been very lucky to spend that amount of time with each other. But they certainly don’t put on six plays a week and have 40 plays in their heads. So that’s the exploration. We’ve got this new playhouse and we’re going to infuse it with Shakespeare. We’re going to build bridges with the community and we’re going to push the explorations of memory and production, compacting Shakespeare’s career from 20 years down to one. And at the end of it, we’ll have a group of actors that have all of Shakespeare’s plays in their heads and will have cut closer to a modern version of what it might have been like four hundred years ago than I think has ever been done before.

GW: That is super cool. Sold. And if you need any help with the swords you just give me a ring.

BC: One hundred percent.

GW: So where can people find you online?

BC: Well, if people want to find out more about me, they can do to bencrystal.com, and I’m also @bencrystal on Twitter.

GW: Brilliant. Well thank you very much indeed for joining me today, but it’s been a delight talking to you.

BC: Likewise, Guy, I look forward to the next one.