Guy Windsor

Chris Schweizer is a three-time Eisner Award nominated cartoonist, a writer, concept artist and illustrator who lives in rural Kentucky with his wife, daughter, two cats and a long legged dog. He also supplied me with a gigantic list of his previous jobs. So I’m going to give you the whole thing just because it’s kind of funny. He has been, among other things, a college professor, a hotel manager, a movie theatre projectionist, a guard at a mental hospital, a martial arts instructor, a set builder, a church music leader, a process server, a life drawing model, a bartender, a car wash attendant, a bag boy, a delivery boy, a choir boy, a lawn boy, a sixth grade social studies teacher, a janitor, a speakeasy proprietor, a process server, a video store clerk, a field hand, a deck hand, a puppeteer for a children’s television show, a muralist, a kickboxer and a line worker at a pancake mix factory. But now he makes comics, and he likes that job the best. That is by far the most comprehensive list of jobs I’ve ever come across. So without further, ado, Chris, welcome to the show.

Chris Schweizer

Thank you so very much, Guy. I’m really, really glad to be able to be here. Thank you.

Guy Windsor

You’re very welcome, and let’s just orient everybody. I said rural Kentucky, but whereabouts?

Chris Schweizer

Kentucky’s broken up into a few different regions. I’m in what’s called the Western Coalfields. So I am about two hours north of Nashville, Tennessee. I’m on the western half of the state, sort of the last hiccup of hills and mountains before we turn into the swampland of the Jackson Purchase and then flat farmland. But I’m about an hour from anything and two hours from anything big. So you know, if I need to get decent lumber, or if I need to get art supplies or something like that, I’m two hours in the truck.

Guy Windsor

Wow. Okay, so are pretty efficient, therefore, about deciding what you need and making a proper shopping list before you go.

Chris Schweizer

One would think, I try to be. My wife is much more efficiency minded than I and so she’s tried to drill it into me. Usually, yes, if I have to go to town to get this or that, you know, we do have smaller stores in our area that we can get things. It’s just a lot of the stuff that I use for work, I can’t get here, so I have to go elsewhere. And that’s usually a twice a month thing. It’s not frequently.

Guy Windsor

Fair enough. So properly rural, and therefore loads of peace and quiet for drawing.

Chris Schweizer

Yeah. Well, actually, we do live in the middle of our town, so we have a small town, but we are about a block from the primary intersection where the two large streets meet. So that said, it is still nice and quiet here, and I usually take walks in the morning out in the country or drives out in the country. And so I get on the road for about three minutes, and I can be out on an old mine road or logging road or something like that, and have complete isolation, which is nice and we just got that long legged dog about two weeks ago. He’s at the vet right now. We might be having some health issues, so that’s changed my walking pattern a little bit because I’m doing it more frequently throughout the day. So the hour that I usually take in the morning, I’m starting to trim that down a little bit and parcel it out.

Guy Windsor

What made you move to rural Kentucky?

Chris Schweizer

Well, I grew up from the time I was 11, about 30 minutes south of here, in a different one of those regions. So those regions that they’re broken up into, we have very little to do with each other. So even though it’s the next nearest town, there was never any back and forth between the two. Just for a variety of reasons, geographical ones, social ones, economic ones, there just was very little overlap. So I grew up down there, and I met my wife in college. We went to Murray State University, which is even further Western Kentucky in the swamps, and this is her hometown, so her family has been here since before the county was founded. So about 1802, 1801, something like that. So my daughter is ninth generation for this county, which for the UK is not particularly spectacular, that’s old hat, but here, it’s rare.

Guy Windsor

Well, I mean, I was first generation in the county I was born in. I’m not 100% sure. It’s not the sort of thing I really keep track of.

Chris Schweizer

We moved around a bit after we got married. So we got married relatively young. We finished college, and then we were in Mississippi for a little bit. Then we went to Atlanta, where I went to grad school and then taught, and then we were in Nashville for a bit, and then we ended up here, and have been here probably eight or nine years at this point, so it’s longer than I think. It feels like a short stretch, but my daughter has been here since she was five, and she is about to turn 15.

Guy Windsor

I have a 15 year old.

Chris Schweizer

Oh, congratulations. We’re probably dealing with similar things at the moment.

Guy Windsor

So far, my two girls are 17 and 15, and so far, the whole teenage monster thing hasn’t really happened. They still talk to us, they still hang out with us. They’re still lovely. And we’ve seemed so far to dodge the bullet, but I keep expecting a bullet to come.

Chris Schweizer

Yeah, thus far. Likewise, things have been mostly good. You know, there’s some adolescent angst and trouble, but yeah, her relationship with us has been consistently good, which we’re very grateful for.

Guy Windsor

I think if you can just keep them talking to you, then you can usually stave off the worst of that sort of thing. Because I think teenagers do really badly when they’re stuck in an echo chamber of other teenagers, or an echo chamber of the internet. But if they have parents they can actually talk to, or just adult role models they can actually talk to, yeah, that makes everything a lot easier, I think.

Chris Schweizer

Fingers crossed that that maintains as it’s been going.

Guy Windsor

Bless the little treasures. Okay, now I do actually have some non-children related stuff we should talk about. So how did you get into drawing comics?

Chris Schweizer

Well, a lot of it, like most cartoonists, I drew a lot as a kid. So that’s sort of the general answer, is that you never stopped drawing. For me, a lot of it was I grew up with it. There was a lot of respect in the household for comic strips. My dad had lots of book collections of, you know, we got Calvin and Hobbes as soon as it came out. That started up when I was about five, and so I started reading that immediately. We had a lot of Peanuts books. We had Pogo books. My grandfather had been a big Pogo fan. Walt Kelly, who did these funny animal / political satire strips. And at one point, he lived in Central Florida and was an architect, and a lot of cartoonists had moved to central Florida for some reason in the probably 60s, I guess. And although I don’t know that Walt Kelly was among them, he had a mutual friend, and my grandfather had been gushing about him. And the friend told Walt Kelly, and Walt Kelly sent my grandfather an original strip. So we had that hanging in the house. And my dad would point it out to me when I was a kid. He would, he would say that it was drawn with, he used a blue pencil, which is like a light blue sketching pencil to do, to lay in the roughs, and then would ink on top of that with this beautiful, very slick brushwork. And my dad would point out to me, and he’d be like, “Look, you see that that blue pencil? That’s because that wouldn’t pick up on copiers. And so he would do the sketch first, and then he would ink on top of that.” Some kids, I’ve heard it never really occurred to them that it was a job until it was, it’s just the thing that existed. I always knew that somebody was making these and from a very early age, I said, that’s what I wanted to do, without really having a sense as to what that entailed. But you had to pick a job when you were a kid, what do you want to be when you grow up? I want to be a cartoonist.

Guy Windsor

The jobs I wanted to do when I was a kid was either be a ninja or be Conan the Barbarian.

Chris Schweizer

Well you found the perfect combination.

Guy Windsor

So what did you go to college for if you wanted to be a cartoonist?

Chris Schweizer

When I was an undergrad, I went for art originally, and very quickly lost interest in it. I did not particularly like the subjective aspect of art, but I also was not disciplined enough to really work at the objective aspect of it. And so I did a few classes, sort of the basic design classes, and wanted to switch. So I switched to literature. No, first I switched to theatre, and I did theatre classes, and then I switched to English, and then I went to your neck of the woods, to the UK. My now wife, at the time we had been dating, and she was in the Honors Program, and she had decided to do a study abroad program in Segovia in Spain. And I thought, well, that sounds great. I want to do a study abroad program. And I looked at it, and I saw the price tag, and I thought, oh, well, no, I do not want to do a study abroad program, but I liked the idea of it. And so my dad was a choral composer, and one of his frequent compositional partners and good friends lived in York and had some spare rooms, and said that I could live with him. And so I set up some directed studies classes over the internet. They were definitely the first internet classes that this particular professor had done. It might have been for that department or school. I’m not really sure, they didn’t do online classes at the time. This is 2000 into 2001, beginning in 2002.

Guy Windsor

The internet wasn’t really properly a thing in most people’s houses yet.

Chris Schweizer

But we arranged for me to do medieval literature and something else. And now, having since taught, I know how much extra work this was for this professor, and I can’t believe that he was willing to do it. So I’m very, very grateful to him. But I would go twice a week and pay two pounds for a half hour at an internet cafe and type up everything I could as fast as I could. I didn’t have a laptop. I’d do all my notes I had to time and send it off on whatever my assignment was that week. And so I was based out of York but I travelled around all over there, and while I was there, I found some cartoonists that I really liked. I found some work that wasn’t available where I lived, it was available in the States, but it wasn’t available in rural Kentucky. And so one of those was a Canadian cartoonist named Seth, just the single name, and I really liked his drawings of buildings. And I was like, well, I want to do that. And so I went to the Jorvik Viking Museum, and I spent almost no money while I was there. I think I lived there for about five or six months, and I did the whole thing after having paid my Brit rail and Euro pass. I think I did the whole thing for about $900 because I was living just on cheese and clementines, basically, but I did buy a little feathered calligraphy set. It had a feathered quill, the ones with a leaf bowl tip, like a little metal tip and an ink thing. And I thought, well, I’ll write a letter in this, and it’ll be very funny. And I went to draw a little sketch at the end, and it was the first time I’d ever used a pen that allowed for a variable line the way that you see in a lot of comic art. And I was elated. And I started drawing, and I started drawing. And the next week, I must have drawn 1000 things. I was wandering around York and just drawing everything I could see. And for the first time ever, I could create the sort of line that I had seen in art but had never been able to do. And by the end of that week, I decided I wanted to change back to an art major, and so I contacted my school, and I said I wanted to change back. And the umbrella for that was graphic design. So I did graphic design, but I did as much of it by hand as possible. So the text I did by hand and that sort of thing.

Guy Windsor

I imagine the English Lit and theatre would be very helpful in things like the construction of stories and the writing component of creating.

Chris Schweizer

Absolutely, yeah, theatre especially, when we’re talking about comics, so often the terminology that we use is screen terminology, and that does make sense, because we are looking at things through a frame. And so when we’re talking about the 180 rule, or moving from one side of the screen to the other, something along those lines, foreground, we tend to use a lot of screen terminology, but there are aspects of theatrical design that I think are also very, very helpful, especially staging and the placing of characters in relation to each other. And yes, that can be a screen thing as well, but I tend to think of it more from the standpoint of how things work on stage. And I think tend to think of sets and environments that I’m drawing as sets and environments that can be built and adjusted versus found. So very rarely do I look at a real place and think I’m going to use that as the type of setting for my story. Most of the time I will construct it, either in my head or in sketches and designs, or sometimes if it’s something that’s going to be featured throughout, like I did an action book recently called Six Sidekicks of Trigger Keaton. And there was an entire issue that was one long fight scene that took place in this Egyptian temple set at a movie studio. And so I made a digital model of that set and used that so that I could look at it while I was working, just for convenience and ease as I went along.

Guy Windsor

When you’re drawing these days, are you drawing on the computer, or are you drawing by hand on paper?

Chris Schweizer

It’s a mix. I do my preliminary work on the computer. So when I’m sketching and doing that pencil draft, like I mentioned with the Walt Kelly, that blue pencil, I will do that digitally, because I tend to make a lot of mistakes, and that has become okay. And I make different mistakes than I made when I was younger and first starting out. So, I still make the same number of mistakes, but they tend to be more precision mistakes.

Guy Windsor

That’s true in every discipline. You make the same number of mistakes if you keep practicing, but yeah, just differently. And less obvious to the layman.

Chris Schweizer

Yes, exactly. And sometimes I will force myself to say, I’m going to look at this tomorrow, and I will not notice the things that are wrong. And that’s usually the case, but I like working digitally, because I can keep tweaking those things. And the big shift over the years hasn’t been that I make fewer mistakes, it’s that I now have the confidence that eventually I will get that drawing right. I no longer get frustrated if something is taking six times, because I know that when I hit the seventh or eighth time, I’ll get it. So I do that stuff digitally. And then usually what I’ll do is I will print it out in light blue or potentially in black. If I’m going to light box it, if I’m going to watercolour it, I usually light box it in ink.

Guy Windsor

You’ll need to explain that.

Chris Schweizer

I’m sorry. So a light box is basically a flat white table, or now they come in tablets, and they’re very cheap. They used to be pricey, and they have fluorescent bulbs in them, and they create a glow. You can put one piece of paper on top that is the thing that you want to trace or use as your base image, and then you place the piece of paper on top of that, on which you want to draw, and so I can do a rough drawing and get the proportions the way that I want, and print it out, and then put that on the light box and put my drawing sheet on top of that, and do my final drawing that way, without having to erase pencils or leave them there. If I’m not going to be watercolouring, if I’m just inking, and I’m going to scan in black and white line art into the computer. Then I will print that line art out in very light blue. And I could, in theory, use any colour like the scanners. I’ll take them all out now the blue, but force of habit and tradition lean you to do blue, just because that’s the historic standard. And then I will ink, traditionally, so I have a drawing desk, and I will go in with a usually a pen or a brush pen, as opposed to actually dipping a brush or a pen, just because I feel like I have a bit more control, and it’s a little bit faster, and I value speed a lot when it comes to the execution of work.

Guy Windsor

Okay, so you also teach drawing.

Chris Schweizer

I did.

Guy Windsor

Yeah, you have taught it. You very kindly sent me a whole bunch of stuff, so I didn’t have to go digging around on the internet doing my research.

Chris Schweizer

I still do occasionally. I’ll get brought in to be a visiting professor here and there, but not as a full time profession anymore.

Guy Windsor

Yeah. Okay. I teach historical martial arts, so I have an interest in in teaching. And it strikes me drawing is one of those things where all little kids draw, and then some kids, as they get older, they basically stop. And so it’s sort of a natural thing for kids to do and a common thing for kids to do. And it’s one of those things where I can totally see that, I mean, my eldest daughter, for example, is one of those people who never really stopped drawing, and so her drawing is fantastic now. And she’s never really trained it. She just got good at it by just never stopping. So how do you teach something that seems to be 99.99% just practice?

Chris Schweizer

A lot of it is just practice. The thing is, there are, and this is something that I didn’t know until I got to grad school, and I had some absolutely wonderful teachers. One in particular, Sean Crystal, who’s a comic artist who lives in Atlanta, was wonderful because it was the first time that everything I was taught was quantifiable in art. Up until that point, everything had been extremely subjective. By quantifiable, I mean, using sort of specific rules that you can absolutely break for a purpose. But compositional rules, the rule of thirds, if you divide your piece into two, three vertical strips and three horizontal strips, and it’s a larger piece, sort of a large panel with a lot going on, the viewer’s eye is going to focus in on one of those points where those vertical and horizontal axes intersect. And so you want to place your images there. Or how black and white composition works, or how tangents work, there are a lot of these extremely specific right and wrong ways to do it. And I think that one of the difficulties with art, at least art in, you know, the postmodern era forward, is that these rules are largely seen as hindrances, and therefore not taught. They’re an obstacle to creative expression. And art is so often taught as creative expression as opposed to craftsmanship, and I think that by focusing on it solely as craftsmanship, you can give students the tools by which to allow creative expression. But I’m very much of the mind that you learn the rules so that you can break the rules, and that when you break them, you are breaking them because it benefits you to do so. But the awareness of them is also an awareness of what audience expectation is and things along those lines. And so a lot of it is that sort of thing, but practice is a big part of it, because those rules and those principles, and I’m sure the same applies to swordsmanship, they really only make sense once you are applying them practically, and as you apply them practically, then when you go back and look at those principles again, things that didn’t click start to click, and they may not click for a long time. It may take weeks and weeks of doing the same thing before the principle makes sense. And I think the same is true with art. So it is a mix of practice and also looking at it through the lens of rules. But also in terms of drawing in general, for me, a lot of it is less teaching drawing that’s akin to saying that you teach fighting. You do teach fighting, but it is a very specific subset of fighting that has certain expectations and certain parameters that you all put around it, and that allows for sort of a hyper specialization in what it is that you’re looking at. And so the lessons that you teach are going to be mostly applicable to that. And can you apply them to other martial mediums? Probably, but they’re going to work best in this particular arena. And when I’m teaching drawing, it’s narrative drawing. I’m teaching drawing very specifically to the point of telling stories. So even if we’re not talking about the mechanics of how comics work, how an eye reads through the page, where balloon placement goes, all that sort of thing. It’s still all about conveying information. And so if you’re drawing a character, if you’re drawing a design, that design is conveying information, at least in terms of what I’m worried about, more so than aesthetics, it’s what does the shape of this character’s shoulder say? What do the colours of this character’s shoe say when you relate them to the colour of their hands and the colour of their head. If you teach those principles, then it doesn’t matter how someone draws. My aesthetic was wildly different from that of my grad professor, and most of my students’ aesthetics were wildly different from mine. There’s very little visual association between us, but the principles of storytelling and the principles of composition are ones that we universally share, and those are the ones that I kind of focus on. And so a person’s style, you can learn to draw in a different style. And animators do it all the time. Illustrators do it all the time. I’ve never been particularly adept at that. Like I tend to draw how I draw, because it’s the best that I can do, and drawing in that style is the best that I can hope to accomplish. And so trying to do it in another style, for me, means minimizing the quality just because this is the best version that I can do. And so everybody’s style is just going to develop as a result of practice, as a result of the influence and inspiration that they take in at particular points and junctures of their development, what their artistic priorities are, what their time priorities are. And so those are things that I think a teacher has very little control over, but I think if you give them that foundational work, they can build on top of that pretty easily.

Guy Windsor

Interesting. Obviously, I am British, and if I say to you, your mother was a hamster and your father stank of elderberries, you know what I’m referring to, right?

Chris Schweizer

I do. I do know what you’re referring to.

Guy Windsor

I should hope so. So my question is, how on earth did you get the gig to draw the Monty Python and the Holy Grail board game?

Chris Schweizer

That was a very exciting opportunity. So I’ve done a couple of board games prior to that. I did an Agincourt battle game. There was a web cartoon in the early 2000s. I mean, it continues on, but that’s when it when it launched, called Homestar Runner that had a very popular cartoon card called Trogdor the Burninator, which was a dragon. I did the art for the game for that. And so I had a couple of game credits under my belt, but I think it came largely because the publisher for the game was under the same umbrella company as a comics publisher that I had done work with doing a Mars Attack series. And I think that the game people asked the comic people who would be good for this. And the editor recommended me. And so they were like, can you send a couple of things that might work for this? And so I had a couple of Monty Python Holy Grail drawings that I had done. And so I sent those off, and the Python guys approved it. And I got put on the job.

Guy Windsor

So Michael Palin knows your name.

Chris Schweizer

Well, they probably have a lot of stuff going across their desks, but he did see the work, which was exciting. And so I’m like, ah, should I made these drawings more flattering? Who knows. But the game itself was built around a map, and so it was all these different locations from the film. And so you moved from one to another, sort of like Candyland but they also had about, I think, four or five locations that were mentioned in the film but not seen. So I got to basically reverse engineer what a Gilliam set looks like.

Guy Windsor

Because Gilliam had a very, very distinctive style.

Chris Schweizer

He did and it’s interesting, what’s amazing to me on Python, I did not appreciate this fully until I was going through and doing screen captures to use as the reference for the pictures. The sets in there, versus something like Brazil or Munchausen, where they’re much more elaborate, are so minimal and are made up almost exclusively of smoke, which is really kind of interesting. You’ll have a couple of elements that suggest the thing, the side of a building, a wall, something along those lines, and just loads of dry ice or smoke machines. And it makes me think of, and I know he was a big 19th century art buff, and it makes me think of some of the early romantic pieces that did a lot of medieval work. And they would be like that. You’d have these very misty drawings where the backgrounds are just sort of suggested rather than actually done. And so that was just a real treat, getting to go through and doing all these things. And so I did all these separate pieces, and they were water coloured. And when I was done, they said, well, now, on the map, there’s all this blank space. And I was like, well, is there going to be parchment there or something? They’re like, no. Can you connect them all like a map? And that’s very difficult after the fact, but I was able to do it, and I figured out a way to get that done, but I had done all the individual locales separately. So I’ve got a stack of those, which is kind of fun, but that one was really exciting, and it was one of the first. I’ve had a couple since then. My dad was a big Monty Python fan. He passed in 2019 and that was the first job that I had where really, for me, a lot of grief is the inability to share stuff with someone that you know would like it. In the case of your parents, an accomplishment that you have, or something like that. But also, I’ll find a store or read a book or something that I wish I could share with him, and I can’t, but that was the first job that I was really sad that I wasn’t able to let him know about because he would have thought that was very neat.

Guy Windsor

I know exactly what you mean. It looks extremely cool.

Chris Schweizer

Think it hits shelves… It’s supposed to come out this month, I think, or in September, maybe.

Guy Windsor

I’ve seen artwork of the boxes. I haven’t seen the game itself, but I’ve seen, like, adverts for the boxes. Okay, so what are the Crogan Adventures?

Chris Schweizer

Okay, so the Crogan Adventures, those were my first graphic novel series. I’d been a big Sherlock Holmes fan as a kid. And you hear about Arthur Conan Doyle feeling economically locked in to continuing to do Holmes stories, even though he wanted to do historical romances.

Guy Windsor

Honestly, I’ve got to say Brigadier Gerard is way better than Sherlock Holmes.

Chris Schweizer

I love Sherlock Holmes, but I think Brigadier Gerard is wonderful. I love the White Company. There are a lot of really fun things that he’s written. And Brigadier Gerard is great because it shows off his sense of humour.

Guy Windsor

He’s just so good, yeah. The Holmes stuff is great. It’s a special thing. And it’s no surprise that it’s become this kind of juggernaut, an icon in our society, but Gerard, I think, is a better character.

Chris Schweizer

Oh, he’s wonderful. You know, there’s a handful of those sorts of things that are comic without being silly. And I think that’s sometimes a tough balance. Another one, you had mentioned Conan the Barbarian earlier. Robert E Howard had a sort of a hillbilly Gerard type character, named Breckenridge Elkins, who is just this enormous bumpkin who gets into brawls. And they’re extremely funny stories that are sort of tangentially westerns, but they’re just these lovely things, but they kind of remind me of Gerard. They’re similarly structured, I think. But Holmes, I was hopeful that whatever I did would become a hit and that I’d be locked in. And so I tried to present myself with a conceit that would allow me to never feel locked in and so the Crogan Adventures were a series of graphic novels that purported to tell the stories of all of these different family members, these ancestors from about the 1700s up through about the early 20th century, which was kind of my window of interest at the time. And each book was bookended by a dad telling his kids a story about one of their ancestors, and then that allowed me to change genres with each book. So the first one was pirates. The second was French Foreign Legion. Third was the frontier campaign of the American Revolution, and it would give me the opportunity to jump around and do a spy story, or, you know, that kind of thing. And it was well received, and I garnered a couple of award nominations, for which I’m very grateful, and I think most of the audience that I have was built off of those books. But once I stopped teaching and had to work and was doing comics as my full time job, the publisher and I were unable to come to any kind of arrangement where I could make anywhere close to a living wage working on those books, like I had proposed a pretty modest page rate against advances to do it in a publishing schedule, and the editor that I worked with was on board, but then the publisher was like, no, I don’t want to do it. And so that was essentially the end of those, because although I retained the rights to them and I could take them elsewhere, at that point, I started working on other projects, and I kind of lost steam for it. And I also kind of lost steam on more modern era historical stuff, like I used to love the 19th century and 18th century, but that was operating under an assumption that there was sort of a forward momentum of social progress and seeing things repeat over and over, you see them in 1880 or 1830 and think, well, surely this will be reconciled by now. And it’s not. Was really disheartening to me, and was very difficult to dwell on those eras. And so I still love history, but I’ve started pushing further back into more the Middle Ages and the ancient stuff.

Guy Windsor

The Middle Ages is kind of where it’s at. Okay, now, for reasons that will become obvious in a little bit, you are obviously a sword person, but you haven’t done a great deal of sword training, but on your list of jobs, you have martial arts instructor and also kickboxer. So, just because this is the Sword Guy Podcast, and we talk about swords and martial arts a lot, what is your martial arts background? What martial arts have you done? And why haven’t you done more swords?

Chris Schweizer

My martial arts background was I did karate when I was younger, and then starting about age maybe 11, I started doing Chung Sul Kwan, which is essentially taekwondo. And I did that up through college, and I became an assistant instructor at our studio, teaching some of the kids classes, and then teaching one of the weapons classes and the kickboxing thing was just, I fought for money. When I was 17 and 18, we made fake IDs so that we could enter the state fair or the county fair tough man competitions, because you could win money that way. And then also the Boxing Commission rules on the state line had changed to try and attract UFC, which was starting to come up. And so all of these bars started hosting basically these tough man competitions where you could go in and pay $50 to enter, and instead, whereas at the fairground, you would have three one minute rounds. At the bars, you would have one three minute round. And so if you were 17, you could win that just by virtue of being able to breathe quicker than somebody who was 25. So, I would do that and I did tournament stuff, but that wasn’t a job, you just did that to try and garner trophies and stuff. But once I went off to college for the first year, I would come home, because I still lived about an hour away from my school, and my girlfriend and I were still dating at the time, and she lived there, and so I would still go home and train. And I trained all that that next summer to try and get up to my next belt level, and that was with my, I don’t know what you call it, your grand teacher, my teacher’s teacher, I travelled to Tennessee and trained with him three times a week, and but once I became a sophomore in college, I stopped going home. I started having more commitments at the school, and there wasn’t a good studio within miles of me that I liked, and so I very quickly fell out of training. And once I fell out of training, I stopped winning anything that I tried, and so that that was sort of essentially the end of that. And I’ve since tried to pick it up a couple of times, and it’s just it’s never clicked. I did not treat my body as well as I ought to have when I was younger. And so, you know, my shoulders, my knees, they’re all a little bit beat up. Okay, so far as swords go, a big reason why I haven’t ever pursued HEMA or fencing or anything. I mean, I took fencing in college, and I did little things here and there, but a big part of it is the rurality. I’m quite a stretch from anywhere. And if it were a prime concern, I would make the effort. My daughter still goes to Nashville once a week for harp lessons that she started when we lived there. And so that’s about four hours in the car for her and my wife. But my work schedule doesn’t really permit that. I work a lot, and I try to have a pretty hefty output, and that requires a lot of time at the desk, and I just can’t afford taking a day off each week to pursue that, although now there is a branch in Nashville of HEMA, and a branch in Franklin, Tennessee. Neither one of those, I think, were in existence when I was there. But I’ll do a lot of second-hand instructions. So I’ve never taken anything. You know, whether it’s whether it’s Kendo, or whether it’s HEMA, or whether it’s, you know, whatever I will do sort of a session or two with a friend who does that, but not an actual instructor, just sort of to get some basic fundamentals around. And I always sparred with friends with whatever they had on hand. You know, if that’s flat swords, if it’s fencing foils, if it’s bokkens, whatever.

Guy Windsor

Did you just say flat swords?

Chris Schweizer

Well, not flat, dull swords.

Guy Windsor

Oh, right. Blunt swords.

Chris Schweizer

I don’t know. I don’t know the terminology, I’m afraid.

Guy Windsor

No, that’s fine. I felt I’d better clarify that, because I wasn’t quite sure what a flat sword was.

Chris Schweizer

And like a lot of things the comics is the only thing that I’m probably going to ever be able to claim any sort of expert or mastery of, if I’m lucky. But there are a lot of other things that I like having a sense of, if only to understand how difficult they are, because that helps to colour how I do storytelling. You know, if I’m doing a Western, my shootout scenes are going to be better if I’ve tried doing quick draw, or if I’ve tried target shooting, or things along those lines. My sword fighting scenes will hopefully be better if I have tried a variety of different swords and seen how they are. And I think as the degree of accuracy in narrative sword fights, mostly we’re seeing those on screen.

Guy Windsor

There isn’t any.

Chris Schweizer

That’s the thing. And there’s reasons for that, and you can make overtures to accuracy, but I think that they don’t necessarily translate well to these emotional moments that are coming across. You know, if you see two swords sort of pointed at each other and one of them gets through, that’s a lot less visually dynamic than a series of strikes and parries are going to be, but you can still make them feel real, even if they don’t feel accurate. And that’s one of the things, I enjoy the sparring aspect of it, but a lot of it is trying to get a sense for the feel and how difficult it is to block something or how difficult it is to hit something, because that’s going to affect how things are drawn and also help to highlight, for me, the staggering difference between what a lay person can do, and what an expert can do. Because I think, you watch a lot of movies or things like that, and the difference in ability between characters tends to be relatively minimal, frequently.

Guy Windsor

What really annoys me is that people who are supposed to be experts, they’re held up as experts, usually blunder around like beginners.

Chris Schweizer

Armour doesn’t stop anything.

Guy Windsor

Except when it does.

Chris Schweizer

Yeah, except when it does. I love drawing sword fights, and I love choreographing fight scenes and action scenes on a page as both a technical exercise and also as a character exercise. There are a lot of great fight choreographers out there. My favourite is absolutely Bill Hobbs, because I think that more than anybody else, he builds things around character. Every character that fights moves differently, and that isn’t necessarily to say they move accurately, but you know, if you’re looking at the Musketeers movies, D’Artagnan makes these big, sweeping flourishes. Aramis is playful with his, he’s like a conductor with a baton doing a little staccato number. Athos is doing these fierce jabs. Porthos is essentially wielding a club. I think that with any of these, he not only makes these fight scenes feel very character oriented, which I think is very important, but also, well, there are two different ways I think, to approach it. There’s what looks cool in a fight scene. I think that cool moves are fine in a fight scene, but they can only be used against goons and henchmen.

Guy Windsor

Yeah. I mean, cool moves are great in a fight scene, but actually you get to pull off the coolest moves against people who are reasonably well trained, because then their actions are more predictable, and so you have more scope, whereas, if they’re just blundering around and bludgeoning or whatever, there’s a lot of force there to work with. But you’re not going to get their hands moving in a predictable way, particularly. I mean, you can counter stuff just fine, but you tend to stick to pretty simple stuff, because you can’t expect them, for example, to respond consistently to a feint.

Chris Schweizer

I think one of the things that I also like about Hobbs is that when you’ve got a back and forth that seems of consequence every move matters, and that is rarely the case in screen fights, and so it feels like each time someone is striking, there is the chance that that could change the course of the narrative.

Guy Windsor

Let me just highlight what exactly you just said, you didn’t say that’ll hit them or that will kill them. You said that will change the course of the narrative. Which betrays your overall goal for the fight, which is to tell a particular story, not just any old story. The narrative needs to go like this. We can’t have this person killed. We need them injured enough that they are out of action for three months, but they have to be able to come back, for instance. Or this person has to be killed stone dead, very quickly. And maybe that person has to be killed but mortally injured, but they’re not going to die immediately. They need to go because we have this scene coming in the hospital where they’re dying, and it’s all very dramatic, right? So you’re thinking about the sword fight, not in terms of winning and losing, but in terms of the course of the narrative. I thought that was a really interesting thing just to highlight.

Chris Schweizer

Well, yeah, and that’s sort of the approach a lot of times with these types of stories. I love a Princess, Bride fight, I love things like that. But those, to me, feel more like a musical number than a narrative fight. And that’s not a bad thing.

Guy Windsor

Wait a second, the fight at the top of the Cliffs of Insanity is from a storytelling, narrative, character developing perspective, immaculate, yes, because it establishes that basically, even though Inigo is on the wrong side, he’s fundamentally a goodie, not a baddie, and the man in black, who’s obviously Wesley, while kind of acting as a baddie is fundamentally a goodie. And they have a certain level of trust and communication from the get go, because they are both masters of a particular art. And that comes across so beautifully. And every move in that fight has been very carefully put there for a good reason.

Chris Schweizer

And the verticality of the set as well, like the being able to move up and down. That fight scene is its own story in miniature. It’s not just this chapter or just this aside, and that’s part of why I equated that to a musical number, which I don’t mean in a pejorative way. It’s a song. It is a thing that tells us who the characters are and what they want, and it tells us an insight into them. And it’s an aside, but its outcome is relatively unimportant, it’s there to give us, like you said, this introduction to the characters and how they relate to each other and how they relate to the story. But they’re dancing. Versus at the end, when he’s fighting Count Rugen, and that is one of those where each move feels like it matters. He hits to the side and it pierces this arm. He hits the other side, pierces the other arm, everything that happens there is not a dance like that. It is a series of narrative beats that builds to a crescendo. And I think that both of those absolutely have their place in a story, and often in the same story. I think Kill Bill’s a great example of where the final fight scene for them is not a spectacular fight scene, because it shouldn’t be. It should be intimate. It should be close, just like the Count Rugen, like it stops being a set piece, like the crazy 88s.

Guy Windsor

The set piece, the Crazy 88s, the set piece the fight between Oren and the bride at the end of the first movie, brilliant. But the fight between Bill and the bride at the end of the second movie: just perfect.

Chris Schweizer

It is. Most action movie things I think that are really good, tend to do something similar. Die Hard has these big set pieces where he’s fighting all these guys, but at the end, it’s just him and his wife and the bad guy, like, right next to each other, like one thing happened, you know? And I think that there are ways that action sequences and fight sequences are structured in a story that can be really wonderful and lovely and I think that that because of the contrast between them, because of the contrast of the fight scene between Inigo and Wesley, and the fight scene between Inigo and Count Rugen, the latter, has so much more narrative punch, because the earlier one was so playful. And that tends to be the case in a lot of these types of things. So I love getting to play with that. And I’m working on a book right now where it’s almost all sword fights, and it’s very exciting,

Guy Windsor

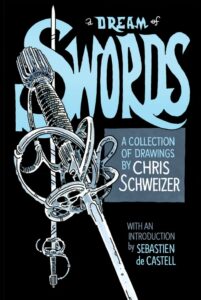

Excellent. Now, speaking of swords and books, what is A Dream of Swords?

Chris Schweizer

A Dream of Swords is the book that I’ve got coming out, which is on Kickstarter from September 10 of this year through October 10, and it is a collection of sword drawings that I’ve done from museums that I’ve travelled to over the last year or so. So I’ve been to the Musee de Armee in Paris, the Leeds Armouries, the British Museum, and the Armory collection at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. And so a lot of times I’ll do drawings in museums that are just for me, where they tend to be pretty ugly, and I’m just figuring out the mechanics of something. A lot of times it’s something that’s tough to parse looking at a photograph, because you can’t necessarily gauge its thickness, or you can’t necessarily gauge how something is connected to something else. And so I’ll fill up my sketchbooks with these things. But also I like to do pieces that I share with others. And so sometimes I’ll do something a little prettier, where I try to do a nice finished drawing. And I do think sometimes that it’s easier to look at a drawing and know what you’re looking at than it is to look at a photograph and know what you’re looking at, because I might omit certain details and emphasize other ones in order to give a sense as to how a hilt sweeps or something along those lines. And so I wanted to try, usually, when I’m colouring something, I use watercolours. And I thought, well, you know that it takes so much time to do these, I wonder if I just used indigo and did just a one colour wash for value, value in the sense, meaning the difference between lights and darks. And how many I could get done. And so I did some at the Leeds Armoury, and I got done a lot. And I thought, well, this is fun. I’ve got, you know, probably 25 of these. And then I had the chance to visit another museum. And very quickly, I thought, well, I’ll just keep doing things in this format. And because they’re monotone, I can print them relatively inexpensively versus colour printing, which is considerably more and I’ll put them in a book. And I thought I’d get about 60 done, and I ended up getting more than 100 done. And I thought, well, I’ll just pick my 100 favourites and put them together in a book. I tend to do very painfully literal titles for my art books. So this one was probably going to be titled, you know, Museum Sword Drawings, 2003 to 2004 or something along those lines.

Guy Windsor

So you did these drawings 20 years ago?

Chris Schweizer

Oh, did I say 2003? I meant 2023. I did it this year. I’m sorry. I’m just apparently very bad with dates and so, so I reached out to Sebastian de Castell, who you’ve had on the show before. Actually, his interview is how I first found your show, because I was looking to see if he had done interviews, and so I found that, and I really enjoyed it, and I looked for some other ones. And now I’m blanking on the gentleman’s name, but he’s a harpist, Andrew Lawrence King, yes, and he and my daughter’s harp teacher are friends.

Guy Windsor

The harp world is very small, yes.

Chris Schweizer

I found that interview absolutely fascinating. I’ve actually sent that one on to about probably 10 other people, including my mom, who I thought would really enjoy it in the classical music world. I just thought that was a really fascinating discussion there, but anyway, I reached out to Sebastian, who I had not met, but I loved his Greatcoats books. I really, really enjoyed them a lot.

Guy Windsor

So talking about writing fights, they are some of the best fights I have ever read.

Chris Schweizer

They are, and reading his, I have changed how I approach doing comics fight scenes in the new book, because I’ve always been very much a treat it like a sort of a movie, like I don’t have thought balloons or captions or things like that. But the thing that makes Sebastian’s books ring so much, or at least the fight scenes in the books, is that he contextualizes everything that happens in a way that makes the story play out in a certain way. So, you know, he’ll have the start of the fight, and then the first person narrator will give an aside and will start to tell something that will contextualize the magnificent ending of this fight in a way that’s very narratively satisfying.

Guy Windsor

I don’t know how the hell he does it, because it shouldn’t work. It should just interfere with the fight scene. But it doesn’t. It works every time.

Chris Schweizer

It compounds it, and it gives it a weight, and then it makes it to where nothing feels like a deus machina, when it gets to the end, because he sets it up immediately preceding it. And so I’ve been thinking about that with regards to mine, because it’s a kid, and he’s learning how to fight and so I am now incorporating thoughts in a way that I haven’t before. Like up until this point, it’s been strictly dialogue, and now I’m leaning hard into that in order to slow down the moment and allow for him to say. But if I do this, then this will happen and create a context for the for the readers. But I reached out to Sebastian because, having heard some of his interviews, I know that he is a very analytical writer, and he has considered things a lot, and I hadn’t heard him write about swords specifically, and I thought, well, I really love books that I have that have an introductory essay by somebody who is a writer that I like, because oftentimes those essays really sing. And so I have books with, you know, introductory essays by George McDonald Fraser, by this or by that. And I really enjoy them. And so I wanted to present, I wanted to create an opportunity where I would have a Sebastian de Castell thing about swords that I could read, which also would go in the book. And so I reached out to him, and he agreed to do it, and so he’s so we talked about what it might be about, and he mentioned as his title the Dream of Swords. And I said, can I steal that for the for the book itself? And he said, yeah, sure. So basically, it’s a collection of 100 swords, the majority of them European. I do have some Asian swords in there. I’ve got a couple African ceremonial swords, but the difficulty, and I haven’t yet found this. I need to talk to a curator friend about this. Almost every katana that I’ve seen has been sheathed on display, like they’re in their scabbard on display, as opposed to having the blade out.

Guy Windsor

They shouldn’t be. They should be displayed with the blade completely naked on top, and then the scabbard, the Suba and the handle mounted together underneath as one, that’s how they should be displayed.

Chris Schweizer

You would think. That is how they should be. But at Leeds, at the Met, at almost everywhere, you would occasionally have an empty blade, absent a hilt and a Suba but anything that had fittings would be in scabbard, and so that made it a little bit difficult to draw. And actually, I’ve gone through and I’ve sort of reversed engineered and just faked what the blade would look like, because I don’t have anything else scabbarded. And so I have, I’ve fewer of those than I would like, but it’s mostly some ancient stuff, a lot of early Renaissance, late medieval, some dark ages. Basically from everywhere I could find, Asia Minor, and I present them both in a close up of the hilt to try and explain, show what it is, and then a longer contextualizing view of the sword.

Guy Windsor

Just to put it in less, should we say precise technical terms, each picture includes the whole sword and a close up of the hilt. Because I’ve seen your Kickstarter page, and I’ve seen these pictures, and they’re bloody lovely, and I want one.

Chris Schweizer

Oh thank you so very much. It’s been a lot of fun. It was also really interesting, learning some different swords, like, I didn’t know that you had rapiers with hunting tips, those little lethal tips at the end for hunting boars. I don’t think of a rapier as a boar hunting weapon, but apparently you’ve got them and just all of these different things that have been really fun. And also, I may go through and do some editing. I’m trying to give them their regional names when possible, because half the time it just says “Sword”.

Guy Windsor

Museum information plaques are completely useless, most of the time. They are fine with paintings. Usually they know all about paintings. But when it comes to weapons, it’s small sword, 1760 to 1770 or something. I mean, that’s about the most information you get. It’s ridiculous.

Chris Schweizer

And so I’ve gone through, and when I can, I’ve sort of added some clarity to there, but some of it, you know, at Leeds I was able to walk around with one of the curators of edge weapons, who’s a lovely fellow, Jason, and that was a great experience. And got to see the manuscript room, which was really nice. Have you been to that one? I’m sure you have.

Guy Windsor

I’ve not been to the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds since about 1998, when it opened, shortly after it opened. I’ve not actually been in the manuscript room there. I’ve seen some of their manuscripts elsewhere, but I’ve not been in the manuscript room. No, I need to go there and make a proper visit. Thing is, I know people who work there. I’ve had some of them on the show, and I know people who live in Leeds, and I could go and we could go together and go around the armoury, and it’d be lovely. I just need to sort of make time for it.

Chris Schweizer

Yeah, that’s always difficult. I’m trying to get better about doing that kind of thing and the past, like, maybe two years, I guess two or three years, realising that my daughter’s in high school now and is steadily nearing college age. If we want to do family trips, we need to start doing them. And so we’ve been more proactive about that. And whenever we take a family trip, I usually have a day carved out to go to this or that museum, or this or that library.

Guy Windsor

Do your wife and daughter enjoy these libraries and museums?

Chris Schweizer

They usually go and do something else. So they’ll go do a variety of things, but my wife found a really cheap ticket to Paris, a round trip ticket and in February, I went, and I was like, do you want to go? And she said, how about this? Why don’t you go this time and get all of the things that we will not want to see out of your system so you can spend three days at the armoury museum. You can spend the day at the medieval museum down on St. Michel and then when we go, we can go to the Louvre. And I’m like, okay.

Guy Windsor

Top tip for an art gallery in Paris, if you like impressionists, the Orangery is amazing. It’s probably my favourite art gallery in Paris, the Orangery.

Chris Schweizer

I’ll keep that in mind.

Guy Windsor

It’s just Impressionist paintings. And last time I went there was a long time ago, and I like impressionists and it’s a fabulous, fabulous gallery.

Chris Schweizer

Well, I had a great time. I went to the Naval museum. I got a couple of swords there. I also had the chance to meet up with some of my very favourite younger cartoonists right now, who’s a group out of Paris who all have an enthusiasm for Dumas, and they do a lot of musketeers drawings, which is how I stumbled across them. And so I was able to meet up with them at a bar, and we just chatted comics and differences in the industry between the Franco Belgian publishing wing and the American publishing wing. And just and talk Dumas, which was a lot of fun, so I came back from that one with, again, a lot of these drawings, so most of them, the Leeds, when I did a lot of them at the place, and what I started doing in Paris was I would do my preliminary sketch, looking at it so that I could figure out how the hilt works, again, because sometimes those details are really hard to parse from photographs. And so I’d do my rough, and then I’d snap reference pictures for the texture. And then I would finish the drawing at home, and that gave me the chance to do considerably more than I would have been able to do on site. It was just a chance to put some stuff together. I’ve never done a themed art book like this before, and I thought it would be fun.

Guy Windsor

Excellent. Now, this should be going out on September the 13th, okay, and we’re recording this on the 27th of August. So, when this goes out, the campaign will be live, and I will probably have backed it by the time this goes out. But what I’ve done is I’ve taken the link to the campaign and made a redirectable link out of it, because Kickstarter links are ridiculously long and difficult. You can just go to Kickstarter and type in Dream of Swords, and you’ll probably find it. Or you can go to guywindsor.net/dream, and that will take you to the Kickstarter campaign. Because, of course, everybody listening is about to just go dashing off to the campaign to back it, right?

Chris Schweizer

Yes, that is the point.

Guy Windsor

I had a feeling you were not going to actually plug your campaign properly. So I thought, I better just do it for you.

Chris Schweizer

Thank you very much. I have a weird relationship with plugging. I tend to want people to find it on their own, versus, yeah, I’ll mention that it exists, and hope that you want to.

Guy Windsor

And wouldn’t it be great if that actually worked? And of course, there will be links in the show notes so people can get to the campaign from there. And it’s ending on October the 10th, so you need to scurry along and back it quickly,

Chris Schweizer

I’ve saved most of the original art for these, so I have the different pieces. So that’s going to be a tier, as well.

Guy Windsor

So people can buy original, hand drawn Chris Schweizer, original drawings of swords. Excellent.

Chris Schweizer

And based on your recommendation, I’m also putting up two sets of prints as well. If you don’t necessarily want a book, or if you’re overseas and because shipping from the US is killer, and I apologise for that, but whereas a book costs quite a bit to send, prints don’t, and so I’m going to have a set of three rapier prints and a set of three longsword prints so that folks who have an enthusiasm for either particular branch, will be able to get something like that.

Guy Windsor

And will you be producing an eBook?

Chris Schweizer

Yes, yeah. There will also be a digital version, and that’ll have Sebastian’s essay in it, and I’ll have a little afterwards, I think, with some sword terminology, explaining stuff and knowing which swords came from which museums if you want to see them in person.

Guy Windsor

So, people who are outside the US, probably the easiest thing to do is get the PDF and the packet of prints, or two packets of prints, if you want them both. Excellent. Okay. Now, you obviously do quite a lot of stuff, but I have to ask, what is the best idea you haven’t acted on yet?

Chris Schweizer

I about half acted on it. I had an idea for a story set in mid-19th century Manhattan, sort of the Gangs of New York era, the asparian tribal stuff and this is based on real characters, this kid gang whose illegal activities were to finance the fan fiction plays that they would put on in the warehouse basement of a tavern for other kids.

Guy Windsor

Is that real?

Chris Schweizer

That’s real. They’re called the Baxter Street Dudes, and so basically, whatever was really popular at the time, like the Mose, the big Mose stories, or things like that, they would stage their own smaller, very special effects heavy version. So they’d steal gunpowder to make explosions, they would have fake blood spraying out in the audience. It’s basically the equivalent of 14 year olds today making their own horror movies in their backyard. And so they would do this, and in doing this, they ran afoul of other gangs whose territories they were encroaching on. So they’d have to set up a guard outside to fight off the other gangs who would be trying to assault the customers that were coming in to see the show and all of this stuff. And so I was able to find basically every piece that I was looking for to fit this narrative puzzle in a way that was very satisfying. And I was really excited to do this book, and I took it to my literary agent, and I said, there’s really only one publisher that I think this would be a good fit with, so I’d like you to pitch it exclusively to them. And he said, that’s a terrible idea. Let me shop it around. I said, no, no, it should just be them. And so we took it to them, and they looked at it for a very long time and eventually declined. Because it was such a stretch, they were like, who wants to buy a book about kids in the 1850s putting on a play?

Guy Windsor

Who wants to buy a book about kids who get sent off to wizarding school?

Chris Schweizer

You know, I agree. I think it’s a surefire idea, but I think, you know, it kind of carries things across. But at that point, I kind of lost momentum at it. I was in the midst of another project, and it just kind of fell by the wayside, and so I never took it anywhere else, but I’ve still got that, and I’d love to see something happen with it someday.

Guy Windsor

Do it.

Chris Schweizer

Well, I’m currently working on that swashbuckler, but once that one’s done, I’ll keep it on the horizon.

Guy Windsor

The Baxter street Dudes. Yeah, that sounds absolutely awesome.

Chris Schweizer

The villain is the guy who invented Wyatt Earp’s enormously long barrelled gun. I’m suddenly blanking on his name. But he was a political enforcer in that area who was charged with making sure that the gangs didn’t overstep, and also paid their bribes to the city officials. Ned Buntline, that’s his name. The Buntline Special is what that type of gun is called. And so I thought, well, he’s just an awful human being. I read a biography about him called The Great Rascal. It was wonderful. Just a real scumbag. And I thought, well, he’ll be a fun guy to bring in as the as sort of the heavy who’s like, y’all need to tone down your operations, or we’re going to shut you all down. And then I found out that he wrote most of the popular Mose plays that were done in the Bowery in that period, and I thought that’s absolutely perfect. They’re going to be doing a fan fiction version of one of his plays. And when he comes to shut him down for the thing, he sees their poster, and he’s like, what’s this? And they’re like, that’s our play. And he’s like, no, it’s not. And again, this is a historical figure that just everything came together so well. So I’m hoping I can do something with that.

Guy Windsor

Yeah, maybe let your agent shop it elsewhere.

Chris Schweizer

I will. My poor agent. I have never followed his advice, always, to my detriment, he’s like, you should take it to this, this will be the good publisher. And I was like, I like this editor at this other publisher. We worked well together, and I’ll go there, and then that editor gets let go, two weeks after the contract gets signed. And, yeah, so I’m listening to him now.

Guy Windsor

I was going to say, I have a piece of advice for you which is, maybe listen to your agent. So the best idea you haven’t acted on yet is, actually, listen to your agent.

Chris Schweizer

Actually, that is a yes, that is it. I’m doing that.

Guy Windsor

Excellent. So my last question, somebody gives you a million dollars. I mean, normally it’s to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide. But you’re not in historical martial arts.

Chris Schweizer

I can still use it to expand historical martial arts worldwide.

Guy Windsor

Fine. You can use the money however you want. How would you spend it?

Chris Schweizer

If I were doing that, I feel like one of the biggest helps, the thing that has the biggest ripple is exposure to youngsters, I think. And so I would put together some sort of school visit project where people come in to elementary or middle school. So basically the age six through age 14 to go in and do a demonstration of the sword fights, kids would go nuts for it. You do it in the gym at an assembly. And then talk about how this is a result of research and history, and how archaeology and how libraries play into this and all this stuff and showcase how athleticism and some of the humanities are intertwined, or can be intertwined, in a way that I think would make kids more excited about both and also more likely to pursue that sort of thing as they get older, or, if not that sort of thing, to open their eyes to the opportunities of similar corollaries.

Guy Windsor

Yeah, I’d have been a lot more interested in history at school if I’d known what I was going to do for a living. Because a lot of the stuff I got taught in history at school wasn’t particularly interesting.

Chris Schweizer

I’m in the same boat. And I loved reading historical fiction and stuff like that when I was a kid, but I did not ever enjoy my history classes. And I think it’s because, largely, the way that it works in the US is, if you are an athletic coach at a public school you are eligible to be an athletic coach if you are a teacher. And so a lot of times, what will happen is they will hire an athletic coach and put them in a teaching position. And math requires a specialty. Science requires a specialty. English requires an understanding of grammar, etc. History, you can just read from a textbook. So most of our history teachers are the baseball coach or the football coach or something like that. And that doesn’t mean that they can’t also be a good teacher, but it’s coming at it from a different perspective, and so you don’t necessarily have a history enthusiast teaching the history classes.

Guy Windsor

You think that would be like the prime directive, whoever’s teaching their subject should really like it. If it bores the teacher, why the hell would it not bore the students?

Chris Schweizer

Some teachers are switched around. I think they have probably a lot less agency over what it is specifically that they teach than they might like. It’s very rare that I had a history class that I really enjoyed, and once I got to college, I went nuts for them, and I thought they were great, like I absolutely loved my history classes.

Guy Windsor

Well, yeah, because the people teaching them at college tend to be serious enthusiasts, to the point they’re willing to take a very low paying job, just so they can go on doing the thing. So you’d spend the money basically creating an outreach program where historical martial artists go around schools, giving demonstrations and presentations and basically turning kids onto the idea that historical martial arts is a serious discipline that they can actually follow, and it’s also a very cool thing that they maybe didn’t know existed. If I had the money, Chris, I would certainly give it to you.

Chris Schweizer

Thank you very much, Guy. I appreciate that.

Guy Windsor

Excellent. Well, thank you for joining me today, Chris, it’s been lovely to meet you.

Chris Schweizer

It’s absolutely lovely to meet you as well. Guy, thank you so much for having me.