GW: I’m here today with Erin Fitzgerald, who is a historical martial arts practitioner, graphic artist, and has a really unusual day job which we will get into in the interview. So without further ado, Erin, welcome to the show.

EF: Hello, Guy. How are you? Thanks for having me.

GW: I am fine and all the better for seeing you. It’s been a very long time since we were last bashing each other over the head.

EF: Yeah, well, when was that? Was that maybe WMAW?

GW: No, it was probably when I visited Chicago in 2017.

EF: Okay.

GW: It was a long time ago.

EF: That is a long time ago.

GW: And am I right in thinking you are in Chicago at the moment?

EF: I am. Rare occurrence, one might say, but yes, I am.

GW: Why a rare occurrence? I thought you lived there.

EF: I do. I do travel a lot, though, so, you know.

GW: Oh, yeah, of course.

EF: I always consider travelling my second home, if that makes any sense.

GW: Yes, absolutely. So, yes, there’s the home you live in half the time, then there’s airports and aeroplanes for the rest.

EF: Oh, yeah. For sure.

GW: Okay. So why don’t we start with your day job? Because you have a different view of historical timeframes than most historical martial arts practitioners, I think. So what do you actually do for a living?

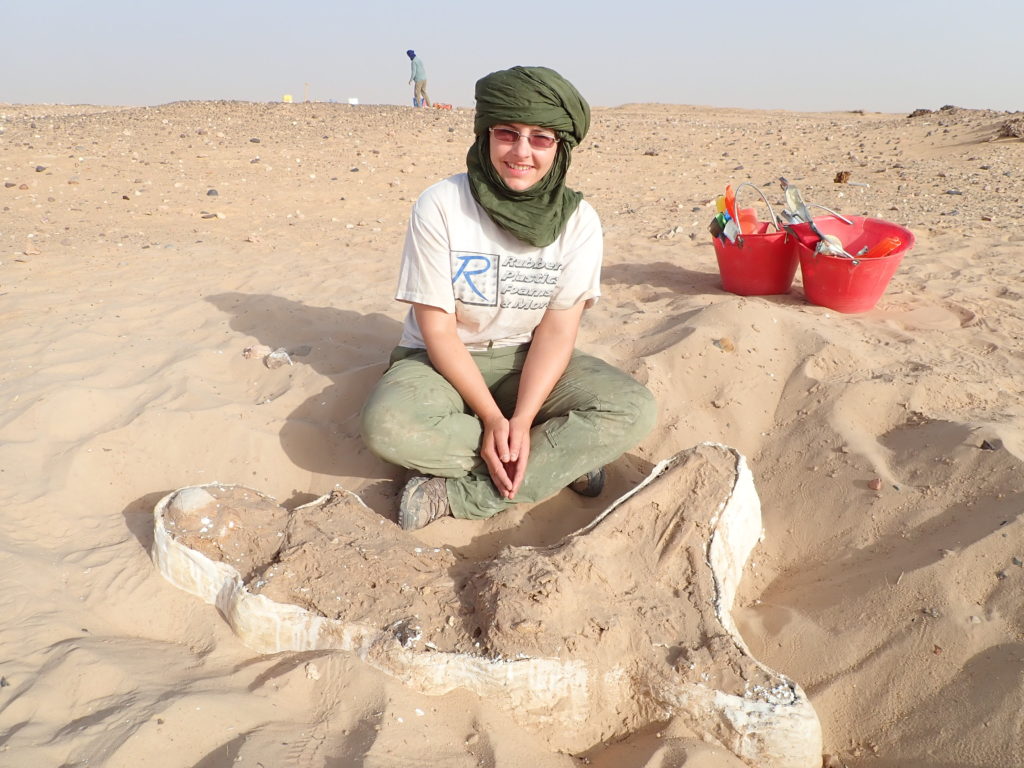

EF: So I work in the field of paleontology. Yeah. I am a fossil preparator. So we are considered like a lab technician in the realm of paleo. And so what I do basically is well, actually, first, I’ve been doing this for quite some time. I started volunteering in paleontology right when I graduated high school. It was like one of those things and some of my paleo friends at the Field Museum will attest to this, that I’m like the annoying kid when I’m 16, like, can I please play with fossils? And, you know, no, not until you’re 18. So when I was 18, I finally got to the museum and started working with fossils. And paleo is one of those fields where there’s not a lot of funding for it. You know, everyone loves dinosaurs and fossils, but you really have to express the importance of, say, what our job does for the bigger picture to get people to fund it type of thing. So most of our funding comes from people that love what we do. And so there’s a lot of room for people to come in and volunteer doing this. And that’s how I got started. And I’ve been doing it ever since then, and that was in 2000 when I started. So yeah, I’ve been doing this for quite some time. And so what I do basically is I help my boss. He is a scientist in paleontology and he decides where we’re going to be digging up fossils around the world. And I go and I help them do that. And as we bring these fossils back, I and a couple other preparators in our lab here in Chicago, open them up and we clean them and we get them all ready for scientists to study.

GW: So you how do you open them up? How do you clean them? What’s the process?

EF: So we have a series of tools and basically when we’re out in the field, how we dig out how we dig dinosaurs out of the ground, we create what we call jackets and where we have a process of encapsulating the bone along with the surrounding rock to bring it back safely. And it’s covered in layers of aluminum foil, plaster and burlap. And so when we bring these back to the lab, we have grinders that we can open up this shell, like a candy coated shell.

GW: So why do you wrap it? I mean, I get why you would want to sort of cover and preserve it, but presumably just like put it in a wooden box. I mean, why wrap it with aluminium foil? And I’m not trying to tell you how to do your job, I believe what you’re doing is no doubt the correct thing to do. But I don’t understand why you’d wrap it in either you foil or and then cover in plaster. That doesn’t make sense to me.

EF: Okay. So fossils are essentially bones that have turned to stone. And the fossils that that we dig up are about 65 million years or older. So we’re digging primarily dinosaur material. So you’re talking about, you know, 65 million years plus of time. So these bones don’t always look like bones anymore. They’re fragmented. They’re splintered. They’re in a lot of pieces. And sometimes you get a bone that’s pretty perfectly preserved but that’s more rare than not. So getting this material back without causing more damage is our utmost importance. So the aluminum foil is what we use as a separator, so the plaster will stick to the rock and the bone. So if we were to open this up, this shell that we have created would stick to everything and then make it very problematic to get off.

GW: So the aluminium foil is to keep the plaster and the bone separated. And the plaster is there basically just to hold everything still while you move it around.

EF: Yep.

GW: Okay. Right. Because otherwise the fragments would all mix up in different places. And you might not know where they came from.

EF: Definitely.

GW: All right. So I have an image in my head of, like, a femur which has which has been shattered. Like somebody had a nasty traffic accident or something. And so you have in the earth you have what you recognise as a femur with all these bone fragments and you want to keep everything in the same place relative to each other. And so you cover it up with foil. You’d have to dig out the whole bit of earth. And then wrap all of that in aluminium foil and then cover it all in plaster, let it all set. And then when you pick it up and move it, all the bits inside are going to stay where they are.

EF: Yes.

GW: Okay. Right now I get it.

EF: Now there is a process to how we get it out.

GW: Well, yeah. And how on earth do you do that?

EF: Yeah. So we first have to find the edges of the bone because most fossils that we will find are disarticulated. So they’re not, you know, the leg bone is a connected to the knee bone type of thing. That is very rare to have an animal articulated like that and that usually requires them to be buried very rapidly. They’re also prized specimens to be that way because then you know exactly what bone you have. And most bones are identifiable, say, for instance, you know, a femur versus a tibia or a fibula. But when you’re getting to your series of vertebra, you’ve got dozens of them. And how do you know what your D5 is from your D6, unless they’re articulated. And so there’s minor differences between these animals, sometimes. Sometimes there’s bigger differences. But how do you decide what species is what, based on maybe a couple of vertebra. So keeping everything together is important. So when we find an animal, when we find bones, we will look for the edges of where that skeleton is going to be. And because a lot of it’s disarticulated, you might have like a femur here and then maybe the lower leg bone maybe ten feet away. And so there’s a series of like digging around. And as you find the perimeter of these bones, even if they’re isolated, like, say, you have an isolated femur. You’d find the edge of it. And then we would add a consolidant to that. That’s either a water soluble consolidate or a more chemical, like an acetone based solvent that will keep it like a glue that’s archival. So an archival glue that keeps it together temporarily.

GW: So what’s it made of? I’m a woodworker, so I know a bit about glues and I know my hide glue from my polyvinyl acetate, from my ethyl vinyl acetate and so on. So what is what kind of glue would you use to kind of keep it all together?

EF: Yeah. So when we have access to, say, a chemical, the acetone, which evaporates pretty quickly, we will use a paraloid B72. And so that will allow it to soak into the bone. It’s archival and stable. It won’t degrade, at least not so much that we are aware of.

GW: So by archival, you mean it will remain stable for a very long time?

EF: Yeah. And reversible. So having something that’s reversible is also important to us because we want to be able to undo glue joints if we had to.

GW: Okay. Yeah. So you basically have this, like, acetone or water-based glue that is reversible and you soak that into the area to basically keep stick everything together.

EF: Yeah. Because, again, you know, earth is going to fragment. So as we’re trenching around these bones because now say we find a femur and the rest of the animal’s there too, maybe a couple of feet away. But the more or the less that we can get. It’s kind of a give or take, right? So if you take a whole femur out, like if you take a sauropod femur on the ground, this sauropod femur might be like six feet long. Like, that’s a huge chunk.

GW: That’s a big bone.

EF: Oh, yeah. So if we’re taking more than that, then we’re going to be requiring significantly more heavy equipment to get it out of the ground. So sometimes disarticulated bones works in our favour and sometimes it doesn’t. But if we’re going to trench around, we find this femur, we’re going to try to get that out of the ground. We would start by finding those edges, consolidating, and then we’re going to start trenching down. So we’ll start removing the rock around it to go down, and then we’re going to start putting a cap on it because now it’s going to start getting fragile. So we’ll put that tinfoil down, we’ll put that plaster in burlap coating, a couple layers of that until it’s pretty solid. And then we’ll start trenching down even more until we get down to where we can start undercutting the bone. And so our ultimate goal is to get the bone on a pedestal.

GW: Just to be clear. So you’re digging it out, you’re undercutting it. So you’re digging underneath the bone and you end up with basically a little pedestal of earth or rock or whatever that is sitting on it. And everything else is now being wrapped in tin foil and plaster has got this glue soaked through it. Okay.

EF: Yeah. Yeah.

GW: This is fascinating.

EF: And, yeah. So once we get it on a pedestal, particularly for large animals, it’s pretty safe to say there’s probably nothing directly underneath that femur. If there was, we would have found it by digging under it with our tools. And if there’s not, then once we have that pedestal, that mushroom shape pretty preserved and encapsulated, then we can crack the bottom and then roll it over. So once we get that pedestal cracked, then a whole bunch of us can get on one side, roll it on its back. And now we have the bone out of the ground, and now it’s upside down and then we just have to clean out whatever’s in the bottom because again, that earth, that superfluous earth there, is making weight. We want to try to get rid of some of that. And then we close it up and now we have a perfectly encased bone.

GW: Okay. And then you use whatever heavy lifting equipment you need to move it and transport it back to the museum. And then it’s there in the museum. And you get out your angle grinder, and you start cutting away the plaster.

EF: Yeah. Get our grinders out. Start cutting that out. So we kind of reverse what we did in the field, sort of, in a way.

GW: So I have to ask, how do you ever cut through the foil into the bone with your angle grinder?

EF: Am I supposed to admit to that?

GW: Okay. I’ve done a lot of kind of craft type stuff, woodwork mostly. And angle grinders are super hard to control really precisely.

EF: So mostly what we use, I’m trying to think of what an angle grinder is going to look like.

GW: It’s a rapidly spinning disk on a on a handle.

EF: Oh, okay. So then let me take that back. We don’t use angle grinders. We will use what we call a grinder, but there is a really, really large Dremel on the end of it. So maybe like a ball the size of a large marble. And that spins. And then so that we wouldn’t go any deeper than, say, the diameter of that ball. So yeah, certainly something that’s a disc would be dangerous for us because we can’t control how deep we’re going. So our plaster, depending on size of the bone like say for a femur, your plaster might be about a half an inch deep of coating around the bone. And so if you’re using like our Dremel bit, our larger Dremel bit grinders, you shouldn’t really go through too much of that. And your diameter, the line that you’re creating, that perimeter going around the jacket being the diameter of that bit, you can see how deep you’re going.

GW: Yeah, you can see what you’re doing.

EF: Yeah, you can see what you’re doing and that’s important. So anything thinner than that is really dangerous. So I mean, accidents happen, you know? Professionals like us make less of those mistakes than new people. And to be fair, we do take some of the earth with the bone. So if you are eyeing up the shape of the jacket and you’re going about partway down, like you’re not going to drill off the top because you know you’re going to hit bone. So you come around the side.

GW: Yeah. Okay, so you’re opening it up where you know it’s earth not bone.

EF: And sometimes you don’t always gauge it that well, but at least if you’re going to make a mistake it’s very minimal.

GW: Okay.

EF: Yeah. I mean, we don’t want to ever make mistakes, but.

GW: Yeah, but everyone makes mistakes.

EF: We’re only human, so.

GW: Yeah. Okay, so you have cracked open your plaster thing and you have basically the glue soaked bone and earth, and then what happens?

EF: So then we put it under a microscope and we have our specialised tools that are like little jackhammers, that are called air scribes. So it’s like a scribe used with a compressed air. So it’s like a really small hand jackhammer. So it’s got a little needle, maybe about sixteenths of an inch wide. Very small. And you keep it sharpened to a point, and then it kind of drills off the rock off of the bone. We do that under a microscope. And so that requires a bit of finesse.

GW: And if you’re using a microscope, you must be doing a very small area at any given time. And if your sauropod femur is six feet long, that is going to take you weeks.

EF: Yep.

GW: Wow. Yeah. Okay. Right.

EF: Yeah. I mean, if you were to see me work, you probably would not see me moving very much. Now I can see me moving quite a bit under the scope, but from not being under the scope, you probably wouldn’t notice me moving around very often. And you might get a couple of square inches of stuff prepared a day. And that depends on the quality of the bone and depends on the quality of the rock around it. We call that matrix. So the quality of the matrix, like some bones are very well-preserved. And so that rock around it flakes off pretty easily. And then sometimes it sticks, not even glue related, just sticks and that requires a slower process. And then sometimes you have a coating of haematite, which is like an iron. It’s an iron based mineral around the bone. And that stuff is, I hate to say hard as a rock, but yeah.

GW: So basically what you’re saying is that your job is not really a spectator sport.

EF: No.

GW: But it’s exactly the kind of job that all sorts of people, particularly like kids who mad about dinosaurs. They’re like, I want to be doing that. I want to be digging up dinosaur bones for a living. That’s my job. And it sounds like the actual job itself is much harder than it sounds.

EF: Well, so it depends on what job that you want, right? If you want the job of my boss who’s a paleontologist, you would need a Ph.D. for that. And you get to study dinosaur bones or any other fossil. But, you know, I mean, why not study dinosaur bones? I mean, they’re the best. Or you do what I do, which didn’t require a degree, but it requires experience. And then you can still be in paleontology without needing to have that formal education. And I feel like I just downgraded my job. But, you know, the reality of it is, most of the jobs, if you’re going to have a degree, would be to be the scientist. The scientists, naturally, would need a lab filled with staff.

GW: Right. Okay. And so what is your favourite bit of the job?

EF: Oh, I mean, I get to play with dinosaur bones all day. And part of what I like the most about, I mean, dinosaurs aside, right? What I find to be most fun about it is, is putting all the puzzle pieces together because it’s one giant puzzle.

GW: Right. Okay. So you’ve got your femur, which has been smashed by a T-Rex or something in a fight and you’re then trying to reassemble all these little tiny pieces of bone into what the original bone would have looked like.

EF: Yeah. And it’s maybe less about the death of the animal that gets these bones into little pieces and more about just erosion.

GW: Oh, sure. It’s much more glamorous to say, well, this thing got killed in a fight with a T-Rex. And that’s why the leg is broken or a rockslide 2 million years after the animal died smashed up the skeleton a bit. I mean, come on.

EF: Fair. You know what’s really cool, though, is when we do find evidence of traces of life left in the animal. So say bite marks or disease or fighting. So like claw marks and things like that. You know, Sue is the famous T-Rex here at the Field Museum. And she’s famous for a lot of things. One, she’s the oldest T-Rex, the largest T-Rex and the most complete T-Rex ever found. And if you ever come to Chicago, get a chance to see her. She has her own room now dedicated to her. And they go through and highlight certain aspects of her skeleton. And she has a lot of injuries that she had developed when she was alive. And then you could say suffer through, because I don’t think I would want any of those injuries. And lived to tell the tale. I think they’re still studying whether or not some of them actually contributed to her death. But she has a lot of evidence of fighting and surviving.

GW: Okay, evidence that would survive in fossil form must be damage to bone that’s then healed.

EF: Correct.

GW: Right. So T-Rexs could get on a broken wrist or something and survive long enough for that to heal completely. And then they get killed later by something else.

EF: Yeah.

GW: Wow. Huh. Because you sort of imagine that if a dinosaur gets at all injured, that it, it is just dead.

EF: If what?

GW: Is if a dinosaur gets injured at all, one would assume that it would just, you know, scavengers or predators or whatever would come and finish it off and not be that okay. In human remains, fossilised human remains, that same sort of evidence is used to support a story of human beings looking after their injured tribe members and nursing them back to health.

EF: Sure.

GW: I don’t think there’s a similar story going on with T-Rex, is that right?

EF: Not that we know of.

GW: Because that begs the question, why do we accept that as evidence of people looking after their injured tribe members? But we don’t accept the exact same fossil evidence of a broken bone that has clearly healed and therefore did not kill the person. Basically, the person who had their bone broken survived long enough for the bone to heal. That same evidence in a T-Rex isn’t used to support a story around T-Rexs actually living in herds and looking after their injured or damaged members.

EF: Yeah. I don’t know the answer to that.

GW: It is worth thinking about, isn’t it?

EF: Is. Well, I mean, it happens in nature now. You know, we change dinosaurs to regular wildlife nowadays. I mean, yeah, injured animals are certainly prey for other scavengers or people looking for a very quick, easy meal. But T-Rex at the time was the top of the food chain.

GW: Okay. So do we see do we see similar things like, for example, the lion is the top of this food chain, if a lion gets a broken leg or something, I don’t think they would be expected to survive without human intervention.

EF: Well, breaking a leg is a serious injury.

GW: Yeah. So what kind of injuries did Sue survive?

EF: I’m trying to recollect this. Sue does have some fused vertebra in her tail. I need to go back and look exactly what’s causing that.

GW: Okay. So we’re not talking about like a broken leg. It maybe be like a cracked rib that healed or a tail that wasn’t working quite right for a while and then healed.

EF: Yeah, yeah. I can’t imagine that an animal that would be requiring to either get away or require its legs for the use of catching its prey, having that broken, I mean, even a femur break in a human is a major, major problem.

GW: Yeah, it’s a life threatening condition.

EF: Oh, yeah. Yeah. I can only imagine it’s significantly worse for an animal.

GW: Okay. Well, this this conversation went in directions I was not expecting. This is fascinating. But I think we should probably because most people listening, like swords probably more than they like dinosaurs.

EF: I don’t know about that.

GW: Well given the topic of the show generally. So you’ve been doing historical martial arts for quite a while. I’ve known you for years, but what drew you to historical martial arts and how did that start?

EF: So I’ve always been doing martial arts. I was doing some judo back when I was in high school. So this idea of wanting to have fitness and then a sense of self-defence was always intriguing for me. What kind of got me into historical fencing that we do now was I think I remember asking my mom to buy me a book like, well, I mean, this would be cool because, I love the whole idea of fantasy and then what that is. And then loving that into a subset of just loving the medieval period and the renaissance and that type of idea of chivalry and pageantry. It was very intriguing for me. And so I had a friend again at the Field Museum who was like, oh, yeah, I’m learning how to do medieval longsword. And I was just like, you’re doing what? How did you how did you find that? Like, I don’t even know if I would have even considered looking for that in real time. Like I can find a book that people are maybe to learn it teaching this by book, but like there’s someone I can go to here in Chicago that will teach me that. And sure enough, there was and I think the next time that they offered that opening, I was like, boom, I signed up for it. And I’ve been doing that since then.

GW: So that was the Chicago Swordplay Guild. Who is the friend?

EF: Debbie Wagner. A friend of mine in Paleo, no less. So we have overlapping friends.

GW: And did your mom buy you the book?

EF: She did.

GW: What book was that?

EF: I prefer to not say.

GW: Oh I know what book that was.

EF: It’s the book that shall not be named.

GW: Right. Okay, good. Good, good. Yeah. Understood. Understood. Moving swiftly on.

EF: You don’t know any better at the time.

GW: If you’ve been in the historical martial arts world a long time, you know what we’re talking about. If you haven’t listeners and you really want to know, I will put it in very, very small font at the bottom of the show notes so that people have no idea what we’re talking about, can be kind of brought into the fold, but we’re not going to mention it on air.

EF: I feel bad I even said anything.

GW: You’ve been doing mostly medieval combat with the CSG, is that correct?

EF: That’s correct.

GW: Okay. And that’s your area of preference. Am I right? You never went into the Rapier or more modern stuff?

EF: I think I did Rapier. Certainly not the modern stuff. I did Rapier briefly to just help aid in the medieval side of the school. But, you know, the medieval track is my jam.

GW: Okay. So why medieval?

EF: Again, I just love the pageantry. I love the pageantry of armour. I love just the aesthetic of the clothing, the chivalry. And it’s not that I don’t get into the rest, surely enough Fiore is early renaissance already anyway but you know when you get into to see the rapier it’s just not, I mean the rapier is a beautiful weapon. And people that that are good at it make it look flawless. It’s just not my thing.

GW: That’s fair. I mean, some people don’t like dinosaurs.

EF: Oh, how could you say such a thing?

GW: It’s true. I’m very sorry, but it’s true. So, I mean, when I think of you swinging weapons around, I think of you in full plate armour.

EF: That’s awesome.

GW: That’s the mental image I have. And as you wouldn’t mind sending a photograph of you in your armour for the show notes because then people can see what kind of stuff you’re into. But do you actually prefer armoured combat to unarmoured?

EF: Oh, that is a tough question to answer. Yeah, I don’t know how to answer that. It’s a love/hate relationship with the armour. I love it anyway.

GW: Why do you hate the armour?

EF: Oh, because you’re wearing 65lb of steel. It can be cumbersome. It can be heavy. You can’t see anything through it, and it limits your mobility. So it certainly requires a level of fitness that if you falter on a little bit, that armour is just. I mean, I love it. Because, again, you get into that pageantry and I don’t know. I mean, I think wearing plate armour is pretty darn sexy.

GW: Well, when I put armour on, I just feel invulnerable. It’s like you’re six inches taller and ten times stronger, and someone swings a sword at your head you could just laugh in their face and let it bounce off your armour and gut them like a fish. That’s a feeling, right? It is a feeling.

EF: Although I don’t have I don’t have a full plate. Now, if I had full plate, like a little bit later period armour, I would feel more invulnerable. But I remember fighting my first deed in 2019. I fought in the deed at WMAW and I feel like I got my arse handed to me.

GW: You can say that, you can say whatever you want on the show. We have an explicit rating so you can say whatever the fuck you like. It’s fine. Excellent.

EF: I fucking love it. I really feel like I had my arse handed to me by now, what’s her name? One of Scott Farrell’s students. Her name escapes me now.

GW: Just pop it in an email. I’ll stick it in the show notes.

EF: Yeah, but she was in significantly more plate armour than I was. And I was like, I can’t get past these pieces of armour, but I had my belly completely exposed and just a lot of difference. And so if I had a fuller plate armour more a full plate armour, I would feel more invulnerable. I do feel a bit vulnerable, but not as invulnerable as I would like to.

GW: Yeah. I’ve never been particularly interested in like brigandines and like cloth armour or that kind of stuff. Like the full steel custom made to fit perfectly armour of gorgeousness. That kind of does it. All these sort of cheaper versions. It’s like, no, you’ve got to go full steel if you want to get that feeling of. Well, okay. I mean, like you said, your belly was exposed. So you didn’t have steel plates over your guts.

EF: Right. I didn’t have any folds or anything, no.

GW: Okay. So what were you wearing?

EF: I have a full mail shirt.

GW: Oh, okay. Yes, but a spear will go right through that.

EF: Right. And so will a sword point.

GW: It’s like showing up naked and you don’t want to do that. I mean, it’s not exactly modern technology, but you know, from the 1380s onwards, you know, those Milanese got their armour to the next level. So I think you should steal some dinosaur bones from one of the museums, sell them on the dinosaur black market and spend the money on proper armour.

EF: Wow. You just endorsed selling dinosaur bones on the black market.

GW: Well, because everyone can tell I’m completely serious. And whenever I plan crimes, I always do it in a public way like this and publish it on the Internet so that anyone can hear it and go, oh, that’s a jolly good wheeze for a crime.

EF: So when he really does it, there’s no way he’s serious about that because he just gave it away.

GW: Exactly. Exactly. So it couldn’t possibly be me.

EF: Yeah. But, I believe my armour is early Milanese. So it is right there around 1390, doesn’t have the folds, but I guess I could have the folds. But I’m a wee little person. So if I decide I’m going to add on to my armour, I gotta build up to that for sure.

GW: Yeah. And you’ve got to get somebody to make it really fit. That makes all the difference.

EF: It does. That’s the other thing is that if your armour doesn’t fit well, it’s miserable to be in.

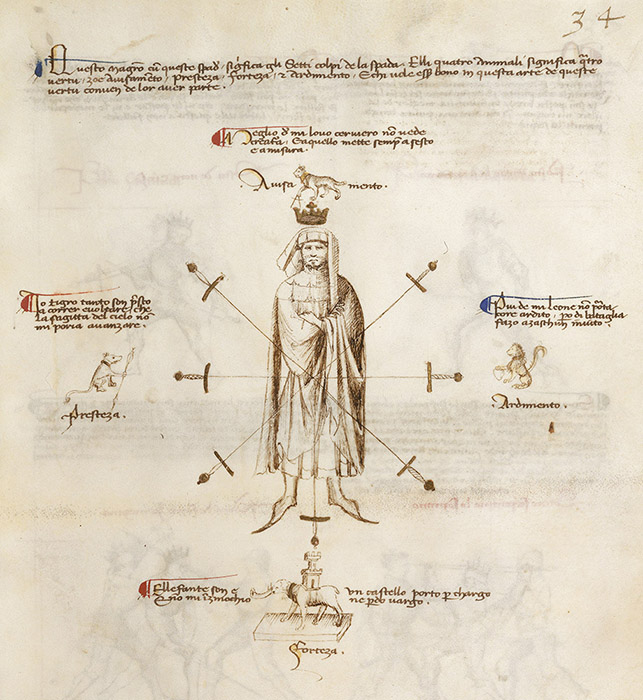

GW: So I’ve seen a picture of this astonishing version of Fiore’s Segno Page. What is the story there?

EF: So obviously I ended up getting my degree in art. So I am an artist and a lover of dinosaurs when I was a wee little kid. So, when I went up for my Free Scholar rank at the CSG, I had proposed to Greg Mele our instructor, we have to do a series of papers and we have to do like a big research project to rank up. And I had requested, can I do something art based. And he said, yeah, I would love to have a big picture of like a Segno in the studio, like a life size Fiore size Segno. And I said, well, that’s going to be quite large because, if you want the whole Segno, not only do you have to have Fiore the guy in the centre to be the size of Fiore. Then you have to add on all the animals. And so we ended up not quite getting it that big because that might have been almost too big. So basically over two years, I researched a bit about the Segno and we actually put together the animals from the Pisani Dossi with the Fiore from the Getty and we merged those two Segnos together and created a colour version of the Segno to have up as a teaching tool. So not only does it make for a lovely centrepiece for the studio, but it’s a teaching tool. So when Greg wants to talk about what the Segno means and how we use the Segno in swordplay, he’ll refer to that. But yeah, so I did that for my main project.

GW: Okay. So what is that on. Is it just a giant piece of paper or cloth or how did you do it?

EF: It’s on canvas. And originally we wanted to hang it like a tapestry. That ended up about a couple of years later causing some damage, which I will never do that again.

GW: How do you mean, hang it like a tapestry and causing damage?

EF: We hemmed it and then put loops in there to have bars so that we could hang it from the wall like a tapestry would hang, like a cloth tapestry. Didn’t go so well for canvas and oil paint. Did a little bit of warping and cracking.

GW: So basically the picture is oil on canvas, correct?

EF: Right.

GW: And if you hang it like a tapestry is going to put folds and things in the cloth.

EF: It didn’t exactly put folds in it. It just started to warp a little bit like a bit of the humidity contributed to it.

GW: Because normally with an oil painting the canvas would be stretched on the frame.

EF: True. True. I have seen plenty of oil paintings that are not stretched, that are typically rolled up. And I had a lot of advice. I got advice from some professional paint companies about it, and they said, we don’t advise doing it this way. I guess you could. And if you’re going to, here’s what you would do. But we still don’t advise it. And I should have just listened to them.

GW: Okay. So how is it hung now?

EF: It’s stretched. We ended up stretching it.

GW: Okay. So you built a frame around it and stretched it on that. Okay, that makes sense.

EF: And then I repaired it, and now it’s hanging back up in the studio.

GW: So you painted it, I mean, presumably you didn’t have an easel big enough to stretch the whole thing out on at once. So you must have painted it sort of bit by bit.

EF: Yeah. So I basically took my closet in my apartment, because I have cats, and oil painting and turpentine and mineral spirits, and that’s pretty toxic. I essentially kind of dismantled my closet and designated one whole wall to this canvas, which basically took up the whole wall. And I would go in there and once I had had it up, I would transfer the image and then paint it. And it took me about maybe about a year and a half to paint, and I would paint a little bit at a time.

GW: How did you transfer the image?

EF: I did it with a grid.

GW: Okay. So you didn’t project it. You just had a grid of squares and just tracked it that way?

EF: Yeah. So what I tend to do is I blow up my drawing to scale, and I print out the sections that I need to transfer. And then I grid the image, and then I grid the canvas, and then I transfer the drawing that way. And some things that I will have drawn in my programme, I digitally draw everything first, and then I’ll print it at scale, and then I will trace that onto the image as well. Or onto the canvas.

GW: That’s quite a process. Did you copy the text over and if so, was it the Pisani Dossi text or the Getty text?

EF: There’s no text.

GW: There’s no text. Okay.

EF: Just the animals and Fiore. And then I completed it with a border to look a little bit like a manuscript page. So a majority of my research that took place was studying the design of Fiore’s border design in his books. And they’re a little bit different amongst the different books. But then I would pull a lot of the design that I find Fiore to be. At least whoever is painting his manuscripts seem to be coming from a Bologna school, or at least inspiration from the Bologna tradition, or the Bolognese tradition. So I would take other illumination from his time period in Bologna and then kind of piece together certain aspects that would fit in a space. And that’s how I came up with that border design and then other symbolism. So I put the five petal rose in the design as well to be very symbolic.

GW: Why particularly the five petal rose?

EF: I wish I had my notes that I could pull from, but there’s a certain level of the Rosicrucian rose that has symbolism for the number five, for being the number of man. So the symbolism in the Segno is all numerology anyway. So you have the elements, you have the number four and then you have Fiore, which represents number five. And he would be the fifth element for quintessence.

GW: Did you include the crowns, by the way?

EF: I did.

GW: Because if you add in all the crowns and collars on the animals, you get, I think, 12 pieces of gold. There’s the sword hilts and there’s the crowds and stuff. There’s all sorts of things. When you look at the version of the Getty manuscript, at least, all the numbers he’s used so far, like the eight things you must know for the abrazare, and the five things for the dagger and the nine masters of the dagger and the 12 guards of the long sword and the seventh plays of the sword. You can use the various elements of the Segno like a memory palace to hold those groups together.

EF: Yes. Correct me if I’m wrong. I don’t think the animals have crowns, though. Correct?

GW: The animals don’t have crowns, but they have gold collars.

EF: Yeah. So they have the gold collars. Yeah. So everything was transferred over. So you have the four animal collars, you have Fiore’s crown. So that makes five and then you have seven of the sword hilts.

GW: Yes. That’s 12 together. Yeah, it’s quite a thing because I just went and grabbed my facsimile of the thing just to have a look. And of course, we will be putting a picture of the original Segno from the Getty manuscript in the show notes. But also you will, I hope, send me a decent picture of your amazing Segno so we can stick that in the show notes so people can see what we’re talking about.

EF: And I used a 24 karat gold leaf on them as well.

GW: Oh, my God. How did you apply that to an oil painting?

EF: To a flexible oil gilding glue. The adhesive isn’t oil based, but it’s flexible. So it would have worked for putting it on canvas so wouldn’t be on anything like, say, wood.

GW: Wow. Okay. That is a hell of a project.

EF: Yeah. And it’s in colour, so now it’s like oil paints. And then I had a conversation with Tasha Mele about what would Fiore be wearing. Like, what’s he wearing and what colours would they likely be.

GW: I think most listeners probably don’t know Tasha and therefore aren’t aware that she probably knows more about medieval armour clothing than anybody else on the planet.

EF: Yeah, she’s amazing.

GW: And Mele’s her married name. Before that she was Tasha Kelly.

EF: Tasha Kelly.

GW: Yeah. Okay. So you can find papers she’s written under that name, I would guess.

EF: Definitely, yeah. And I think we even have a link. She actually did a whole blog on her blog site about the project she did with me for the Segno. So I can give you a link to that.

GW: By all means send me a link. People are going to get a lot of stuff in these show notes, it’s great.

EF: Yeah, exactly right. All this education.

GW: Yeah. Okay, so just a slight, slight detour. I know you’ve travelled a lot because we had a bit of difficulty scheduling this because you were gallivanting around France and what have you. And I imagine some of that travel is for work, finding dinosaur bones and some of that is for just fun.

EF: For a vacation.

GW: Yeah. So travel is obviously a really important part of your life. What does it give you?

EF: You know I have two times that I’ve travelled that I’ve been the most influential on me and one was in 2000. My mother did a family trip, like a tour of, like Hungary, Austria and Germany. And before that, I mean, I had been to Canada. I think I was a wee little kid, though. I mean, I don’t remember much of it, but other than that, I had never been out of the country before. I was 18 and on this really neat tour of Europe. And it was just very cool to see how other people did things. And of course, at the time, again, I was into fantasy and medieval things then too. So I got to see like old castles and got to museums and see some of their armour collection and the weapons and their on display. And it was just a very unique experience for someone who never done that before. And after that, I started to kind of get a little bit of the travel bug of like when I got to be old enough to have out of school and graduate and have a job and have money, because you need that to travel, and actually finally get out and do things. And when I started working for the University of Chicago, that’s where I work now, working in paleontology, I got to travel for conferences and give talks about what I do at work. And that just was opportunities to go around the world without having to cost me really an arm and a leg because it’s kind of covered, right? So when my boss, Dr. Paul Sereno, he did most of his digging over in Niger in Africa, started in the early nineties. And he’s been trying to plan large excavation trips out there ever since. And I had asked if I could go in 2011, and that trip was for six weeks. It was probably my most influential trip I’ve ever taken in my life, I would say, because at that point, I may be going for work, but I’m going for an extended period of time where I’m living in an undeveloped country where you really get to see really how other people live in the world that you are very not accustomed to. How they get their food and what do they do with their time. And they don’t even have close to the amount of resources or money that we have here or opportunities and things like that. And just what are they doing? And I ended up coming home thinking these are some of the nicest people ever met in my life. And that kind of changed quite a bit of my worldview. And ever since then, I need to do more of that. I want to go to more places like that. And I’m not sure the kind of saying I’m trying to think of, but I would go anywhere just for the experience.

GW: Just to see.

EF: Just to see. And we went back in 2018 to the same site, and we were there for two months. And I made some friends along the way, and I still keep in touch with them.

GW: It is fundamentally different living in a place for weeks at a time than just visiting it for a few days. It’s not just you get to do more of the stuff, it’s like you sink through the surface layer and you start to see the layer underneath and then the layer underneath. I was learning things about Finnish culture after living that for five years that you cannot possibly learn just by going there for a week.

EF: And it’s interesting because when I travel, I mean, I’m a tourist, obviously, but I try to not travel totally like a tourist, I don’t really want to do tours. I don’t really want to stay in hotels. I would rather stay in places that locals might stay or eat at places locals will want to eat. We were just in Morocco last month and we did book basically a private tour to have someone just drive us for four days out to these different locations. Because I wasn’t going to try to do the logistics together on my own, but it was like, no, just take us where you think. Where would you guys go? One day we were just very exhausted. We were out in the desert and we were very exhausted. We were just let’s just take the day off and he took us to this little Berber village. We had this all this time to kill. He just took us this Berber village, and we got to have mint tea with her and her family in her little house. And we just got to see her bake her bread in little clay oven that they make out of out of the ground and see their goats. You just don’t get to see this on a normal basis. And that’s the kind of thing that I want to go see. I don’t need to go see all the things that these tourists want to be catered to.

GW: Yeah. On my first trip to New Zealand I took a few days to go to Rotorua, which is this area of this town where they have these amazing hot springs and everything. It’s fantastic.

EF: I’ve been there.

GW: Yeah. All right. And they have this amazing kind of Māori culture thing set up for the tourists. And it is great. It is definitely worth looking at. But, one night when I was there, I was just wandering about and I was there on my own, I was just wandering about and I just went into a restaurant because I was hungry. And it was one of these sort of all you can eat, go back to the buffet thing. I think it was Mongolian barbecue kind of place. And while I happened to be sitting there just having dinner maybe 50 or 60 Māori people came in for a birthday party for a member of the family. This kid was 21 and that’s a huge thing, kind of like 18 for us, I guess. And it was this Māori kid’s 21st birthday party and I was just sitting there in the restaurant and they got up and they did all kinds of like traditional singing. It wasn’t for the tourists. It was for their person who they loved. It was fundamentally different. I just happened to be sitting there. I just happened to be experiencing this window into a culture I know nothing about, that wasn’t created for foreigners to look at. It was them doing it for themselves.

EF: Sure.

GW: Fundamentally different.

EF: Yeah. It’s those kinds of things that I find to be significantly more memorable. And a sense of the culture, too, when you’re when you’re out there. We had a similar experience at the end of our 2018 trip in Niger too, a friend of mine, we were in one of the hotels in Agadez, and we could hear this music going on in the background. And I said, oh, let’s just go check it out. They don’t want us to go wandering off on our own, but you can go off with a couple of us at a time. And so we went out and across the street and down the street there is all this commotion. We were like, oh, what’s going on? Like, oh, you know, my son is getting married and she’s like, “Come on in.” We’re like, okay, no, no, no. “Just come on in.” And okay. So we went in and we just got to there is this Tuareg wedding happening in this fantastic little complex. And we got to see so much of what you just you just don’t know. And they they’re like, go, go, go dance. And, like, we don’t know how to dance the way they’re doing their thing. But you improvise and everyone just had a great time. Everyone just loved it. It was very, very unique.

GW: So there are a couple of questions I ask all of my guests. And let’s go to the first one. Now, you’ve done quite a lot of things and I guess most critically acted on your dinosaur obsession. But what is the best idea you haven’t acted on?

EF: Oh, I think one thing that I always thought would be really cool to do would be to be a medieval innkeeper.

GW: A medieval innkeeper. Okay.

EF: I always thought it would be so cool to just have, like, a unique hotel experience, but have it be like if I were to be the innkeeper, right? I would get to be in medieval garb all day long, which I think is fun and have a have some type of tavern that would have similar things to maybe what we would think a medieval tavern would be like and you could have animals. I would want, I don’t know, camels. Like, weird things that I just love having. Like, camels or llamas or goats. But like to have music and your fire going. And it would be a cool place to have, like if it was here in Chicago, I would envision it as like a place so if people were to stay at this inn, they’d have a bit of a medieval experience with like pigeon pie and stews and these medieval type foods and ale and things like that. And then you could have like this thing out in the side where people are fencing or there’s a tournament going on. That just seems like so neat. It’d be like can you imagine having a hotel where it’s like a bunch of hobbit holes, I would definitely stay there.

GW: I’ve been to sort of medieval themed restaurants. You’re thinking of something a bit more immersive, a bit more three dimensional?

EF: Yeah, a little more authentic. It’s interesting, like when I talk to people about, like, going to Africa, digging dinosaurs, just like that sounds cool. And then when I talk about they’re like, I wouldn’t want to do that. That sounds horrible, you know? But for the experience, right? I think that might be a little similar to this medieval tavern, it’s like, well, if you want the real medieval tavern experience, people may not want to actually come, but I think that would be the cool part about it.

GW: I think people might come, to make the food really authentic is quite hard because I guess if we’re talking probably medieval, then you won’t have anything, any foods from the new world so no potatoes, no tomatoes, no chillies. That’s a bit restrictive. But there’s amazing medieval food to be had. So long as I guess it’s safe. So you’re not going to get a dose of plague with your porridge.

EF: That would be a very medieval experience.

GW: But maybe not. Also you probably don’t want the likelihood of like bedbugs and body lice and things like that.

EF: Okay. No, we don’t want to get too authentic.

GW: But it would be a very cool idea to have a fencing area. I mean, traditionally, there are plenty of examples of fencing schools which were attached to brothels. I don’t think you’re talking about a brothel.

EF: No, no, no, no.

GW: So they leave the brothel bit out of it. But the food and the drink, yes, the buxom wenches, no. But yeah. So having an area so diners could watch the fencing or maybe take part of the fencing, if not too pissed. Yeah, that’s not a bad idea. Do you think you’re actually going to act on that?

EF: No.

GW: Why not?

EF: Well, I don’t have the kind of money to do that, nor the free time. It’s one of those things where it falls in that realm to me of you would do it for the fun of it, you know? But it’s interesting because I think when we were in Germany, at some point we went to maybe it was like one of the oldest bars in Germany, if not the oldest bar. It was like over a thousand years old and still running, but it was like packed. It was just like it’s a cool thing to go do. Maybe similar to that, although certainly minus the actual historical authenticity of it. It’s not really a thousand year old tavern, but you know, it’s one of those things where if it didn’t work out, would I be okay with that kind of loss? Like, I don’t know. It would be like quitting my job and then being a full time innkeeper, which sounds great. I just always think the thing requires money.

GW: Also, I’m not sure that the personality traits that make for a good fossil preparator would necessarily make for a good innkeeper.

EF: It’s possible.

GW: Because I’m imagining that you have to be very meticulous. You have to be very organised. That’s not a bad thing for an innkeeper either, but primarily innkeepers have to be able to manage social interactions between drunk people.

EF: Yeah. I don’t know if I’d be that good at doing that. I’ll just hire someone to do that.

GW: Yeah, maybe. Then maybe you could be the proprietor but have a manager.

EF: Exactly. Yeah. You got it.

GW: Yeah. Get the CSG in as bouncers, that would help.

EF: Yeah, for sure.

GW: Okay. So I’m guessing that if somebody did give you $1,000,000 to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide, you wouldn’t actually spend it on your inn, is that right?

EF: No, no, no.

GW: How would you spend it?

EF: I would spend it on research. I would spend it on two things. I would spend it on research. Because I think that there’s a ton of things that we just don’t know.

GW: Okay. What kind of research? I mean, what would you actually spend the money on? Would it be hiring academics to do certain kinds of research or creating a journal to publish that kind of research or?

EF: I didn’t think about that, but actually a journal for publishing that would be great.

GW: We do have one: Acta Periodica Duellatorum. But it doesn’t seem to have a lot of traction.

EF: Well. You might say that we’re a small group of personal researchers in the in the realm of that type of historical material, no?

GW: I’m thinking where’s the money going to go? Are you going to pay academics or offer scholarships?

EF: So, like two things. One for the academic side of it. I would want to put money into paying scholars to do the research. I think one of the best things that happened at least for what we study is that everything got digitised.

GW: Sure.

EF: You know, I think having access like a public domain to have it for regular Joe folks to have access to this without having to go to the Getty Museum.

GW: Yeah. We have Wiktenauer. So would you give that chunk of money to Wiktenauer?

EF: I wouldn’t want to give it to Wiktenauer. I would give it to museums that are actively going in and doing that kind of research, whether they’re doing excavations, whether they’re seeking out private collections that would allow us to have access and to study that material. So it would be going into museums, scholarships for maybe students that are doing master’s programmes or Ph.D. programmes in that field for that type of research to actually give us some concrete information on if we want to research something ourselves, where do we go for that? I mean, yeah, we could go to Wiktenauer for that, but who does the work that gets it to Wiktenauer?

GW: Like scanning it and finding the original documents and scanning them in.

EF: Yeah, like, for example, like the Florius was found in our time of study.

GW: 2010.

EF: Yes. So to find that in our time is pretty darn cool. I mean, there’s got to be more. There might be more. There may not be, but there might be. And we won’t know until more people are actively looking for that. And so I would want to put money to that. And then the other side of it is to put money into scholarships for actual training for students that can’t afford to go to say VISS or WMAW or other events that would have access to other masters that do this, other educators. Because I learn great things from Greg as my instructor, but I also learn great things from you or Sean Hayes or Christian Cameron that have maybe slightly different ways of viewing things that actually does a lot of things, but expands our repertoire and how we view things and helps us to process that information and learn from it different than what our core instructor might be teaching us. It just gives us more information. And I think students that may not have the ability to get that type of instruction, I think, miss something.

GW: Yeah, absolutely. Getting students basically to get exposed to different instructors in different fields. What I used to do when I was running my school in Helsinki is I would bring instructors over, maybe four instructors a year. So my students were continually exposed to lots of different instructors for exactly that reason. And that was a lot more efficient than sending my students over to these various events. We did that as well. But it’s much easier to move one person across the planet and have them teach I don’t know 30 people for two days than it is to move the 30 people across so they can get taught by the one. So that’s how I approached that same problem for my students. But yes, making the students themselves more mobile is also a good way to do it because when you go to an event like WMAW or Swordsquatch or whatever and you kind of see all these different things all at once, that has its own particular magic to it.

EF: It does. When you’re meeting other students, you’re meeting students from other schools. And that builds a certain amount of camaraderie and friendship.

GW: Yeah.

EF: Yeah. Relationships and it is just not something everyone has the opportunity to have something.

GW: Okay. So you say you’d split the money between academic research and scholarships for students of historical martial arts to travel to events and whatnot.

EF: Yeah.

GW: Most people go with one side of that or the other and you just decided that it’s imaginary money and I can have as much as I like and you’re going to do both.

EF: I mean, there’s two sides of that coin, right? There’s either the people that are doing the studying or there’s people that do the research and then there’s the folks that actually train it in application.

GW: Yeah, hit both. Why not?

EF: Yeah. Yeah.

GW: Excellent. Well, thank you so much for joining me today, Erin. It’s been lovely seeing you again.

EF: Yeah, thanks so much. And it was a pleasure being on here.