GW: I’m here today with an old friend of mine from the Dawn Duellists Society days, Dr. Milo Thurston, who is the founder of the Linacre School of Defence and an absolute bastard with a single stick. Milo, welcome to the show.

MT: Thanks. It’s great to be here.

GW: I should perhaps explain the “bastard with a single stick” thing. The last time we fenced single stick was in Sweden at one of the early Swordfishes.

MT: oh yes, I remember that.

GW: And I went home stripey. I took my shirt off to show my girlfriend at the time, and she was like, what the hell are you doing? I said, I got Milo’d.

MT: Yes, you did leave me with a nice stripe across the inner thigh.

GW: Well, that is just what friends do.

MT: A very good one indeed. Nice to show off for days afterwards, not that it was easy to do so given where it was placed.

GW: Indeed, OK, so just to orient everyone listening, where abouts in the world are you?

MT: I’m currently near Oxford, Chipping Norton, so shorthand on Twitter for toffs and I suppose one might have called Sloanes but is not like that at all in reality. Though, ok, one can bump into David Cameron and the likes around here.

GW: Oh God, I’m so sorry.

MT: I encountered Clarkson when I was trying to buy milk at Sainsbury’s once.

GW: Oh no. And did you have a single stick available to administer the necessary thrashing?

MT: Unfortunately not, no. And I think they disapprove of that in Sainsbury’s anyway.

GW: Yeah, you might get barred from the supermarket for chastising Clarkson. Okay. And you’re near Oxford because you’re at Oxford University, is that right?

MT: That’s right. I’m still working there. I’m writing software for scientific research.

GW: I thought you were doing electron microscope stuff?

MT: That was up in Edinburgh. I was doing electron microscopy there. Then I went to Oxford to do the DPhil, which was on virus transmission and pathogenesis.

GW: Really?

MT: Yes. Not human viruses though. And I’m a bit out of the loop when it comes to viruses, the ones I looked at spread by aphids anyway and I haven’t been on the bench for years, then I ended up going to do climate modelling after that.

GW: OK, and are we all doomed?

MT: Well, bit of a complex answer to that one, but I will say, though, that I was just the chap that made the computers work for them, not a climate scientist.

GW: OK, fair enough.

MT: I did occasionally get dispatched by the professor in charge to give talks to the public. But I think the way he liked it to work is if it was a big thing with The Guardian hosting it and he’d be in the papers and on the news, he’d do it. If it was a scientific conference, but it wouldn’t get him in the papers, he’d send one of his PhD students or one of his postdocs or something. And if it was public outreach where it wouldn’t get him in the papers and it wasn’t a scientific audience, but they wished to see how our project worked and have lots of exciting slides and some waffle and he’d dispatch me to do it.

GW: OK, so. You moved to Oxford in 1999, is that right, and started the Linacre School of Defence then?

MT: I think 98 to start the DPhil, and it took a year to get everything sorted and recruit enough people interested in doing a bit of historical fencing.

GW: OK, but how did you get into martial arts?

MT: Via sport fencing. Because sport fencing, at least I perceived it a very long time ago as actually a proper art, proper sword fighting, in a sense. I think it still is. The principles of the art are certainly true. But what I didn’t know at the time is something I saw years later, I think it’s on a website called www.nononsenseselfdefense.com, an article about five focuses of martial arts, which I found very enlightening. I can waffle about it briefly.

GW: Yeah, please go ahead.

MT: Certainly. What it says is that certainly any one art, be it fencing, karate or whatever, it can be practised with different focuses. And one focus will equip you very well for that particular thing. But it may equip you very, very poorly for something else. And sport fencing has got a particular focus that is not the same as the sort of HEMA I want to do. And therefore, as I was trying to do sport fencing with the wrong focus. It kept annoying me in various ways. I kept looking for something else to do. It wasn’t SCA, a different thing altogether. Certainly not re-enactment, dreadful sword fighting that goes on there, for various reasons, because of the requirements of what they’re trying to do.

GW: Yeah, it’s a different thing,

MT: Different constraints that just don’t see what I was after. What those focuses were briefly, firstly, combative. Secondly, cultural and self-improvement, enrichment. Third, sport. Fourth, fitness and fifth, stage, fight choreography.

GW: I put something like that in my Swordsman’s Companion. Five poles for a martial art, where it’s either designed for actually killing people or it’s designed for winning tournaments, or it’s designed for personal growth or it’s designed for longevity or health and what have you, or it is designed for spectacle like putting on a show. Hmm. Maybe they got there first or maybe they cribbed it off me. I don’t know.

MT: That I don’t know, I can’t recall when the two were published.

GW: I shall have to look into it because I might have absorbed it by cultural osmosis and then rabidly plagiarised it in my book. That wouldn’t be too surprising.

MT: It is a sensible idea and there’s nothing to say you both didn’t come up with it independently.

GW: Yeah, possibly. You’re right. I mean, sport fencing is a highly evolved system for taking a theory and practise of fencing and making it work in tournaments. And that’s what it’s for. If you win an Olympic gold medal, absolutely nobody can say you did it wrong.

MT: Well, quite. I would say, though, of course within that context, absolutely not. But if that same Olympic gold medallist tried that with an actual sharp sabre, they would find it probably was wrong and they would get impaled quite quickly.

GW: Most likely.

MT: But under their rules it’s great and they’re extremely athletic. Extremely skilled.

GW: OK, so you were frustrated with sport fencing and then what happened?

MT: Well, I’ve looked around for various other things. One thing I did find a bit of in St Andrews when I was at Dundee, I could go to St Andrews for this and also in Edinburgh later, just before the DDS was a bit of a single stick going on. Professor Bracewell.

GW: Bert was a great man.

MT: Yeah, this was great stuff. And I used to go to the Sport Fencing Club in Edinburgh specifically to get lessons from him at single stick.

GW: OK, and is that how you came across us, the DDS? Because we were getting single stick lessons from Bert as well.

MT: And he, after a bit, said, well, you might want to keep coming here, but if you’re really into this stuff, you ought to go and see these people and sent me towards the DDS.

GW: Fantastic.

MT: Earlier on I used to drive to St Andrews from Dundee to do single stick as well. But Bert wasn’t there, it was someone called Derek Titheridge.

GW: OK, so I remember you showing up to the DDS and at some point maybe we had been training for a while or not, but you had these single sticks that were like an inch thick ash cudgel. Do you not remember these? Everyone else is using rattan or like slim, maybe half inch, three quarter inch ash sticks, and you come down with these hoofing great logs of firewood and no one would fence with them except me because they were worried about getting their bones broken. You don’t recall it? Oh my God, it’s one of my endearing memories of you. I’ll fence you, and the thing is there was nothing to be afraid of because you weren’t actually going to break anybody’s bones with it. They were quite big and heavy. But you were careful with them. And, you know, we had some great fencing and some good bruises, but nothing untoward occurred.

MT: Excellent. Well, it’s just as one gets older, memory is quite malleable. It’s hard to recall the detail. I remember at one point I had a batch of really, really rubbish ones that broke all the time.

GW: Maybe you replaced them with these cudgels of doom.

MT: It could be because I have got in mind that they kept snapping and I had loads these really thin ones that are absolute rubbish. Yes, that was probably it.

GW: OK, so you got into Sir William Hope somehow. Did we introduce you to Sir William Hope or was that something you found on your own?

MT: I think you had a copy of The Scots Fencing Master that I had a look at.

GW: Yeah, we had a photocopy of it from a private collection.

MT: I didn’t get a chance to read it all, but when I moved to Oxford, I spent my year when I was getting stuff ready, going to the Bodleian, and I was able to get hold of various other Hope’s works and read those. And so, yes, now this thing I did see up in Edinburgh, and it certainly was as good as I thought it looked.

GW: OK, so The Scots Fencing Master is pretty standard French smallsword stuff, and then The New Method is completely different. And there’s only like 10 years between them, 15 years between them, something like that.

MT: 20 years.

GW: So what do you think happened that made Hope come up with his new short and easy method of fencing?

MT: I’m not exactly certain, though, one thing I will note is the guard that everyone knows from his New Method was actually in The Scots Fencing Master.

GW: Oh, was it? I’d forgotten that.

MT: It is described there. Except at that point he lists the various guards in order of how good and useful he thinks they are generally. And he lists that one bottom of his list. And so it’s moved over 20 years up to the top. Now, in between, he wrote things like The Sword Man’s Vade Mecum, in 1691, if I remember correctly, which is just a book on if you’re caught out in the dark alley and get attacked by someone or you actually have to fight a duel with someone who’s really trying to kill you, what techniques you’d use. And very few is the answer. He gets it down to the absolute basics and even suggests not actually lunging.

GW: Right. Well, lunging is dangerous. You could fall over and if you look at smallsword lunges from Angelo, for instance, it is really short. You move the front foot its own length forward. There are some French fencing treatises which have long lunges in the 18th century, but Angelo, short and Hope, kind of short lunge. Though doesn’t he actually recommend in The Scots Fencing Master getting your thighs to 180 degrees so as you go left your back thigh can’t be pierced by your opponent’s sword?

MT: Almost, turning the back foot out as far as it will go. So you become very much edge on, a dreadfully uncomfortable position. Later on in the New Method, he just starts saying take such and such posture as much as possible without constraint. So all I can think is that over time he started to realise, well, actually I got taught a whole load of stuff early not all of it’s useful. I like this stuff. This is what’s worked for me over the years. And he just gradually refined it, which is, of course, what we’re supposed to be doing with HEMA interpretations anyway, is not remaining with one static interpretation, but constantly evaluating what we’re doing.

GW: Yeah, absolutely.

MT: He was, clearly, and it shows. In his next book, actually he changed it further.

GW: What was the next book? I don’t think I’ve read it.

MT: That was his A Vindication of the True Art of Self-Defence, I think three quarters of which is a waffling essay about the morality of self-defence. And the remaining bit is his Vade Mecum, A New Method, with knobs on and a few revisions. Where he essentially says don’t use that guard all the time. Use some other stuff, too.

GW: OK, well, we should probably just briefly summarise The New Method. There’s bound to be some people listening who are not intimately versed with Sir William Hope and we must bring light to their poor benighted lives. So would you like to explain for us what actually is Hope’s New Method and how it works?

MT: Certainly. A book written in 1797, his idea was that gentleman might have to use a small sword, a spadroon or a broad sword or a back sword or something. And he ought to understand both cutting and thrusting. And he describes, even if you’re training with a small sword, you should at least practise blows and at least understand all of that, not just train only thrusts or only cuts and he has therefore come up with a universal system that any one handed sword of a reasonable weight could be handled and used effectively for defensive purposes. Where it works really well is against opponents who are wildly thrusting and or the sort who, when they lunge their thrust, drop a bit and they stab you quite low in the guts. Actually, people who are aggressive forward who aren’t necessarily very good. It’s useful against those. If you try it against someone who is very good, say Angelo style, they start to spot the bits they can take advantage of. And so I don’t think it’s necessarily a perfect system for all small sword fencing, but it works very well if you have to pick up a sword in the 18th century and defend yourself against sharps.

GW: And how does one do that?

MT: Basically with a hanging guard in second. Imagine Silver’s true gardant and instead of the point back towards your knee, forward towards the opponent so you narrow space on sword or engage his point. And parry with prime and second very high.

GW: OK, you basically hold your sword hand above your head, your blade is hanging down, but pointing forwards and anything that comes towards you, you just move your hand over one side or the other to cross it.

MT: That’s it, yeah. To your left or to your right.

GW: Yeah. OK, so it’s basically like a totally simplified school. But we see it in more than 50 years later described as the German Guard in Angelo’s school of fencing. So do you think that the Germans took up Hope’s method or Hope might have been influenced by a German visitor, or convergent evolution?

MT: I don’t know. The only Germans who study the German system I’ve spoken to at the Smallsword Symposium get very upset when they’re told that hanging guard in second is German. They say absolutely it isn’t and German stuff is nothing like that.

GW: Now the listeners can’t see, but I am digging out a copy of The School of Fencing.

MT: Mine is two floors down, I’m afraid.

GW: Why, yes, I’m in my study, because I was going to basically check my reference, but I’m pretty sure of it. Yeah, so the defensive guard of the smallsword against the broadsword, the broadsword is in that kind of hanging guard position. There should be a picture of the sword and lantern. Very handy. Never go anywhere without your lantern and the Spanish guard. Very fine hat. I might have to edit some of this out if I don’t find it in the next two seconds, because it’s probably not the best audio entertainment ever produced. Oh, observation of the German guard. I don’t think he’s got a picture. Yeah, so “in the position of the German guard, the wrist is commonly turned in tierce.” I don’t see how the wrist can be turned in tierce, exactly, the way he’s describing it. But “the wrist and arm in line with the shoulder, the point of the adversary’s waist, the right tip, extremely reverse from the line, the body forward, the right knee bent and the left, exceedingly straight. The Germans seek the sword always in prime or second and often thrust in that position with a drawn in arm.” There you go. “They keep the left hand to the breast with an intent to parry with it.”

MT: It does sound fairly similar.

GW: It does, doesn’t it? Yeah, and that’s incidentally, Harry Angelo’s translation of his father’s book that was originally written in French. That’s the 1787 version. For the listeners, as I’m sure you’re familiar with it. OK, so, all right, I get the Hope thing. He was one of the first historical fencing masters that I really came across and got access to the material and I love Hope, but not so much that I forsook the earlier arts and I’m more of a rapier and longsword person. So what is it about Hope that made you want to basically start a study group for Hope, the Linacre School of Defence?

MT: Yes, well, I simply liked what I read, his verbosity, that many people complain about never bothered me. It all made sense. His attitude seemed to be very much what I was thinking when I was getting annoyed with sport fencing, that he was thinking fencing should be about defence and treating the sword as sharp. And he critiqued a lot of things that I thought sport fencers did. In one of his books, probably the Vade Mecum, though apologies to anyone listening if you go look it up and find I’m wrong. But he makes some complaint that watching people fence one might almost think that the highest art they aspire to is to see who can contretemps the oftenest. By “contretemps” he means exchange with each other, thrust simultaneously. I read stuff like that and I thought, yes, finally, this chap is talking sense about fencing. This is what I want to read. And he produced a lot of material. It’s good material. And I thought, well, I’d rather stick with that rather than try to spread myself too thin.

GW: OK, so you’re doing like a smallsword and backsword, mostly, is that correct?

MT: Yes, and a bit of spadroon. And we finally found something that’s an adequate training for.

GW: OK, and. All right, so I’ve always been fond of a spadroon, it’s kind of like a cross between a smallsword and a sabre. So what is the difference between using a spadroon and using a backsword?

MT: Well, what we find is that we’re using the exactly same system with each. But the spadroon, it’s a lot quicker because it is lighter. It’s easier to handle for certain cuts. If you entered a massive cleaving shot at someone’s head and tried to split their skull, the backsword does the trick. But sniping shots at the wrist or the face quite quickly, particularly the time cuts or ripostes and the like, the spadroon does that a lot better. It thrusts better than the backsword and cuts better than the smallsword and is halfway between the two. Hope really liked them from what he seems to have expressed in The New Method, I think he would have thought it the best sword to carry if you didn’t know what to expect.

GW: Fair enough. OK, so when was a spadroon normally carried, historically?

MT: Well one person who carried them was actually centre company officers of the Napoleonic British Army. I think seventeen ninety six or seven patterned sword is a spadroon. Royal Naval officers.

GW: OK. All right, we are definitely going to get onto the Napoleonic living history thing so we can go into depth and detail about who exactly that officer is and what they would have been doing. OK, now, I’ve obviously I do a little bit of research for these interviews and I came across an interesting thing on your website. So I’m going to ask you, what is the Christmas prize?

MT: Yes. Another thing from The New Method is there’s a long and waffling section, that goes without saying for that book, really about how every master running a school and he uses master in the sense of schoolmaster or person in charge of the school, not necessarily expert. He assumes actually that the master may not actually be that good, but they’re still a master because they’re running a school. They should organise once per year a prize or a tournament for all their students to take part in. And I think he has it where they all put some money into a pot and they all fight by elimination and one or two bouts per day over a period of a week or so until eventually someone wins and takes the prize. So, ah, well, this might be an entertaining thing to do. So the last session before we close for Christmas, I would run this and there would always be some amazing prizes that would be supplied. Students would have stuff, for example, back in the old days when we were actually in Linacre College, a bottle of Linacre sherry for the winner, and for the runner up, two bottles.

GW: So they can console themselves in their defeat?

MT: No, because it’s really nasty.

GW: Oh, right.

MT: Bad stuff, indeed.

GW: OK, and how do you run your tournaments? A lot of the listeners fence in longsword tournaments or have some interest in the whole tournament structure of things. So how do you run your tournaments in your school? What do they look like?

MT: In this case it would usually be done as a pool with a sport fencing style pool sheet. We’d rarely have more than eight people and everyone would fence everyone else. The rules were changed every year on purpose. Whatever rules I thought were most interesting at the time, or some different variants on hits against you or for you, or if you stab someone, you get the advantage. If you stab them again whilst you have the advantage, you win. This sort of stuff or different points for different target areas or whatever else. Virtually every variant we’ve tried something. The idea of this was just to attempt to eliminate the sporting aspect.

GW: The gamesmanship.

MT: Yeah, some people though would do that anyway. The moment I explain the rules their thought would immediately go to, all right, how can I game this?

GW: Yeah. Just human nature isn’t it.

MT: Indeed, we’d always get those occasionally. And sometimes if there was enough time and the right number of people, we would run two pools and do one with smallsword, which was compulsory and one with backsword if we had extra time. And sometimes the winners of each would fight each other with disparate weapons.

GW: Oh, excellent.

MT: It’s just a bit of variety, but it always included a smallsword pool every time.

GW: Right. OK, and did you notice was there a particular ruleset that produced good results or was it the constantly changing ruleset that was most helpful?

MT: Generally, people who were good fencers would tend to do well. The people who were aggressive boors, you obviously can’t avoid them in a fencing school, who would just go in to win, sometimes the rules would favour that. Sometimes they wouldn’t favour that. It depended on the individual, on the ruleset on the day. So it’s difficult to say whether any one set was particularly good, but I don’t think really any of them probably was enormously better than any of the others.

GW: OK, yes, sort of what I would expect, because as soon as you have a fixed ruleset, the gamesmanship comes in and you get all sorts of unintended consequences.

MT: Definitely.

GW: OK, so. I would be remiss not to also ask you whether you still have the Tawdry Tartan Talisman of Tardiness and have I remembered that correctly?

MT: Indeed, yes. It’s somewhere probably in a bag locked in the university club in Oxford, which has been turned into a covid testing centre or something like that. And we’re not allowed to use it. So in fact, training elsewhere, but not this week because the parish council have bagged the hall for public meeting.

GW: You just have to buy yourself a salle.

MT: If I win the lottery. Yes, but it’s in there in a bag. What it was is a little shield made of tartan with a T on it. And it had tartan ribbons and bells that a member of the school made many years ago. As I hate lateness and they thought it was this hilarious joke to make me this thing and say I should force whoever turned up last to a session, if they turned up after the class started to wear it and we actually used to do that. And whoever came in after the warm up had started would have to strap this on and wear it with bells tinkling for the entire time.

GW: Then does it have a salutary result in terms of timekeeping or was it just fun?

MT: No.

GW: So it is not sufficiently awful. Well, what I used to do, because I’m punctilious about time and I routinely leave vastly early if I have to catch a train or a plane or anything. Once in 20 years of teaching historical fencing professionally. Once I started a seminar three minutes late, and it still burns me 15 years later. I was driving to teach a seminar. I left plenty of time, but all sorts of things happened on the drive, got stuck behind a tractor, that kind of thing. And I got there literally at the starting time and I had to get changed and get in the hall. And so I got one of my students to start the seminar and start the warm up. And I came in three minutes late and I nearly died. No. I can’t bear it. But what I did in my salle, was the clock on the wall was set five minutes fast and class always started 6:00 p.m. on the dot of salle clock. So, if you’re trying to cut it super fine and just like get there 2 minutes before class starts, you’re always going to be late. When I mentioned it to somebody I know in a Facebook post, ages ago, I don’t really do Facebook anymore. There’s one student who’d been training with me for like 10 years at that point, and she was like, oh, my God, that explains it. My five minute fast clock. As soon as I left Finland, they set it to the regular time. I don’t approve of that at all.

MT: I never went as far as that clock, but it was always the moment it gets to the hour on my watch and we were starting in the warm up would start. Sometimes I’d lock the door. So any slackers had to pound on it for entrance and then be told to do press ups in front of the class whilst everyone else ran on the spot or something like that. It sounds like some sort of sad power trip, but it was never meant to beast anyone. It was just meant to say, look, you shouldn’t be late. And here is a mild forfeit to remind you.

GW: What we would do is if you miss the opening salute, you are late and you have to do ten push ups or if you’ve got an arm injury you can do squats or something instead, and then you can join the class. But if you’ve missed the warm up, you’ve missed the class. And you’re welcome to sit and watch and maybe take part in free training and stuff afterwards with the class itself just has that warm up grace period. Punctuality, I know some people’s brains just don’t do it, and in some cultures it’s a lot more flexible than elsewhere. But to my mind, and particularly finishing a class on time it’s really important because people might have someone they need to be. And it’s rude to leave the class early or it could feel rude to leave the class early. So you have to finish the class exactly on time so everyone knows where they are. They can go catch a bus if they want. I even do this with my online seminars. My Coach’s Corner thing, it starts at three, finishes at four. And so at four o’clock, I thank everyone for coming and say I’m going to stick around and chat for a while. And normally we carry on for another half an hour. But anyone who needs to leave at four can do so without feeling like they’re rude.

MT: Sounds good. I certainly approve of all the attention paid to punctuality, I think it’s essential.

GW: Do you know Ken Monschein?

MT: Indeed.

GW: OK, his PhD, have you read it?

MT: I haven’t actually had a chance.

GW: OK, yeah, it’s really good. I emailed him years and years ago and he sent me a copy of it. And his PhD is all about timekeeping in medieval Paris. And how they use the bells of the different churches to tell people when they have to start working, when they could end work, and basically the whole culture of bell ringing in Paris, if I remember rightly, he put it something like, and so all of these bell towers and everything were basically just so that the faculty members of the university could get to their meetings on time or something like that. I mean, it is classic. I actually think of the many, many, many people I know, I think you’re one of the very, very few that actually enjoy reading that PhD. I loved it. But it’s like most PhDs, it’s like nobody’s ever going to read it.

MT: Well, probably more likely to than mine, but still, I ought to go and have a look at it. Whilst we are discussing lateness, it just reminds me of the chap it took me in Dundee in the sport fencing class that he taught there. He didn’t like lateness either. If people came into his class late, he would shout very loudly, some quite foul stuff that I can’t really repeat on a family podcast about what he thought of them and their attitude and what they might do with it.

GW: Yeah, I’m not a fan of that because it’s like, OK, people have reasons for being late and it’s better that they show up late than they don’t show up at all, generally. That’s actually one of the very, very few advantages of teaching an online seminar rather than in person is I start my classes on time and there’s even a clock built in, the computer has a clock on it. So I know exactly when to start. And I disable the waiting room, so that if people are late they can just show up and because they’re muted, they’re not interrupting anything, it’s just like an icon like flickers open on the screen and that’s that. So if they can’t get there on time, they can show up without feeling like they’re interrupting everybody.

MT: Something much, much better than walking into a lecture late. Disruptive.

GW: Indeed. Yeah, I think the average listener of the show probably was not expecting a lengthy disquisition on tardiness today. But OK, so let’s get a little closer back to topic. OK, so you do Napoleonic living history. So 18th century is sort of your area, right?

MT: Yes.

GW: What is it like, what you learn from it? How does it add anything to your historical martial arts, if indeed it does?

MT: It does actually. The interesting thing about that is what I’ve mostly been doing over the past 20 years is, well, Napoleonic infantry and I have ended up as an officer of infantry. And so it is actually a martial art as such, except my weapon is 30 or 40 men.

GW: A martial of war.

MT: Exactly. So I accept I’m trying to fight with them. And rather than thinking, well, if I swing my sword this way, can he parry it? Where will he riposte if he does parry it, is he in range to hit me? How much distance must I cross to hit him? I’m thinking the same things, but I’m thinking them in very slow motion. How many rounds must I fire? It’s going to take me 20 seconds to reload each one. I’m going to wheel my unit round here and cross that terrain. And what if that cavalry comes over here? And will he bayonet attack me from this side and advance this way and still having to think of all that stuff, much as I’d be thinking in a sword fight. But over that, longer periods of time, several minutes and longer distances.

GW: OK, I know you’re a musician. It just occurred to me that it’s like a trombonist plays a trombone, and a cellist plays the cello and a conductor plays an orchestra. So they make the orchestra, they basically play the orchestra the way a trombonist plays the trombone, they want a bit more of the sound over there. They want a bit less of this sound over there. They want to up the tempo or whatever. So the relationship is, I guess, similar to an infantry officer to a fencer. It’s like a conductor to a musician.

MT: Indeed. That seems like a reasonable analogy. As for the individual soldiers that they’re not actually doing anything that we would perhaps recognise as the sort of HEMA training we do. They are methodically going through movement by movement the operation of their musket and firing in particular ways on command, almost mechanically. So the actual fighting is being done by me, by giving them orders.

GW: So are you recreating known battles, or are you actually sparring?

MT: It varies. Sometimes it is known, for example, I was at the 200th anniversary of Waterloo.

GW: That must have been great.

MT: It was. I got to command the Defence of Hougoumont, and the Ministry of Defence actually sent us some real guardsmen so they could say the real troops were there. Not many of them. So we had actual real ones in there, one of whom, the French were naughty and they fixed bayonets when they were told not to, one of whom got a scratch up his face from a French bayonet and then apparently bragged about it in his barracks afterwards that he got this off the frogs at Waterloo.

GW: So that would have been following the pattern of the battle as it was actually fought.

MT: But if I may go back to that, please, the rest of it, if we’re just coming up with scenarios, essentially, then the stage combat aspect is we have a discussion beforehand that what the scenario is, who’s expected to win and roughly what order. And then we go on to the field and we attempt to represent this with communication as best we can and thinking about how it might look with our opposite numbers so that I might attack them. But this is the start of the battle and we know they’re not going to be beaten immediately. So I’ll take some hits and I’ll withdraw my unit and another unit will come up as I’ve withdrawn and carry on the fight and we try to make it look appropriate to the public.

GW: OK. And do you ever do it without the public, and without staging it beforehand?

MT: Yes, just for our own training, we will organise specific training weekends to do nothing but drill and manoeuvring, get everyone trained up appropriately.

GW: Obviously in fencing you get hit. But when you’re shooting black powder muskets at each other, no one should be getting hit at all or someone is going to die. So how do you who’s being hit?

MT: We have to guess, based on our experience of actually firing the muskets with ball in which we’ve done on occasion, usually in the Napoleonic unit I’m in, we would organise once a year since I’ve been the secretary of a Rifle Club, we organise a session where we actually fire those muskets at various distances and see how good they are. So at least we have an idea of how far that ball will carry and how accurate it is. Yeah, if that many men launched a volley on us at that this distance, yeah, we would have taken some hits. Let’s call for people to fall down dead and let’s withdraw a bit.

GW: OK, so you basically make an educated guess as to how many people would have been shot and then tap on the shoulder and they have to fall down.

MT: That sort of thing.

GW: OK, yeah. I mean, some kind of laser tag would be possible.

MT: Potentially.

GW: That would be quite interesting. I mean, obviously, laser tag, you can shoot a thousand rounds a minute if you’ve got a very quick finger, so you need to have some way of limiting the rate of fire but that might give you an eye to some sort of… It might put marksmanship and like luck into it a bit.

MT: I suppose paintballs possibly as well, all manner of things. The difficulty then is it starts becoming more HEMA-like in the sense we’re starting to wear protective gear and use equipment.

GW: You wouldn’t do it for the public.

MT: Indeed for ourselves. It would be very interesting

GW: Because if I remember rightly, I think it’s in David Grossman’s On Killing. He talks about rates of fire in infantry units, how many people shoot their muskets at all, and how many people are actually aiming. And he refers to battles that have been recreated, Napoleonic era battles that were recreated by regular army units using laser technology and the death toll was 10 times what was in the original battle. Are you familiar with that work?

MT: No, but it doesn’t surprise me. From what one hears, certainly American civil war battles, from what I’ve read, the early ones, the troops were not very well trained.

GW: OK, that might be interesting to look into.

MT: It just reminded me of an anecdote as well, again, the stage aspect of it just occurred to me is that we did an event in Northern Ireland once. There’s a Museum of Irish Immigration to the US set up to look like an American village or town that settlers had arrived at and they wished to do the War of 1812. Bizarrely, some Germans turned up dressed as Native Americans. Very strange. And they just spoke German to represent the language. But we were supposed to attack this town, and so I had two platoons, I sent the first one in, they encountered the enemy, they stopped. They fired a volley, but they didn’t know that one of these Native Americans had hidden in the bushes right next to them. And the moment their guns were all empty, he jumped up and tomahawked someone in the front row. This isn’t the best bit. So he whacked this fellow with a tomahawk, he fell dead, and he sprinted off thinking he’d get away before they reloaded. But one chap’s gun had not sparked, so he cocked it, fired again. It went off. And this fellow who’d done the tomahawk knew exactly what had happened. And so he thought they must be shooting at me. And so he took a spectacular dive as he though had just been shot dead set and thought this was great. It must have been staged, but absolutely not, it was completely improvised.

GW: That’s fantastic. I’ve shot some black powder and there’s something just blissful about it. Particularly a musket where the pan is so close to your face and you pull the trigger and the plate goes forward and the flash goes off in the pan and there is time for you to flinch before the main charge goes off and the ball leaves the muzzle. So you have to be absolutely not stoical, but sort of dispassionate about this explosion going off right next to your eye if you’re actually going to be accurate. Yeah, the pistols are great fun too. But the musket itself. Oh God. It’s just gorgeous to shoot.

MT: And much more fun than any modern arms, I find the effort necessary to get them to work and become accurate with them very rewarding.

GW: Yeah, even just the physical sensations from them, like the recall from black powder is like a kind of a friendly thump in the shoulder, whereas the recall from a modern round, it’s much more like getting slapped really hard.

MT: Yes, much higher velocity and quicker burning powder. So it’s less pleasant, louder, and more of a crack to it that’s much worse for the hearing.

GW: Yeah, I like pretty much all guns, but the black powder thing is something special. OK, there are all sorts of horrible laws about black powder and stuff here in the U.K. So how does one go about getting to play with black powder in this country?

MT: Well, the usual way is to find a club where it’s taught; shooting of black powder weapons. Apply to be a member of that. And there’s usually a probationary period where the club will attempt to weed out anyone who is dangerous or a lunatic or whatever. If one passes a probationary period, one can then apply for a licence, which would be either a shotgun or a firearm depending on whether you’re looking for a smoothbore weapon or something else, and to actually get the black powder, you need a separate licence for that one to acquire it, another one to acquire and keep it because storing it is potentially risky. It’s explosive.

GW: I mean, that’s what Guy Fawkes was trying to blow up the houses of Parliament with.

MT: Well, quite, yes.

GW: Actually, given the government we’ve got right now, I’m pretty much on Guy Fawkes’ side.

MT: They are probably ready for that sort of thing now.

GW: Now, do you think they’d noticed me rolling thirty barrels of black powder into the basement under the House of Commons?

MT: You would never get over that now, but 30 barrels would produce quite spectacular results.

GW: Do you find any sort of connection between the rifle shooting and the guns in general to historical martial arts? Other than Napoleonic reenactment?

MT: Well, I have been looking at other historic things, such as 1850s revolvers, for example. There are a few texts about the use of those. Sir William Hope mentioned pistols. His advice for shooting with those you can find in historical texts. But one thing I’ve always thought is that rather than just pick and choose a bit of sabre, that’s cool, some rapier, a bit of long sword, as I get the impression people do, I’d rather do everything from the time. So I think I ought to know a bit of pugilism, I at least ought to have a little knowledge of wrestling. I’m absolutely rubbish at it and I would lose very quickly in a wrestling bout or to understand a sword, a musket. All of these things. Just to have some idea of everything that was about for that period, rather than pick and choose things from different periods. And so the knowing about the guns is part of that. If I wish to use a 19th century sabre because if I wish to do 1870 re-enactment, I also ought know how to use the revolver. I do First World War re-enactment as well, as it happens. So I do First World War rifles and shoot with those.

GW: One can’t do everything from the period, one doesn’t also necessarily spin one’s own thread. Plenty of people do that. And we’ve had people on the show who’ve done period knitting and period cookery. And there are all sorts of the non-martial-arty bits. But particularly if you’re training a military art, it doesn’t make sense to just pick one weapon when, for example, the knight would know the sword and the dagger and the axe and the spear and be able to ride and do all that stuff on horseback. Not everyone obviously can learn to ride as it’s expensive and it’s hard to find horses. And armour is also incredibly expensive. So there are all sorts of barriers to that. So it’s not necessarily always a practical goal, but there’s sort of a desirable goal that you would do as much of it as you reasonably could from that period. Including the clothes, as they affect how you move and the furniture is different and yeah, I’m with you on that.

MT: And I know you mentioned the medieval stuff. If I was interested in that era and I had the time or the money, I would be doing all those things. Looking at armoured, unarmoured combat, mounted, not mounted, various swords and lances and axes and whatever else. But I’m not really into that. So I stick to the variety of weapons and so on from the period that interests me.

GW: OK, so that sort of begs the question, what is it about the period? Hope goes from 1680s to early 1700s. Then you talked about Waterloo, which is 1815. So that’s like a hundred and thirty years or so that piqued your interests.

MT: It goes on further than that and at least the 1815 stuff is technologically not really much different. Those same flintlock muskets would have been in use a century before, for example. It’s very interesting between 1850 and World War One, lots of really cool weaponry and military technology occurs then, both at sea and land. It’s all really cool. And I would do more of this if I could and the time permitted. But it just doesn’t.

GW: But you’re not attracted to the stuff that was going on earlier, the early 17th century, 16th, 15th?

MT: English civil war is quite interesting. There’s some cool stuff there, but it just gets slightly less interesting as it gets earlier. I can’t really say why.

GW: It’s just a taste thing. That’s cool. I lose pretty much all interest in Italian art after about seventeen hundred or so, it’s like they all forgot how to paint. There’s going to be a bunch of people who are going, “Oh no, Guy, you are totally wrong. There are some great artists.” Yeah but I look at their stuff and it’s like, meh. I’ve been to the Vatican museum and in many other museums in Italy and they are all absolutely fabulous up until about 1700 and after that, it just leaves me dead. I could just walk through a room of supposed masterpieces from the late 18th, early 19th century or whatever. But walk into one of the medieval rooms and it is like, oh, my God, this is amazing, it just blows me out of water. And there’s no explaining it.

MT: So I don’t think I can even try. Some of these things are interesting. At least over that period that I mentioned there is a good range of interesting things to study and a lot of change. That picture certainly accelerates rapidly in the second half of the 19th century.

GW: Oh, yeah, sure. In the 18th century, as you said, the firearms don’t change very much. Fencing doesn’t change very much. A smallsword treatise from the end of the 18th century is pretty damn similar to one at the end of the 17th century.

MT: Well, there wouldn’t really be much need for any change.

GW: Do you think the smallsword is therefore the perfect pinnacle of the art?

MT: Well, I wouldn’t put it like that, but within the purpose for which it’s designed, it does the job nicely.

GW: It does the job very nicely. OK. All right, so I have a couple of questions that I tend to ask all of my guests, and the first one is, what is the best idea that you have not acted on?

MT: That’s quite a difficult one to answer, for a start, because I don’t have very good ideas. And secondly, because if I have ideas, I would generally act upon them if possible.

GW: Do you know about a third or so of my guests, that’s basically the answer. It is like, if it was a good idea, I’d have acted on it, so I don’t have any. That’s a perfectly legitimate answer to the question.

MT: Not a very exciting answer, I’m afraid. But there is nothing I could think of that I wish I’d done that but didn’t.

GW: Well, fair enough, the listeners have had Ken Monschein’s PhD thrown at them, so it’s been a fascinating hour for them anyway. I don’t think they can get too snippy about you not having a good idea that you haven’t acted on. So my last question is, you have a chest of doubloons or similar large sum of money with which to improve historical martial arts. Important caveat. You cannot spend it on your own gear. How would you spend it?

MT: When you say you cannot spend it on your own gear, do you mean your own HEMA gear like buying more swords and other such stuff?

GW: Exactly.

MT: Right, well, could I spend on my mortgage then?

GW: No, that would not improve historical martial arts.

MT: It would because I would give up my job and start teaching all the time.

GW: OK, OK, all right. But we’re talking about like say a million quid. And I’m assuming that your mortgage is not a million quid because I don’t think anyone would give you a million pounds worth of debt, would they?

MT: No, no, it certainly is nowhere near that bad, although house prices around these parts are not particularly cheap, unfortunately. But that will be one thing is a big problem with this is I don’t think it really pays. The people I know who are professional teachers of martial arts or of music. There aren’t very many of them. They have to work very, very hard to be able to sustain any degree of income from it.

GW: Yes, this is very true. Tell me about it.

MT: It’s not an easy thing to do, whereas for the stuff I do now to pay my bills, it’s actually fairly easy to turn up and say, oh, you want this work doing, here are my skills, I’ll do it for you, it will cost you this much. And there’s not really much effort involved in that comparatively, I think, to being self-employed in one of these areas where people aren’t really that keen to pay you, if that makes sense. So I would rather not be doing what I’m doing, but doing various things such as teaching fencing, perhaps writing another book, writing some software on the side.

GW: I forgot to mention your book in the introduction. I do beg your pardon. Please tell us about your book before you move on.

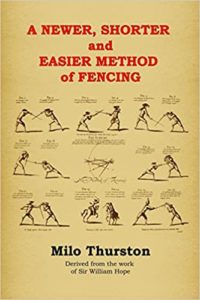

MT: It’s a very, very slim book about Sir William Hope’s fencing, because a lot of the complaints I got from people when I suggest they read his New Method or anything else is, oh, no, it’s really fat and thick and he waffles on for paragraph after paragraph of rambling nonsense. I don’t understand any of it. So I made something that’s on purpose quite thin that had some photographs in it so that people could read it and they would actually look at his stuff. And it’s got some quotes from him in it because they’re generally very entertaining and useful.

GW: It basically explains how to do Hope’s New Method of Fencing. So anyone who has had their curiosity piqued about Hope’s New Method of Fencing by listening to the show should definitely scurry off and buy your book immediately. We will put a link to that book in the show notes. Trust me, one writer to another, you can’t afford to be shy about your published work.

MT: It made me actually 15 pounds over this last year.

GW: Wow, that’s amazing. Oh, my God.

MT: I think I get more from the other book that I did with Phil Crawley.

GW: Which one’s that? Is that the Girard translation?

MT: It is, yes. Translation of Renaud’s La Défense dans la Rue, which apparently a lot of people are interested in, but don’t read the French. It’s also very Edwardian type French.

GW: Yeah. It’s kind of Savate sort of stuff, isn’t it?

MT: Yes. We did get one complaint from one person who bought it saying the language was dreadful. It read like a Chinese washing machine instruction manual. A dodgy thing to say, but I think the thing was that when we translated that we attempted as far as possible to maintain the sort of language and so I would say things like “and when circumstances require the immediate chastisement of a ruffian who’s accosted you in the street, you should at once make use of this method which will allow you to resolve the encounter without dirtying your clothes or having to go to the floor” and all that sort of thing. It sounds a bit formal.

GW: And I guess if people don’t expect it, if they’re expecting a modernised version. I find that when I’ve written a book and it goes out, it normally gets plenty of positive reviews because I’m very careful to make sure I get a bunch of beta readers in my target market for that particular book to read it and tell me what’s wrong with it so I can fix it. So I know it works for the people who it’s intended for. So then when inevitably it does also pick up some negative reviews, that’s always because I’ve sold a book to the wrong person. And so that’s a marketing problem, not a book writing programme. So then sometimes I’ve gone in and changed the blurb and the marketing copy for the book and maybe some of the keywords to make it clearer what it is and what it’s not. And just because if the people you wrote it for love it, then if someone was giving you a bad review is because you sold the wrong person a book.

MT: Well, quite likely in this case, I don’t think we really pushed it particularly hard, it’s there for anyone that wants it.

GW: OK, I will definitely put a link in the show notes too. And hopefully you can retire on the proceeds, pay off your mortgage and become a full time fencing instructor as well.

MT: Well, sort of full time. A bit more like Sir William Hope. He could go to the salle three times a week, go horse riding, dancing and go off to his club or whatever as he saw fit.

GW: But I mean, he was the deputy governor of Edinburgh Castle at one point wasn’t he?

MT: For a short time.

GW: He is a posh dude.

MT: Ian Macintyre has done a bit more research and he gave us a good lecture at the Smallsword Symposium one year about William Hope’s history, which we don’t have time to go into, if I could remember it all right now. But he said loads of interesting stuff about the possibility that Hope actually killed someone in a duel and what evidence there is for that. And some of his comments in his last book about vindication might relate to that. There is a bit in that where he says, some people might ask, how would I come to know so much about swordplay if I’ve never fought with sharps, I’ve never killed anyone. And his response is, well, if I have fought with sharps that’s none of their business and I’m not going to answer it, and it would be vainglorious to boast of it if I had. And even if I haven’t, I’ve had the practise of near 50 years with foils, so I know what I’m talking about. Get stuffed. This is what he says, to paraphrase him.

GW: Excellent. OK, so basically you would spend the money setting yourself up so that you could live as Sir William Hope lived. Riding and fencing. I’m not sure that would necessarily improve historical martial arts much outside Oxford.

MT: It might. One of the things I would do as part of that is look into nicer spadroons and other such things, which they would be more generally available. Another thing I know is I like a bit of sabre. My favourite sabre is an 1855 pattern French officer sword, which is a nice weight, nice length, balance, but nothing that’s on the market today, if you can find it for sale, things always seem to be sold out, is anything like it. Everything is too heavy and the balance too far forward and hurts my elbow when I try to swing it so I don’t get a chance to do any nice sabre work these days. There’s just nothing really good to do it with.

GW: OK, so you would finance the production of accurate to fencing safe replicas of these.

MT: So I don’t necessarily think the ones that exist are inaccurate, but they are a different sort of weapon, really.

GW: OK, if they don’t match the handling, then they’re not accurate in the way that we would need them to be.

MT: Well, I think they match the handling of generally heavier sabres. I was at a test cutting event this weekend, for example, and a variety of sabres, British 1803, for example. Very light indeed. Perfect for me to handle. My 1855 is slightly heavier, but still an acceptable weight. And some European swords and an 18th century American style cavalry sabre. Dreadful. One or two swings and my elbow would be utterly knackered or I’d be exhausted, not able to use them further. But they’re not bad swords. They’re just not ones I can handle because the weight is too high for me. My elderly and knackered elbows cannot handle it. And so something that would cater towards that sort of.

GW: Yeah. Modelled on your 1855 perhaps.

MT: Yes. One of those that would go down well I think, or the 1803.

GW: Now and my favourite cavalry sword, or sabre of any kind, I would say, is the 1796 light cavalry sabre, the British one.

MT: I’ve handled some of those. Very nice.

GW: I have one, it’s very, very rusty. I mean, I didn’t let it get rusty, it was bought like that, but I got it when it was already pretty worn out. But I just had to have one and I got fairly cheap because it was in not very good condition. But it still handles. I wouldn’t cut with it because I wouldn’t want to sharpen it because there’s so much pitting and stuff on the blade. It would just be a mess. I do solo stuff with it sometimes, it’s just lovely. It is light and responsive and accurate. But the authority behind it, it’s just it’s horrendous. You would take somebody’s leg off.

MT: I would not be surprised. Some of the stuff we’re seeing done with curved sabres over the weekend is quite nasty. It’s much harder to cut with a straight sword.

GW: Yes. And there’s a whole bunch of interesting physics going on there, which I don’t understand at all. And I have a theory as to why curved swords cut better than straight ones. And a physicist friend of mine, or was it an engineer, basically told me I was completely wrong and I believed them. But I cannot possibly explain why these curved swords cut better. OK. So thank you very much for joining me today, Milo. It’s been a delight catching up with you again.

MT: Thanks again, it’s nice to give me a chance to waffle on about stuff, a shame if it’s not in person in a pub.

GW: Indeed, let’s do that next time.