GW: Hi sword people and welcome to this episode of The Sword Guy, I am your host of this show. My name is Guy Windsor and I’ve been teaching and researching historical martial arts for an extremely long time. Now, normally, this section of the show is where I tell you about some courses or book that I have produced that I need you to go and buy so I can keep producing the show and keep feeding my children. But in this case, I want to draw your attention to the Wiktenauer project. So the Wiktenauer is this gargantuan online repository of historical martial arts resources. So, treatises and articles upon those treatises, high resolution scans, all sorts of things. When I’m working on any of my technical books, any of my research books, I use it pretty much daily and it is a simply monumental undertaking. The person responsible for it is Michael Chidester and he is actually on Episode 21 of this very show. He recently started a Patreon account at www.patreon.com/MichaelChidester. And I would plead with you that you go and you support Michael because he’s using the money to make historical martial arts a much more viable proposition for everybody on the planet. It’s a fantastic free resource. If the Internet was on fire and I could only save one historical martial arts resource, it would be the Wiktenauer. No question. All of my stuff could go burn because the Wiktenauer is where we have this glorious library and repository of sources and scholarship upon those sources. So please, if you feel like supporting historical martial arts, go along to www.patreon.com/MichaelChidester and be as generous as you can. Thank you. Now on with the show.

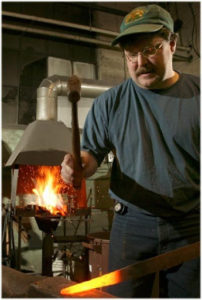

Hello sword people, this is Guy Windsor, also known as The Sword Guy, and I’m here today with Craig Johnson, who is a sword maker who runs Arms and Armor, which is one of my favourite suppliers of swords. www.arms-n-armor.com. And he’s also secretary of the Oakeshott Institute, which means he has legendary sword collector Ewart Oakeshott’s entire collection to play with. And in fact, probably half of the experiences I’ve had of holding original swords can be laid at Craig’s feet because he was there with a great big bag of the things and he let us play. So without further ado, Craig, welcome to the show.

CJ: Thanks for having me.

GW: It’s lovely to see you again. So just to orient everyone, whereabouts are you?

CJ: Minneapolis, Minnesota, hub of the sword world. A little cold today. But we’re doing OK.

GW: Excellent. Now your day job is something of a kind of dream or an aspiration for many people, some of whom are listening to the show. So you make swords all day. Is that correct?

CJ: I try to. We’ve got a shop with about seven people and we launched a brand new website about a year ago. So much more of my day sometimes is wrapped up in administration and paying attention to social media and things like that than I used to. I prefer making swords all day.

GW: So how did that come about? I mean, how does one become a professional maker of swords? How did you do it?

CJ: OK, a firm commitment to the ideal that I had a liberal arts education and thought I could make money doing anything. After that it’s a long and winding road. I was really interested in this stuff because of probably Errol Flynn movies in the afternoon after school and grade school, Robin Hood, that kind of stuff. And I was just always after that kind of thing. So my brothers and I were making bows and arrows and swords in the sumac around our house and having fights with bows and arrows and swords. And we always paid attention to that kind of history and studied it. I went through college and came out with a social studies, history and political science degree, and was trying to find a job teaching in schools and was working in construction, took tax advice from the construction crew and suddenly had to have a real job. And in college, I had met Chris, who owns Arms and Armor, and a guy at his booth had taught me how to make mail. In a Shakespeare class in college, I tried to get out of doing a five page paper by doing a project, i.e. completing a mail shirt. Not a good trade!

GW: It takes less time to write five pages.

CJ: I spent almost three solid days during a blizzard in Fargo, North Dakota, finishing it, but I kind of became legend in the Shakespeare class because the teacher would always reference it for years after. So I did that. I got a mail shirt and had talked with Chris about swapping a mail shirt for a sword and just continued that connection. I was kind of helping him out in his shop, doing little jobs, he was teaching me how to make a helmet. I went into his place the next day and he had just got off the phone with Hank Reynard at Atlantic Cutlery. And they had just signed for the first order where we were supplying some of the Atlantic Cutlery’s impact weapons. And I went to ask for a job and he said, “You want a job?” before I could ask. So that’s how I started. And from there, I started making armour, started making weapons, swords. We got into the Renaissance fairs as a venue to sell. And Chris, we got into those doing a joust act and we started doing a joust act in Minnesota. So my first combat experiences were fully armoured on horse combat back in the ‘80s.

GW: Back before health and safety.

CJ: Yeah, well, our main target was hit him in the head, the helmet. We can’t hurt each other.

GW: So basically, Chris Poor taught you how to make swords. Is that correct?

CJ: Yeah. Well, we’ve learnt a great deal along the way. When we first were making swords, we were making swords as we thought they were. Chris had some access to certain original pieces, especially Asian stuff, because of his father, who was a professor of ancient Chinese bronzes. But Chris, as a teenager or young man, even, got a gift from his dad of a Japanese armour original.

GW: Wow.

CJ: I know. But, you know, we were always around artefacts and stuff. And I never thought that we knew what we were doing, in the sense of we know exactly how this is done, but we’re always trying to do it better. So we had an invite to a trip to England to do research and we had an invite to Ewart Oakeshott’s house with a fellow. That fellow backed out of the trip right at the end, so Chris and I just went to all the places we were scheduled to go and just introduced ourselves and said, “Sorry, we’re just showing up, but this guy begged on us and we still want to meet you.” And that’s where we met Ewart, and David Edge at the Wallace Collection. We met a collector out in almost into Wales who had one of the two swords that I consider my golden swords or the swords that I would love to have someday. This was a hand and a half, thin, single edged blade with an eight inch back tip edge on it and a roped guard with side rings and a kind of squashed pincushion pommel, very thin little grip on it. But the blade was inscribed Siege of Rome 1580 or something like that. It was literally a sword that somebody had used in the defence or attack of Rome. When you get to sit there and sip whisky and tea in front of a 13th century fireplace in their little cottage with that sword on your knee, that changes you genetically I think. You start losing thoughts of, “I’m going to be successful monetarily doing this.” and you just focus on “This is cool.”

GW: I have to say, if there is one abiding thread to everything we’ve been doing for the last 20 years, it’s swords are cool. And there is no need for further explanation than that. That is a complete justification for what we do.

CJ: If that doesn’t make sense with you, you don’t get it.

GW: Exactly. So you met Ewart Oakeshott on this trip?

CJ: Yeah. He was one of the coolest human beings we ever met. We became friends, continued for years to interact and help out, and near the end, when he and Sybille were getting fairly old, Chris and I would go over periodically and stay with them for a given amount of time to help some of the caregivers have a break and stuff, so literally just were scholars at the foot of a great teacher trying to help out as best we could. And as his life came to the end, they were trying to decide what to do with the collection, and he had certain ideas about how he wanted it to continue on. And we were striving to help him find someplace that would do that. And that was a difficult task.

GW: What were the ideas?

CJ: Well, he didn’t want it in a glass box someplace that no one could ever touch. He thought they were objects that were in his care for just a while and that they should go again to be able to be used and to educate, to teach people about the past and what they were as objects and to understand them. I mean, when you pick up a really old sword, you start to understand in ways that you can’t unless you have that physical experience, how refined a three and a half foot steel fillet knife can be. They are created with an objective and a knowledge that we don’t have. These are lethal weapons, and so there’s not many people out there with that kind of experiential understanding of the object as they had, and so we have to let those pieces teach us and he was very much of that idea. So he wanted it as kept together as a collection, if possible, because he wanted it to be used as a way to understand his typology, because these are some of the swords that helped create it. And then he wanted it to be used to give other people that experience. He didn’t want it behind a glass wall that you couldn’t touch except in very rare instances.

GW: I’ve been at events where you’ve shown up with two enormous boxes, absolutely crammed with swords dating back… I think the oldest one was about three thousand years old. And then you were just handing them out to people to feel what it feels like to hold the thing. It is an experience where until you’ve actually had the experience, you don’t understand how important it is. It’s what you were saying. The heft of the object gives you its purpose. I only really understood Cappoferro’s guard position with the weight on the back leg and you’re kind of leaning back and your face is held back when I went to the Wallace Collection and David Edge very kindly got out a bunch of swords for me. And I had a friend along with me and I put a rapier into my friend’s hand and told him to point it at me. And then I tried to approach him to stringer. I was holding an antique and he was holding an antique. For the first time ever, I naturally adopted Cappoferro’s guard position. It was just like I want my face as far away from that thing as possible. I want my sword as close to his sword as possible. How do I do it? Oh, my God, I’m in the guard position, how the hell did that happen?

CJ: Yeah, that’s the essence of what motivates me. Those “A Ha” moments. And I’ve had several over the years where an object teaches me something. When I’m like, oh, I’m so stupid. Human beings are so stupid. We think we know what we’re doing and we don’t.

GW: I remember a backsword that you brought to one event or another, I forget which. I put my hand in the guard. This is like an early 19th, possibly mid 18th century backsword with a very small basket. And it was like some kind of sci fi weapon where the protective shield kind of ripples out, moulds itself around your hand and then sets because once my hand was in there, I would have to deliberately let go of the weapon to drop it and just relaxing my hand completely like, let’s say somebody whacked me in the arm with a stick and I had no feeling in my hand at all, the sword would not have dropped. It required literally nothing in my fingers at all to keep the sword attached to my hand. It was like, oh, my God. That’s how I want my backswords to feel.

CJ: They should feel like they’re extensions of your hand. When you point a finger, that’s where the point should be. And if I bring my hand to the side to protect myself, the blade should flow there.

GW: The claymore that you made for me 15 years ago for my book, The Duellist’s Companion, it still does that. I pick it up, it’s like I’m pointing with my finger and the point just goes exactly what I want it to go. In case you are wondering whether you ever hit that ideal, let me assure you that you have.

CJ: I try. That’s the challenge. Every modern maker probably has to deal with this in their own way. It’s the kind of thing Peter and I talk about a lot.

GW: Peter Johnson?

CJ: Yeah. The brother of another mother. Do you build to the ideal of the original, do you build to the exactness of the original, or do you build to what the customer is asking for, which you realise is not anywhere close to the original? And that’s a choice you have to make.

GW: What do you do?

CJ: I always advocate for they knew what they were doing way better than we did. So using their examples is probably the best choice, because they understood it on a level we will never. This is something you run into quite a bit, doing reproduction and training weapons especially, is there’s that golden moment where you have been training with swords for three to eight months. And you have maybe an epiphany moment or an idea tinks in your back of your brain and suddenly you feel like you’ve got an insight on swordplay that no one has ever had before, and if you had a weapon that was like this, you could do whatever, and that’s not true.

GW: Because if you know what you are doing, any decent sword will work just fine.

CJ: Yeah, human beings have been doing this for thousands and thousands of years. And when they were making them back then, it was the Einsteins and the Elon Musks that were doing weapons, armour and that kind of stuff and trying to take the physical materials and create something beyond the edge of the doable. So your insight as a new sword fighter is great for you, and that’s a motivational thing, but we have to understand that anything we think of has been thought of probably about eight times before at least, and tried and abandoned.

GW: Although we have much better quality steel and we have much finer tolerances in manufacturing. So would old swords actually be better than the swords that have been made now?

CJ: It depends on what you’re defining as better. Material wise – yes. The steely iron mix of original swords is something that I get in the weeds about, but is very much the kind of thing like your grandma used to make cookies, pinch of this, pinch of that, and it was never quite exactly the same amount. But they always taste delicious, right? Where today you can go and buy a cookie in a package at the gas station and it’s super cheap and you open it up and it’s exactly the same every time. And it tastes like cardboard. So the materials, yes, are way better now, but just because your materials are better doesn’t mean you can make the design any less. If that makes sense.

GW: The material quality doesn’t necessarily compensate for design flaws.

CJ: Right, right. So we have steels today that are dialled in. We know exactly what’s in there. We have temperature controls to within a degree or two, all of these things we know exactly what’s happening. When we quench something, we quench it with very specific materials and times to create something that is right up to the edge of our design envelope in a sense of what we’re trying to achieve. They didn’t have that. This is guys working in a shop that you quit when it’s dark because you don’t want to waste money on candles and lamps. And so oftentimes in certain areas, they would have restrictions on when you could work so that you weren’t putting lights in your shop so you could work more than anybody else and have an advantage. They had no ability to tell temperature other than looking at the colours of things. They had no ability to tell time other than maybe ditties or a sense of, OK, it should take as long as this happens to do this. And quenching, they are striving to imbue attributes into the material with the quenches they use, which they have like a recipe book for, in some cases. That’s one of the cool things about M.S.3227a, a part right before the fighting stuff that everybody talks about is a recipe book for how to soften and harden metal.

GW: Does it work?

CJ: Oh yeah, if you’re a smith and you read it, I did a paper at Kalamazoo on this, where if you’re a smith and you read this, you go, yeah, I know what they’re doing.

GW: Could we get a copy of this for the show notes?

CJ: Yeah, actually a more updated version would be I did a couple of blog posts, actually four blog posts on medieval heat treat on our on our website.

GW: I’ll find those and I’ll link to them in the show notes.

CJ: Yeah. It opens up the medieval mind, if there was one thing I could give people that are trying to do these kinds of things, getting a sense of the medieval mind helps you to understand how these things are laid out and processing in their heads. It’ll change your perspective on how all of these things relate to you, if that makes sense. So they thought of heat treatment as, OK, I’m going to make this material and I’m going to dip it into a solution with this, this and this in it. And I’m putting those ingredients in because I want attributes from those things in the material. And they had a very good sense of this, like the very early words that the Norse used to describe blades, they’re not talking about them being hard or about shattering like glass or anything like that. They talk about them being tough and ropey and, having a tenacity and strength, which indicates that while they knew about flexing and all these things, they also appreciated a blade that wasn’t going to break on you. One of the best examples of that is one of the things from 3227a is they talk about taking a blood serum, where they let everything settle and they take the liquid off blood. You put it on a feather and when you’re tempering a blade, you run the feather down the edge of the blade when it’s hot and you’re listening for a particular sound. And the sound they describe is [makes ripping sound] They literally write that in there. So what they’ve done is they’ve taken a blood product and using a feather can have turned it into a temperature device.

GW: What would that actually do?

CJ: So that tells you that you’ve tempered that material to the right kind of hardness, that you can sharpen it, but it’ll be tough and hold an edge.

GW: Tell me you’ve tried that.

CJ: OK, when you quench something, when you initially are hardening the material, you quench it. Today, almost everybody does a full hard quench and then you temper it, you reheat it, but only up into a certain level that’s going to be somewhere between like 800 and 1200 degrees. You’re loosening some of the hardness in the material.

GW: Is this 1200 degrees Fahrenheit or centigrade?

CJ: Fahrenheit. Sorry, I don’t deal in centigrade too much. I’m just working on including grams and centimetres. So the quench hardens it and then the temper reheats it, but not as hot so that it loosens the stiffness that you’ve created with the quench. Now in the Middle Ages, they did mostly interrupt quenches or what they call slack quenches where you dip it, but you only dip it quickly and then you pull it back out after a certain couple of seconds at most. And the internal heat that’s still in the piece is what does the tempering to the hardened edges. So you’re going to have a variable hardness in any medieval sword. The through hardness that we get in modern swords, where they’re between 50 and 52 hardness on the Rockwell scale, that’s just not done in the Middle Ages. If your sword is like that, it’s not replicating a medieval sword. But that’s what everybody wants in modern ideals. The idea that 50 Rockwells is a good hardness for a medieval sword is fine today, but it’s probably too hard for your average medieval sword. Most of them are going to be down in the low 40s. And that’s an effect of our modern material sciences and all those things, and then a less than full understanding of medieval sword blade materials from a generation or two ago, especially. Nowadays, we have much more information on that. You know, people like Dr Williams, who have been publishing works on this for a while. And you got people like Fabris doing great research. And Peter [Johnsson], we start to understand these things. They start to understand these things in ways that allow us to appreciate their work even more, but realise that sometimes our modern pursuit of this kind of ideal perfectness is just something that isn’t there in the medieval ideal. Symmetry, you know, they would do symmetrical, but it wasn’t like their main objective. And so sometimes you will see a guard on an arm that’s a quarter inch longer on one side than the other, or you’ll see a style of decoration on one side of the sword and a different style and on the other side. And they were done at different times. Or you’ll see weapons that have a decided lean or lopsidedness to them. And some of that’s probably from use. Other times it’s like they didn’t get wrapped up in that. Or in the case of something like a lot of the discussions of Norse swords with the cocked panels, it’s probably a process of either intention that they decided, hey, this works a little better if it’s cocked or because of the materials, because those tangs are all going to be soft iron. If you use the sword that happens. Because iron is a really soft material, if there’s no carbon in it, you can’t work hard in iron. So, you know, with the minimal amount of material that’s in a tang, anybody could take their hands, grab the blade or the guard and the pommel and give it a little twist with their hands. You don’t need a hammer or you don’t need a armourer to do that. I would guess that a lot of them happen just from use, the torque in your hand moving that material, because you know how much force you can create with a three foot sword, right?

GW: Yeah, I had this discussion with Roland Warzecha, he was an earlier guest on this podcast. And I can’t remember whether that discussion happened during the podcast or in the discussion afterwards. But one way or the other, I’ve got him on tape actually talking about how his theory is that these pommels are deliberately turned to basically fit a right hand or left hand better. His theory is that it is deliberately done in the making process. But if it is something that would just happen naturally, the thing is it hasn’t been corrected. The pommels are still like that. So one would imagine it’s something like breaking in a shoe.

CJ: Yep, yep. Roland thinks there’s more deliberateness to it than I probably do, just because I know how soft iron is. The old muscle guys in the sideshows would bend the bars over their head and stuff. Those are iron bars. They’re not steel. Because an iron bar, you can bend it back straight for the next show. And it is softer than steel. But I really appreciate Roland’s approach to looking at these things and researching and sharing it because I’ve had like at least two epiphanal moments with Roland at different times. One of the best was that we were down at a Western Martial Arts Workshop and I was in the tent and I’d been talking to somebody earlier in the day about something. And there’s this thing I call the active rotational point on a sword, where because you are gripping a sword in variable ways during its use and because of the design of swords and how all the components that you put into it interact with themselves as an object, the spot the sword wants to rotate around itself in front of you in a fight changes and it moves up and down the blade.

GW: I’m actually teaching a class on that, in terms of its practical applications on Sunday evening. It will be couple of months ago by the time you are listening to this, but is just a coincidence that you mention it that I’m teaching about this.

CJ: Yeah. And it’s something that I had evolved thinking about swords over time, and I called it this active rotational point and I was explaining it to somebody in the tent when I was trying to sell them the sword. And then Roland comes running over, a couple hours later, he’s like, yes, yes! It’s one of those things where people accuse us of having cabals because suddenly somebody says something and somebody goes, oh, yeah, and you’re down a rabbit hole and you can just see people around you thinking, “Oh, my God, what are they talking about?” But the two people talking are completely in sync. It’s the same thing that happens with me and Peter when we sit down. We lose people pretty quick, in polite society anyway.

GW: This is not polite society, this is Guy’s podcast and everyone listening is mad about swords.

CJ: I love those moments, man. Oh, that makes it all worth it.

GW: Absolutely. So I imagine if these medieval swords are heat treated, but not heat treated all the way through the way modern swords are, and they are a lot softer, they are likely to take a lot more damage.

CJ: In certain areas, and it literally is the kind of thing where the few blades that have been mapped out for hardness over their expanse are averaging from a little bit harder than what I would suggest for a sword, too much less, to soft throughout the blade and areas. Sometimes usually the edges are harder. Sometimes the edges have been added to out of better material. And there’s a variety of different ways they would construct the blades to do that. So your edge retention at 50 Rockwell with a modern steel is probably a little bit better than you would see in a medieval blade, but not so much. We got a way to go before we have to worry about that difference in our understanding of how these things happened. But the ideas that creep into modern thought on this are of this material should last, be impervious to their use, in a sense. You see this lot with like wooden hafts for pole arms,

GW: They are like the refills in the pen. I’m a woodworker, and to me the parts are inherently exchangeable.

CJ: Right. And you have the difference between a sapling grown to be a haft in a cold environment in northern Europe in the Middle Ages, with very tight grain growth taken down and left as a circular grain structure through its length. And then being mounted on some kind of a spear or on a pole weapon. With modern wood you go for as tight a grain as you can. But all the grain’s going front to back, hopefully. And you do what you can to make it as durable as that piece was in the Middle Ages, but the one in the Middle Ages probably had a little more flex to it.

GW: It’s like making bows. On the back of a bow, the grain has to run from end to end unbroken, for best results. And so when I’m making a spear handle or a poleax handle or whatever, that’s basically what I’m trying to end up using, even when I’m using modern wood, I’m trying to get to just the contiguous grain from one end to the other.

CJ: Yeah, and that’s not easy. Go out and find yourself an inch and a half by inch and a half square piece of wood with straight grain that doesn’t go off one edge or the other.

GW: That’s the thing, a poleax does not have to be dead straight.

CJ: No, it doesn’t. But if you’re swinging it like a baseball bat with all the weight on the forward end and hitting a hard target that’s locked down, the physics of it are human beings can break just about anything with the physics being right.

GW: What I mean is, to me it’s more important that the grain of the wood fibres run from one end to the other, regardless of straightness. When I do hit it, it has that flex and not that ability to absorb shock. That’s the trick. So you must have seen some pretty horribly damaged swords in your time. What was the worst?

CJ: Oh, man. Oh, let’s see. Well, back in the day, most stage combat was done with rebated swords that were basically swords, but just rounded edges and we got one back once from a show as a rental. And we actually sawed a two by four in half with it. It looked like a saw when it came out of the box. I’ve gotten a Fechterspiel back for repair, that literally the guard had been bent in a real good U-shape backwards.

GW: OK, just put that in context. I have a Fechterspiel on the wall next to me right now that I bought from Arms and Armor in 2007, I think. And it’s been my go-to standard training blunt longsword ever since. I don’t know how many thousand times has been hit with stuff and I filed off a few burrs and I cleaned it less often than I should have, but it has stood up without any trouble whatsoever. It’s probably got another 15 years in it.

CJ: You know, the only way I can make a guard look like that, that I know of, is sticking it over the horn of the anvil and hit it with a three pound hammer.

GW: Maybe they rested it on a rock and accidentally drove over it with a truck.

CJ: Well, no, it was a U-shape back towards the pommel. I didn’t ask. You see, sometimes you just don’t want to know and but that was pretty bad. Lately, a lot of what I’ve been seeing is grip abuse, where the amount of blow is being taken on the grip in the last 10 – 15 years. Quite a bit.

GW: OK, that’s fine. I guess I’ve probably replaced the leather on my training Fechterspiel four times. Maybe you will get a sword come in and it goes between your hands, thank God, and stops on the handle and splits the leather. I can see that would happen, I guess. You have been in this game a really long time. So how has the taste of the sword buying public changed?

CJ: Oh, geez. Yeah, from when we first started, the few people that were working with steel, doing any kind of work on the historical methodologies, we started using rebated swords. And then over time, it shifted to wood for a while. There are always trends and particular attributes people are emphasising, so sometimes it’ll be everybody wants the CoG [centre of gravity] way back towards the guard. Back in the 90s, especially. Centre of gravity, where it balances, when it’s an object on its own, where the balance is moving around and stuff. So that particular time period, some people had the idea that the CoG should be right at the guard.

GW: That’s horrible!

CJ: But it’s really easy to pick up and move around.

GW: But it’s not, because you have to do all the work of moving it. I generally go on a long sword about four or five fingers. Maybe five fingers for more of a cutty/whacky thing and maybe three and a half / four for something which is more elegant. But you want that weight in the blade so that you only have to get the sword moving once and then you just keep adding to its momentum and it will just keep going forever.

CJ: And all the intentions of your actions are specifically generated into the blade through having that forward balance, and if somebody is thrusting at you with a sword that’s got the CoG right at the guard, it’s pretty easy to just displace the point completely.

GW: There’s no heft behind it.

CJ: The other thing, well, in the last five or six years is super wide blades for cutting. The big eighteens. That’s suddenly become the thing to have.

GW: By “Eighteens” you mean sword type XVIII? I will put the sword typology stuff in the show notes.

CJ: XVIIIs have always been popular, but the big wide ones have as cutting has become a competitive thing at tournaments and such. A type XIII, it’s still tough to sell those except to a couple people that really like early swords, XVs come and go even though they’re one of my favourite fighting swords. The long tapering black prince kind of blade that we do. It’s a Fiore. It’s his sword. And then type XXs, there’s a couple of people that like them because a lot of times people are more focussed on what a sword looks like in their mind than what was used in the period they’re trying to replicate or the style they’re trying to use. And so you get people who want this kind of sword but they want it to look like that. Well, that didn’t happen, but we can try and do that for you, but it just makes it harder to make a good sword. And then you have things on a sword today because we know much more about adding the little things that they did that are there as aids or indicators for you as a fighter. Earlier I talked about one of my two favourite swords – the second one is the Swiss Sabre in the Wallace Collection. I made a reproduction of that and doing the reproduction and looking and studying that original taught me more about longsword in ways that I didn’t even understand until I was done with it, than just about anything. Because that thing’s a Lamborghini. It’s designed to be a longsword on steroids, because you have all these attributes on there that are specifically giving you tactile responses if you’re holding a weapon, in ways that you don’t even think about what you’re doing. So let’s see, I want to explain this clearly because it’s really interesting. That particular sword has a slightly curved blade. So when you do a turn, you have a leverage. If our blades are Indes and I rotate my hands slightly, suddenly I’ve got more leverage than you do because of that curve. The back edge of that sword has a has a greater area up where the sharp end point is and then steps down and has a long area that’s lower and then steps back up before it gets to the hilt. Well, those are tactile indicators for am I in the Vor, Indes, or in the Nacht? So when I’ve got you on the back edge of that sword, the instant your sword hits that lower point on the sword, I know that I’m stronger than you no matter what I do. But you don’t have to go, “Am I in the strong point?” You’ve got the sword going and telling you. It’s got a thumb ring. So the whole sword you can wind in all directions with two fingers and your thumb at most. So when I go to wind that sword, it really doesn’t matter how hard of a grip I have on it, because I can rotate it around fast with the time of the fingers, in a sense, at the time of the hand or time of the arm or anything else. And because of that rotational point on the thumb, well, you’ve used sabres with thumb rings, right?

GW: Yes. I’ve even used Swiss sabres with thumb rings before.

CJ: Yeah, yeah. If the thumb ring is placed right, you can just kind of let go of the whole sword and just use your curled thumb to control what’s going on. And so you’ve got the sword telling you, when you’re in those positions, the sword’s moving with the actions of just a few fingers of your hand, the grip is designed so that super thin secondary grip up above the midpoint there, in my ideas, those grips get super thin because you’re not to hinder the pommel when you are rotating or winding the sword. It’s so that the sword can wind inside your back hand without any resistance because you don’t really need that back hand on the sword until you’re making contact or until you’re using the leverage of the sword against the other sword. So you can kind of just let the back hand just sit back there and fly around it, not really grip it at all until you need it. And then there’s a thumb or there’s a riser slightly back from the edge on that sword. And this is one of the swords that taught me this, where these risers that you see the ribs around in the midpoint usually, and then oftentimes at the fore point next to the guard on a grip and then at the pommel, sometimes there’ll be multiples on there in a decoration. But a lot of times you’ll see in these later longswords a riser that’s half to three quarters of an inch back from the guard. And it kind of bulges out. Well, if you place the tip of your thumb against that riser and have it using as a kind of tactile indicator of where the sword is, but you can also use it in the wind to power the sword off your thumb. And if you’re not hindering that back end then that riser allows you a much quicker wind and turn of the sword than having your thumb up on the blade like a lot of the guys do. I think it’s a later development where they’ve said, well, if we let the thumb come back on the grip a little bit and have this riser there, we get the same result, with less effort.

GW: Wow, that’s interesting.

CJ: So you get all those components in this one sword. And it flies, it moves wonderfully in the hand.

GW: You’ve handled it?

CJ: Oh, yeah, and another thing is it’s got all these guard arms that come down, so it looks like you could throw your finger over it. But when you actually have it in your hand, really you can’t. Those guards go down and create that thing, so you’ve got a good, solid base for that thumb ring and those arms there are supporting other elements of the guard. And then it’s also got the knuckle bow that comes back and things like that. So I just think that sword is just like somebody who really knew, who was probably more of the Liechtenauer tradition of how to fight, and said let’s make the sword that has got all the things that you need to make this exceptional.

GW: Yeah, now obviously I’m going to have to get pictures of this to put in the show notes so people can see the riser and the little bit on just behind the back edge, just at the end of the back edge where it stops being sharp. That little kind of square nub you are talking about. So I will definitely be getting photos and putting them in the show notes. And you’ve reproduced this sword, right?

CJ: Yeah, we’ve made it a couple of times and we actually would love to make it as a regular product. We’ve been kind of working on that for a long time. But it’s something that we hope to do someday.

GW: Because I’m guessing it would be very expensive.

CJ: Yeah. There’s a lot of things getting all the components together. The blade’s got a lot of dimensional dynamics, that kind of thing. So it it’s not an easy sword to make, but man, you know, and the thing bit me good too when I was making it and I still love it. It was one of those ones where I was wiping the blade off and it sliced into my thumb and I didn’t even feel it. So I only noticed it when I went to lift my hand and the sword came with it because it was so embedded in my thumb.

GW: Woah! Ouch! You want a sword with a bit of bite to it and character. Treat it with respect or it will eat you.

CJ: Yeah. That’s another thing that’s changed a lot since the early days, is there’s a variety of sharpness. What people are after for sharpness, is something that changes relatively regularly,

GW: I imagine for tatami cutting, you want it just as sharp as it can be got.

CJ: Oh yeah, if you’re trying to slice something.

GW: I use sharp swords for basically three things, either for solo drills for cutting targets like the tatami or whatever, and for pair drills, sharp against sharp. And I have three different swords for three different jobs because the cutter is a gorgeous Damascus plated thing that JT Pälikkö made me. Oh my Lord, that thing is a lightsaber. The other one I’ve got, it’s actually, oh my God, I’m so sorry Craig, it is an Albion Sword, which is my usual solo drill sword. Because basically what happened was one of my students had it and they didn’t need it anymore. And so we did a trade about it and I ended up with it. It is a lovely sword. Nothing against Albion. These days, my go to for sharp-on-sharp training is these machetes. If you buy like a dozen of them, you can get them for about four dollars each. Totally disposable. You can sharpen them up a bit, regrind them a bit, whatever you want, and then you can do sharp on sharp drills and it costs nothing and they wear out really quickly. But you’re saying you think people’s desire for sharpness is changing over time. So why is that?

CJ: Well, you have people that are going to do to tatami cutting, you know, when people order swords they ask for it extra sharp, and I say, “Like tatami cutting?” And they say yes. We call that “snicky snack” in the shop. If they want a sharp sword, like a medieval sword, I’m not going to take it that sharp because when you look at the originals, they really do not seem to have those kind of tatami-esque edges. They come sharp, they’ll slice you. But in a lot of ways, especially a longsword is going to use thrusting and the impact of the cut as part of its interaction with you, so especially in the mid and in the back of the blade, you’re going to have probably a little more beef in that edge to take some of the interaction with other swords a little better than the tatami-type edge.

GW: Are we are we talking mostly about edge geometry or the level of polish?

CJ: Some of it’s going to be edge geometry and some of it’s going to be that last bit of honing. When you take two sharps against each other and you interact in that three dimensional space of a fight, it does affect an understanding of how these things hang to each other and bite each other, in a sense, and something where you come in and you’re displacing a blade and if you’re with your trainer, it just slides, or you’ve got to really work at controlling staying small with your action to control the blade and stuff. With a sharp you’ll suddenly feel like, OK, I’ve got him. I can feel my ability to control it a little better.

GW: The bind with sharp swords is a bind. The bind with blunt swords isn’t.

CJ: Yeah, and what I feel and what I found is when I take a real snicky snack sword and what I call a medieval edge or sharp sword, that sharp sword will bite the snicky snack more so. In essence, the tatami sword is going to get a little more damage to it. But it also is maybe has a little less ability to influence the other sword. And then suddenly you get down to minuteness of what angles are they coming together and are you binding in the bind and all that kind of stuff that most of us are probably never going to be at a level of understanding and touch in the swordfight that it makes any difference to us. But that’s one of those things that is always going on in the world of this stuff where, as a sword maker, people come to me and they say, well, what’s the best sword? Right.

GW: What’s the best car? It depends. Are you taking six of your friends to the pub or are you trying to get from A to B really fast or are you trying to impress girls? It’s three different things.

CJ: Yeah, yeah. And I always look at them and I’m like, I’m a sword maker, I’m here to sell you a sword. But if I’m honest, I got to tell you, the best sword is the one that’s in your hand when you need it. And it is your mind that makes the difference, not the sword.

GW: Right, and some swords, I pick them up and put them straight down again and others I pick them up and they kind of just get stuck to my hand and want to come home with me and somebody else will have the reverse response to that. And they’re both perfectly excellent. It is really personal.

CJ: I always tell people, who would you rather face: the best sword fighter in the world with a stick or the worst sword fighter in the world with the best sword?

GW: Easy question. It’s no fun getting beaten to death.

CJ: No, it isn’t. Plus, if you beat the worst guy, then you get to keep his sword.

GW: Oh yeah. Now, this may be a little bit off topic, but I seem to remember you telling a story which I have recounted many times, and I just want to make sure I’m getting the details right. But there was a king who wanted some greaves made, and he wanted them heat treated and blued. And there’s this correspondence between the maker and the king’s agents, or secretary. And the maker is trying to explain that you can have the blueing or the tough heat treating but not both, because they destroy each other. Does that ring a bell with you?

CJ: Yeah, it does. I think it was a Hapsburg, one of the kings of Spain and his secretary is writing to a German armourer. If I remember correctly, maybe Nuremberg, but he’s saying, yes, the king does want the blueing and the gilding and the heat treat on the armour and the guy writes back saying, well, we can do the heat treat or we can do the blueing and the gilding, but you can’t make the armour hard and then fire it again to put on the gilding and the blueing and all that stuff. And the guy writes back saying, yes, he would like all three. And that’s where you just up the price and do it anyway, because you know the king isn’t going to be out there using it.

GW: So he would have the heat treating, but it would be destroyed by the blueing and the gilding. But it wouldn’t matter because if the armour fails catastrophically, the king is in no position to complain.

CJ: Exactly. So, yeah, the customer expectation is a good part of my job sometimes. Just how do you achieve what you would like to have, in the ramifications of we have to deal in real world physics. We have to deal in real world materials and we have to deal in a budget where you have princely ideals and a commoner’s budget.

GW: That it is definitely an issue. I used to work as a cabinet maker and I remember there were some clients who say this is my budget and I need this to happen and does that work? And there were others who are like, well, I’d like to do this and this and this and this and this and this. And what you’re looking at is weeks and weeks and weeks of work. And then when you explain how much that’s going to cost, they look at you like you’ve just grown an extra head. They have no idea what they’re actually asking for. So, is there anything you wish that most historical martial arts practitioners understood about sword making?

CJ: Oh man. Yeah,

GW: Here’s your chance. Tell them!

CJ: Really try to understand the arts as they are depicted in your training from the historical descriptions. There is a huge amount of human existence that went into developing and practising and in a sense trying to perfect those arts in their time when they were used, when these guys were aware of all the negatives and positives of what they had. And today, sometimes we get into this modern mindset of, “I want it to be perfect,” or the tool becomes the focus as opposed to the art. As a sword maker, I want to sell you swords. But at the same time, a sword doesn’t make you a good sword fighter. And so understanding that if they did things in a certain way, that’s probably the best way at that time you could figure it out. Today, I see people really struggling with changing the items from the historical model to be part and parcel with other choices they’ve made like safety, and I’m not advocating not being safe with something, but if your gauntlets are so large that you have to extend your grip a couple of inches to make the sword usable in the art you’re using, then you’re altering it, and so don’t get hung up on doing it that way with this product, because you’re trying to put a square peg in a round hole. We had a blog post about this, about gauntlet size and stuff. And so we got an original gauntlet made out of metal laying next to a modern protective.

GW: The steel ones are half the size. With the steel one you look at it and think, my fingers are fatter than that.

CJ: Yeah. But it’s just there to protect you when you haven’t done the art correctly. That’s one of the things a lot of people doing armour fighting don’t realise. The armour is not designed to make you impervious. But it is designed for when your defensive actions in the fight have not been successful. And so armour was never designed to be like, OK, I’m going to load up and be a tank and just power through people. That’s kind of a modern idea of armoured combat, whereas in the period and in the style and construction of the original armour, we can see it’s light. It’s designed to be there, that if you get a hand hit, this will protect you. But it’s not designed to be able to take somebody pounding on your hand with a poleax for a week. So that’s a distinctly different objective, if that makes sense.

GW: Yeah. It’s a lot to think about. So there are a couple of questions that I normally conclude these interviews with I’m going to change them a little but because it’s you. You spent the last very long time making swords and building a business and basically I get the feeling that the business exists to enable the sword making.

CJ: Yeah, I mean, it beats having a real job as long as the cheques don’t bounce.

GW: So the best idea you’ve had that you acted on, probably was getting into sword making, but what is the best idea you’ve not acted on?

CJ: You know, I think one of the things that I always really thought would be a valuable thing for the study of all things medieval, would be some kind of a collection or a focus. Well, Dr. Keith Alderson, you remember Keith? Germanicist. I just had several epiphanal moments with the guy over the years. But when we were coming back from a Western Martial Arts workshop once we thought, you know, if we can find one of these small college campus closing up and turn it into kind of a research scholar centre for craft and research and language and history of the Middle Ages, where you get the interaction of all the disciplines and you get people that are creating research and studying not only how swords were made and the materials used, but also the how the pieces were used and how the brewing was done and how butchering was done and how a lot of those components could come together, because when you look at the recipes for the swords, well, they’re talking about using buck’s blood when it’s in heat. So somebody’s got to go out and get a buck when they’re in heat and those kind of things and see what all of that stuff. When we do have descriptions from the past, they’re telling us what it was and they’re not doing a huge amount of “There’s a super secret thing that we’re not going to tell you.” But they do describe it in ways that the medieval mind has understood that maybe we don’t because we’re so affected by this idea of, well, we know all this stuff.

GW: Also we have different frames of reference. OK, so usually my next question is, somebody gives you an ungodly sum of money to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide, I’m guessing you would spend it on that centre that we just talked about.

CJ: Oh, yeah. If it was an ungodly amount because that would take a million billion bucks. But, you know, even if I had a reasonable amount of money, what I would probably do with a reasonable amount of money, I would probably try and fund research into the legal records of the guilds and the merchants that we have surviving. We keep we keep finding these titbits, these things that enlighten us about how and what they were doing with their industry and their ideas from legal records, people suing people, people killing people. You know, I think there’s probably a vast amount of information that would be pertinent to our understanding of combat and how armour and weapons were produced and made and used and documented and all those things that we just don’t get because nobody’s trawling through 1560 Nuremberg, who sued who.

GW: So in this centre of yours there would actually be a legal scholar as well. That’s fascinating. Everyone else I question has such a good ideas, I always end up saying, you know, if I had the money I would give it to you, but sadly, I spent the last 20 years swinging swords around rather than founding PayPal.

CJ: We’re all just waiting for that one sword student to win the lottery, right?

GW: Yeah. I think that’s a wonderful note to finish on Craig. Thank you very much indeed for talking to me today.

CJ: Oh, thanks for having me. We should do this more often, with pints.

GW: Thanks for listening, I hope you enjoyed my conversation today with Craig Johnson. Remember to go along to a www.guywindsor.net/podcast for the episode show notes, which include transcriptions and, of course, a picture of the Swiss sabre that he mentions. I should also mention that the transcriptions particularly are there, courtesy of my wonderful patrons on www.patreon.com/theswordguy and as ever, a grateful shout out and thanks to both new patrons and existing ones. My patrons are apparently a fairly shy bunch and they tend to prefer not to be credited by name. But I see you and I see what you do. So thank you very much for your support. Let me also please remind you that if you could go along to www.patreon.com/michaelchidester and support the incredible Wiktenauer project, that would be extremely helpful.

Tune in next week when I’ll be talking to Beth Hammer, who is an artist and an extraordinary artist at that, I have seen much of her work and it is a delight. Well, some of it is a delight and some of it is rather challenging. And that’s what good art is supposed to be like. So the reason she’s on the show is because not only is she an artist, she’s also a fairly high level armoured combatant in the Battle of the Nations scene. To be honest, I don’t know a great deal about Battle of the Nations, which is one of the reasons why I have got Beth onto the show to tell us about it. And we have a fascinating conversation, which includes things like throwing people through fences. If that sounds like your sort of thing, make sure you tune in next week. So to make sure you don’t miss that, please subscribe to this show wherever you get your podcasts from. And while you’re there, if you wouldn’t mind rating it or reviewing it, that would be marvellous. It really helps to spread the word. So thanks for listening and I will see you next week.