GW: I’m here today with Neil Melville, author of Two-Handed Sword: History, Design and Use, and an avid collector of antique swords. So without further ado, Neil, welcome to the show.

NM: Thank you very much. I’m quite intrigued to be here.

GW: I should perhaps mention to the listeners that Neil told me in the pre-interview chat that this is his first ever podcast as a guest. So doubly welcome on your first show, it probably won’t be the last. So just to orient everyone, whereabouts in the world are you?

NM: I live in Stirling, which I’m sure everybody knows is the gateway to the Highlands. In fact, it’s the bridge where, up until almost modern times, everybody had to go through Stirling that was going north. That means all the armies, kings, troops, supplies, everything going north or south had to go through Stirling. And so Stirling Castle was a very important feature.

GW: So is that why the Battle of Stirling Bridge between Edward III’s armies and William Wallace and Robert the Bruce’s Scots was so important?

NM: Exactly. Yes.

GW: OK, good to know. Oh yeah, I lived in Edinburgh for a long time, but I hadn’t quite twigged on Stirling’s strategic importance in that regard.

NM: We’re sort of halfway between Edinburgh and Glasgow and slightly north of that line.

GW: So I guess living in Stirling, you’re surrounded by medieval history, is that what got you started with swords?

NM: No, I started with swords when I was at school, really. And I was in school in Yorkshire. I can vividly remember having a history exercise book and somehow or other, I’d managed to actually cover it with drawings of swords. So quite how that came about, I can’t be certain, but there we are.

GW: Well, I think it’s natural and normal. I have notes and I have a list of questions and things, and I keep making notes as we’re talking and very often my notes at the end of a podcast interview, are just covered in sword doodles. I think for some of us, it’s just a natural thing to do. It just comes up. So how did you really get started? When was the first time you picked up a sword?

NM: Well, I was interested in them. I read books on them. I found pictures of them. I took photographs when if I was in a museum. And then it developed into collecting swords. Shall I mention the story of how I got my very first one?

GW: Yeah, go ahead.

NM: I had actually just finished my degree and I was going for an interview for a job in Nottingham, in fact. And on the way to the interview, I passed an antique shop which had what seemed to me a fabulous sword in the window. I was scared that either the shop would be closed or somebody else would buy it before I could get back. So I went and bought it, it cost about three pounds, I think. It was a 1796 light cavalry sword.

GW: You’re kidding. That’s one of the best swords ever made.

NM: Yeah, yeah. But it’s a long time ago. That’s why it was so cheap. Again, I went and bought it. The proprietor wrapped it up for me. Then I went off to my interview, realising that actually carrying this into the interview room might not be the method of success. I got the secretary in reception to hide it for me while I went in and I collected it on the way back. And I’ve still got that sword, I’ve bought several other since which I’ve since sold, but I’ve still got that one.

GW: Well, yeah, you never forget your first do you. So did you get the job?

NM: No, but I don’t think it was anything to do with the sword.

GW: No, no. But also, the sort of place where you would have to hide the fact that you’ve got a sword with you on going into the interview is probably not the kind of place you really want to work anyway. OK, so you’ve written this book. I mean, let me just be completely frank, my friend Paul Wagner, who I interviewed on this show a little while ago, after he’d interviewed me, he said, Guy, you really ought to get, Neil Melville onto the show because he’s written this amazing book called . I must confess, I haven’t actually had time to read it yet.

NM: Oh, you must!

GW: Yes, exactly, exactly. What kind of slack podcast interview am I when I don’t read every book written by every one of my guests? Paul Wagner is very well known in our community and very highly respected. And he said, Guy, you’ve got to talk to Neil. This is why you’re here. And Paul loves the book.

NM: I am glad about that, anyway.

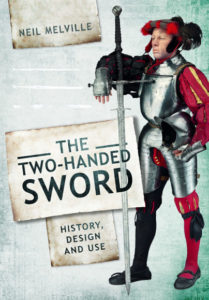

GW: Yeah. Tell us, tell us about the book and what it’s about, what it contains. Go ahead.

NM: Well, it’s basically a history of looking at the sword, the development of the sword from very early times until it, well, it’s still in use as a historical fencing weapon. But over the of the time I was doing it, I have been sort of working on this, probably for 30, 40 years, just on and off gradually. I do the origin and the development of the sword. Then I look at the general form. How is it different from a single handed sword? I look at various different styles, which I hope I can locate to various regions or even nationalities. I consider how people actually fought with the two handed sword, both in one to one combat, as in duels or even practised fencing. And then also how it was used in combat actually on the battlefield. I consider fencing, duelling, tournament use, which is not quite a sideline, but away from the main thrust of combat. I come on then to it’s development as a status symbol and its significance in the aristocratic household and the aristocratic community. I try to get as many illustrations of everything as I’m trying to talk about and also stuff that I found in foreign language sources where I can read the language, but my biggest problem actually has been that I don’t read German. I’ve got the basics. You know, sort of 20 or so individual words, but I can’t string them together and I don’t understand when a complex technical item is being discussed in German. However, on the other hand, I do read French, Italian and Latin.

GW: Can we have these terms like bastard sword, longsword, two handed sword, Zweihander, montante, and so on. So when does a bastard sword become a long sword, become a two handed sword? Do you have sort of categories worked out?

NM: Yes. Well, one of the one of the problems is that these categories didn’t really exist, as such. It has been a continuous development from the 13th century right up to the 18th century. And some of these terms, of course, never existed in their own time. Terms like Zweihander, for instance, or hand and a half sword. These are modern terms.

GW: OK. So, all right, but in your opinion, then what is the difference between a longsword and a two handed sword?

NM: If I start at the other end and say that it’s not, as I’m concerned, a two handed sword has got to be wielded with two hands. It cannot be wielded with one hand, it’s too heavy, too long. It specifically needs two hands to wield it. It can be wielded much more easily and effectively if the hilt is long enough that the two hands can be separated, not touching each other or even overlapping so that you get a sort of fulcrum effect over the middle of the hilt with one hand pushing, and the other hand pulling.

GW: OK. All right. Fiore explicitly says in Il Fior di Battaglia, no I beg your pardon, it’s Vadi. Vadi says in De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi that there should be space on the handle for three hands. In other words, the grip is as long as at least three palm widths. So you could get three hands on if you have three arms. Is that sufficient, do you think, to make it a two handed sword?

NM: Yes, I think so. So that as I say, the development is gradual. Around 1300 smiths were able to make longer blades. The steel technology had advanced to the point that it would make longer blades. And obviously, people found this could be more effective. They could deal heavier blows. So at this point, you get what you could call the war sword, the epee de guerre, or the great sword. These are what I would consider blades of, say, 90 centimetres, 90 to 100 centimetres, hilts of perhaps 20 centimetres. As technology improves on us, as warriors found the use of this sword, which of course, is always going to be much more expensive, then it grew in size. The term longsword causes a lot of problems. I’ve had discussions with people who claim that this is a long sword or that is a longsword, and that’s not a longsword. “Longsword” in the sources seems to be used to cover virtually any sword, which is longer than a single hand sword. Not a specific category or a specific size. So we go through the war sword to a sword, which nowadays might be called the hand and a half sword, although, as I say, that was not used. It’s a modern term. The sword basically can be wielded with one hand, particularly say, on horseback where the warrior needs a longer reach. But if he’s dismounted, it can be used on foot, perhaps with the addition of the second hand on the end of the grip or over the pommel to get extra force. Not particularly to aid in the wielding of the sword, just to add that strength. Then around the middle of the 14th century, certainly nearer the end of the 14th century we get some swords, which I think can be described as real, two handed swords. Not very many. But there’s one or two which can specifically be dated. For instance, there’s one in Istanbul, which was previously in Alexandria and was dated when it was deposited in Alexandria to 1368. And this is a two handed sword. It’s got a blade over a metre and a hilt around 30 centimetres.

GW: Wow, definitely a two handed sword.

NM: Yes. Swords of this size become improved. They become defined for a specific purpose. In the end, of course, we end up with a variety of swords with fancy hilts, with extra parrying lugs on the blade, with side rings at the hilt. These are still being used in combat through really up to just past the middle of the 16th century. It’s been said that the Battle of Pavia and 1525 was the high point of the use of the two handed sword. The tapestries in Naples have some absolutely splendid examples of warriors wielding two handed swords in the battle. But by the end of the 16th century, we’ve now got swords of such a size, 170 centimetres and so on, which really can’t be used in battle. They’re too heavy. I found that just in basically in doing my research, that battle swords, if you like to call them that, from the 15th into the into the first half of the 16th century, they average about 2.3 kilos in weight and in total length around 150 plus centimetres with a blade of around 110 centimetres. These are real two handed swords. They can’t be used with one hand, but they can be used in battle and were used in battle. After that as they got even bigger I think they fell out of use for combat. They were just too big. But on the other hand, they were used as status symbols. A lord or a commander or governor general could be surrounded by men wielding these massive swords and that added a prestige to his position.

GW: OK. Because, yeah, I’m familiar with some of the early 17th century Portuguese sources which deal with Montante. And this seems to be explicitly a bodyguard weapon.

NM: Yes. The accounts that we have from that period show that mainly, certainly by the early 16th century and probably earlier than that, the two handed sword used as a mass weapon. In fact, I don’t think it was ever used as a mass weapon. For one thing, needing the space to wield it meant that you couldn’t you couldn’t have a load of comrades standing next to you.

GW: So just to be specific about mass weapon, you mean a weapon used in a group of soldiers? Like a pike.

NM: OK. Yes, exactly. So it seems to have evolved fairly quickly into a weapon you used to use as a bodyguard. To guard the ensign or the commander or various officers. And we have some of the German accounts that describe the numbers of different types of swords in the army where you’ve got perhaps a body of, say, 200 pikeman, but only 20 two handed swordsmen.

GW: Right, OK. Interesting. So I think because Fiore in his Il Fior di Battaglia around 1400 and he shows a sword, which is most often used for two hands on the weapon, but there’s an entire section of the sword being used on foot with one hand, and that is what I think of when I think of as “longsword”. And to my mind, that is clearly not a two handed sword because it is used in one hand. But Fiore describes it, yes, he says, it’s a spada e due mane, which is a sword of two hands. And then later on, we have the spadone, like the great sword, the big sword, in 16th century Bolognese sources, which is very clearly a what we would think of as a two handed sword. So you couldn’t really carry it as a sidearm in a scabbard on your hip. It’s just way too long.

NM: I was going to say that the trouble is, there’s the whole lot of confusion about terminology, whether people refer to two handed swords when they’re not really two handed swords. And this carries on right up to the modern day. Modern books can refer to a two handed sword, and I look at it and say, that’s not a two handed sword. This confusion goes right back to the 15th century, as you say, with Fiore. I refer to his illustrations of swords as being two handers. But I accept that there are occasions when some of his pictures show the sword being wielded with one hand. It’s just one of those ambiguous stages.

GW: Well, I mean, to my mind, his sword is about maybe 120 centimetres long. You can certainly use it with two hands. And he explicitly calls it a sword of two hands. So it can’t be wrong to call it a two handed sword if the author of the manuscript calls it a two handed sword. But that’s more of a I would call long sword rather than two handed because in my head to have a two handed sword is something that is not really a sidearm. You don’t carry it in a scabbard on your belt. It’s something that has to be actually carried like a rifle. Whereas a longsword is a is a long version of a sword that can be carried on the hip.

NM: Yes. Well, as I said earlier, the term longsword can be applied to do anything that’s longer than that. So I think that modern practitioners of historic fencing have sort of taken over this term and used it for their own purposes to describe that this particular sword, which is say, as you say, about 120 centimetres long and perhaps a blade of just under a metre.

GW: Yeah, guilty, as charged. Absolutely. Because we’ve got to have a simple name for this thing. And all of us doing historical fencing get what we mean when we say it’s a longsword, right? As different to two handed sword, as different to an army sword or rapier or some other kind of sword? But yeah, like many of the sources, they just call it sword. So when Vadi writes “spada” he means “sword” as in the sword that he’s talking about. And Cappoferro who’s very clearly talking about rapiers is describes his sword and actually describes its length in some detail, he just calls it a sword. He doesn’t call it a rapier or any fancy term. It’s just sword, because that’s what a sword was for him in that culture at that time. So, yeah, we’re trying to basically make definitions that didn’t exist in period.

NM: And everybody’s got their own definition, or not everybody, but there are different definitions flying around. And there’s just no accepted status of nomenclature, I’m afraid. And we all make our own definitions, including me.

GW: I don’t have a problem with that, I think that’s a perfectly reasonable normal thing to do because we’re starting a new field of historical study, which had been going for about 25 years now and maybe 30 years. And it’s going to be a while before everyone settles on definitions. If you go into museums now, you can find Bronze Age swords. If they’re particularly long and thin, they get described as rapiers.

NM: Yes. I know, I’ve seen them.

GW: It’s not a bloody rapier. It’s a bronze pig sticker, they’re like two and a half feet long or something. It’s just because they’re a bit longer than a normal bronze sword and they’ve got a thin blade rather than a wide one, they’re called rapiers. No, they’re not rapiers.

NM: Yes, but you try telling that to the general public or even some museum curators.

GW: Right. Yes. OK, now just return to Paul Wagner for a minute. Who’s in episode 69 of the show. Because he suggested I invite you on and I’m very glad that he did. I asked him, is there anything you particular want me to ask Neil? And he replied back with a very long question, and I will read you the whole thing. And then then we can see if we can satisfy Paul’s curiosity on this point. OK. Brace yourself. All right. Paul writes, I need to do this in an Australian accent but I can’t. “Despite the obscurity of the English longsword sources I work with, I do have the great advantage of knowing exactly what kind of two hand swords they are using, thanks largely to Neil’s sterling research. So the Harleian manuscript, for example, dates from 1450 ish. Maybe a little earlier. And the swords in use at that time, such as those from the Castellon Horde, are considerably longer and heavier, i.e. 140 to 150 centimetres, two to two and a half kilos than the standard Feder generally used by modern practitioners, i.e. 100 centimetre blade, 30 centimetre grip, 1.6 kilos in weight. From what I can tell most 15th century two hander are I like that. While I’ve personally come across a few real swords of those kinds of dimensions, they’ve always been a little shorter and significantly lighter. True bastard swords easily used in one hand, including, by the way, a pair of genuine feders. So I’ve always been sceptical of the standard feder. They seem to be neither one thing or the other. And from my conversations with smiths, they are that size because that’s as long as most of them could get tempered and that weight for robustness so they don’t keep breaking. I’ve also heard a lot of modern practitioners, particularly of German citizenship, argue about this. Half of them swear it all works better with larger swords. Half has a contrary opinion. So the question is – thank God he’s finally got to the question – are there many or any two handed swords out there that correspond with the standard feder? Or is everyone using the wrong weapon? If so, what should medieval long sword fencers be using?

NM: Right. Yes. I take it that by standard feder, he means the sword that modern historic fencers are using?

GW: Yes.

NM: All right, well, the big problem is that although a number of original fencing swords, federschwert, do survive, museums and catalogues in general seem very reluctant to give their weights. They’ll usually give a size, but we have to guess their weights. So what I’ve been able to find is that genuine federschwerts are probably similar to what Paul is talking about, but perhaps a bit bigger, somewhere between 1.3, 1.6 kilos. The total length of 130, 135 centimetres, the blade around 100 or just over 100 centimetres. Whereas fighting swords of the period, of the mid 15th century, seem to average a good bit more than that around two and a half kilos. And about 1.5 metres long. So depends what your modern fencing practitioner wants to do. If he wants to fight with an original 15th century sword. I mean that sort of sword, then he’s got to use one that’s two and a half kilos heavy. If that’s too heavy, if he wants to use the sword that the fencing schools as Meyer and Marozzo showed, then, yes, a modern feder of about what does he say, 1.6 kilos? That’s probably OK. But so long as you appreciate that when you when you fencing with a federschwert, you’re not imitating a battle or combat, you are just fencing.

GW: So it’s like the relationship between a modern foil and a smallsword?

NM: Yes, yes, I think that’s probably right. I mean, a modern sport foil weighs well under half a kilo, 0.38, 0.75 of a kilo. It’s very light indeed. And even an epee, which is slightly heavier, is still under half a kilo.

GW: That’s not heavy at all. OK. So I heard a theory once that the federschwerts were often made from when a sharp proper sword has been basically worn out and the edges get ground off and the point gets ground off. So the expensive steel is not wasted. And maybe the hilt is adapted to the now much lighter blade. And that’s how the federschwerts were made, which is why you have those broad lugs next to the cross guard. So what do you think of that theory?

NM: Not much. The federschwerts that I’ve seen, the blade is flat is quite broad. It broadens out, in fact towards the tip, which is squared off. I can’t see it having been cut down from a real sword at all. I mean, the whole blade would have had to be thinned down, which seems pointless if you can just make one from scratch, which I imagine would have been much easier. And also the sort of square block ricasso, how’s that going to be to be carved out from an original real sword?

GW: OK, fair enough. So theory entirely blasted. I’ve got another one for you, this is this is something that I was told long, long, long time ago. I won’t say who said it because, you know, that’s not fair because we were young. One of the uses of a two hand sword in battle was to go around, basically cutting the heads off pikes.

NM: Yes, I’ve come across that. In fact, a lot of the books still repeat that. And as far as I’m concerned, it again is rubbish. Well, there are various reasons. The pikemen are packed tight, they are in several ranks. Eight, possibly even 16 ranks. You, as a two handed swordsman have got to be on your own because, well, your nearest companion is going to be, say, four metres away from you. So you wade into the pikes, you cut off a couple of heads and then you’re dead because there are far too many pikemen for you to deal with. So that’s one argument. The other one is that trying to cut off the head of a pike, which is perhaps 16 or 18 feet long, and it’s is only held at one end. It just doesn’t work. They sword would just bounce off, or the pike just bends around. Well it doesn’t bend, it sways out of the way just because at the end which you’re trying to cut off is not supported.

GW: Also I’m a woodworker. The idea of being able to cut out through, shall we say, an inch diameter of ash, which is probably ash on a pike handle, maybe oak. The idea of being able to cut through dry wood at that dimensions with a sword in a single blow. It’s really, really unlikely. I mean, I certainly couldn’t do it.

NM: Well, apparently people have actually experimented with trying to do that. And as you say, it doesn’t work.

GW: OK, well, good, I’m glad that my bullshit detector was pinging for good reason. I’m a bit sad about the feders not being ground down from sharp swords because that appealed to me for some reason. I can’t say why, but it just did. OK, now I know you’re a collector. And when I first approached you about coming on the podcast, you mentioned some of the swords in your collection and you actually have a couple of two handed swords and some medieval swords. We know how you got started, you saw 1796 pattern cavalry sabre in an antique shop, and you went in and bought it for three pounds. I know it was a long time ago, but it’s probably worth, I don’t know, several hundred times that now. I have 1796 pattern cavalry sabre and it is not in very good condition because it was like that when I bought it, but it’s just a fabulous, fabulous sword. So I totally get why you went for 1796. Who could blame you? But how did you get into the rest of the collecting thing? A lot of my listeners and friends, they really want to get antique swords, and they are hard to come by these days.

NM: Yes, indeed. Unless you’re prepared to pay a lot of money at the auction houses. I got into it basically I was still in my first job, I didn’t have a huge amount of money. All that I could afford were sort of 19th century regimental swords. So if I could pick one up for a few pounds, obviously, it was increasing from three to up through 20, 40, 50, 60 pounds. If I found one that I liked and I could afford it, I bought it. And then of course, once you start, you say, well, there’s all these different patterns. As you say, there’s 1788, 1796, 1820, 18 50 odd and so on. You think, I need one of one of that pattern to complete the set, and then I need one of that pattern right up to the 1908 pattern. And I’ve got virtually one of each of each British regimental pattern just through over a long period of time, picking up ones that I could find, ones that I could afford. Then as my financial position improved, shall we say, I took a fancy to earlier swords, especially if I could get one going, not too not too expensively at an auction. And so it developed into 18th century, 17th century, one or two. I just kept going. I very rarely seem to be able to sell a sword, and so I’ve just now got quite a lot.

GW: Well, my experience of having swords is I’ve never regretted buying one, but I’ve often regretted selling one.

NM: Yes, yes, I can understand that. I sometimes regret not having bought one when I could have, for whatever reason.

GW: Yeah, how do you how do you find genuine two handed swords to buy? Where do you get them from?

NM: The recent ones I’ve found I’ve been at auction sales. The Swiss one I got most recently was at, can I mention the name of the company? It was a Tom del Mar auction just over a year ago. I’ve got an Italian one, which I got at an auction in Edinburgh about six or seven years ago. So those are my two handed swords. But basically it seems to be auctions. A few, obviously, you come across dealers, you make “friends” with dealers. And if they’ve got something handy, which they think you might be interested in, that they let me know. And I can say yes or no. I’m now in the financial position where I can be a bit more selective and go a bit deeper into the market. So basically auctions, but some dealers as well.

GW: OK. Because we’ve had another collector on the show, who you may know, actually, I’m not sure, Malcolm Fair, who runs the National Fencing Museum near Worcester.

NM: Oh yes, I know of him, though I’ve never actually met him.

GW: He collects fencing books and fencing memorabilia and equipment and swords going back to around 1700. He’s got dozens and dozens and dozens of these swords and foils and epees and he has what is probably the best collection of historical fencing books in private hands in Britain, possibly in Europe. Although I have a colleague in in Italy, whose collection may be better than Malcom’s. I don’t know, but it’s an amazing, amazing collection. And yeah, his story was very similar. He started pretty young with not much money and got lucky a couple of times and made acquaintanceships and friendships with dealers. And then just showed up to a lot of auctions and often didn’t manage to get anything because he was outbid and every now and then got lucky and like 50 years later, he has this stunning collection. So, yeah, I guess for people listening, the time to start is now.

NM: Well, no, really the time to start was 50 years ago.

GW: Yeah, but that’s not an option. But if you put it off, it’s just going to get worse. It’s just got more expensive and they’re just going to get rarer because no one is producing more antiques swords. No one is producing more genuine antique swords, so the number of available weapons can only go down.

NM: Well, I suppose as people die and the collections get sold, that’s a fairly common source.

GW: Yeah, more swords will come on the market as they become available, but the actual swords themselves, you can’t make more of them because they are a finite resource. So they should just go up in value. I’m more of a sword user than a sword collector. I only have like four or five antique swords.

NM: Yes, I can them see on the wall behind you.

GW: Oh, yeah, only a couple of those are antiques, the rest of are modern reproductions for training. But I have a sabre there, and the smallsword. The smallsword is from about 1780, the sabre’s from about 1820. And they’re there for actually doing solo drills and practise with because they’re in good enough condition that that’s not going to do them any harm. But yeah, there’s absolutely nothing quite like handling an original sword. Just feels different. As you well know. But I gather you’re a sport fencer, which is not a bad thing. I didn’t mean that to swound pejorative in any way at all. I used to be a sport fencer and that gave me my start into it. But I gather you don’t do much historical martial arts, is there a reason for that?

NM: This is something I’ve sort of pondered with myself for a long time. It’s very odd. I was interested in having the swords, in handling them, wielding them myself, but I never really met anybody persuasive enough to get me into actual historic fencing.

GW: Would you need much persuasion? I make my living by teaching people how to do historical fencing. I’ve always had it as a kind of basic principle that if I have to persuade them to come to class, I’m not going to. If I have to reassure them that it’s OK to start even though you’re old or unfit or have a dodgy wrist or whatever, that’s fine. I don’t mind encouraging a person to try it even though they have restrictions or what have you. That’s fine. But if they’re not really sure it’s something they really want to do, then I don’t even try to persuade them because here’s this cool thing, and if you don’t want to do it, don’t do it, it’s fine.

NM: Yeah, I think when I started sport fencing, which was a university that came to take up more and more of my time, and I was reaching a level that I wanted to be better at. I was in a couple of clubs, I had coaching and I managed to actually reach the national team and there didn’t seem to be any sort of option to go into to the sideline of historic fencing, which wouldn’t necessarily have improved my sport fencing.

GW: It wouldn’t have improved it at all. Do you mind my asking how old you are?

NM: I’m nearly 80.

GW: That’s not too old, my grandfather was fencing in his 80s doing sport fencing and yeah, OK. There are certain aspects of historical fencing that you probably shouldn’t take up at the age of nearly 80. Maybe some of the armoured combat, that is pretty heavy and the wrestling is going to hurt. But I don’t see any reason not to swing a longsword around just because you pass a certain age. I’ve had students start in their 70s successfully before.

NM: Well, maybe I’ll think about it.

GW: Don’t think about it too long because you’re not getting any younger.

NM: Yeah.

GW: Okay, so I guess when the historical fencing thing really kicked off, you would’ve been in your mid-50s and it didn’t really get going for about five or 10 years. And so I can see why maybe seeing it when you’re in your sixties and going, you know what? Maybe that’s a bit too… well. At that time, in the 90s and early 2000s, it was mostly foolish young men like me at the time, whacking each other harder than they should with inadequate equipment. So I can totally see why starting at that point might not have been a good idea. But things have moved on a very long way since then.

NM: I’m glad to hear it.

GW: Well, tell you what, if I’m ever in Stirling, I will give you an introductory lesson and you see if you like it.

NM: Well, you’ll be very welcome anyway, regardless.

GW: I was doing a bit of research for this interview and I came across this gem in your bio. Apparently, you have also represented Scotland at skiing. Now, Scotland is not famous for producing skiers as far as I’m aware, so I have to ask what was going on there.

NM: My publisher is not famous for getting things right, either.

GW: Ah, OK.

NM: I take it you found that on one of the flyers for the book.

GW: Yeah, that’s where I found it.

NM: What happened was the publisher asked me, obviously, for a short bio to put on the cover of the book, and I just mentioned that I had represented Scotland on the piste. I thought it was obvious that it was a fencing piste and they took the piste to be skiing. They didn’t question me. So, there you have it.

GW: All is made clear because I was thinking when the hell did he ever have time to get to the national level as a skier, what he was doing all this fencing and I was like, huh? Right, right. Let that be a lesson to everyone listening. You can’t believe everything you read on the internet.

NM: Zooming downhill on skis with a sword in each hand might be interesting.

GW: That might be very interesting, yeah, we should invent the sport of ski jousting. I can see it now. You have two not too steep ski jumping type slopes or one like a skate park big enough for skiing, because the ski jumps are enormous, right? And you ski towards each other and you want to time it so that ideally you want to be going downhill and they’re coming uphill so you’ve got more power behind you and you if you meet in your equal. But if you’re a bit late, if they manage to slow down a little bit on the way down and you’re going uphill and you’re losing speed and they’re gaining speed coming up, that could be brilliant. I think we’ve just invented a new Olympic sport.

NM: Maybe we should get Toby Capwell interested from the jousting point of view, just put skis on him and set him off on a whole new trajectory.

GW: That is a brilliant idea. Actually, I interviewed Toby Capwell for a few weeks ago and his interview’s going out next week. We’re recording this on the 19th of October and it’ll be going out on the second Friday after that. So I didn’t mention it to him then, but he doesn’t live very far from me. And we do actually have a dry ski slope in Ipswich, where I live. So I’ve got Toby six miles away and a dry ski slope three miles away. Oh, dear God. This is a really, really bad idea. I don’t suppose, as a student you ever did wheelie bin jousting?

NM: No, no.

GW: Or bicycle jousting?

NM: I don’t think wheelie bins had been invented in my day.

GW: Fair enough. But bicycles had I’m pretty sure. Ever tried bicycle jousting?

NM: No. It could be painful if you fall off.

GW: It’s very painful, that’s the point. So basically, bicycle jousting uses brooms, usually because we’re students and we don’t have money for equipment. Bike helmets optional, because they were back then. And you cycle towards each other with a broom couched on your arm with the head of the brim forward. So you’re hitting with the point, you’re hitting with the wide bit so you can’t knock out somebody’s eye. And you cycle towards each other and boom! If you get it just right, they go flying. And it’s very dangerous and stupid, and you shouldn’t do it. But it was great fun.

NM: I would imagine both of you come off.

GW: Well, it depends how well you’re seated. I mean, there is there is the risk of you both coming off and that’s not an uncommon outcome because forces work in both directions.

NM: I think I’ll give that one a miss.

GW: Yeah, I think maybe that’s not something to take up in the 70s. You have to be below a certain age and a bit stupid to do it. But yes, it’s great fun. But yeah, I am not surprised that your publisher screwed up the bio. My experience of commercial publishers has been mixed bag. None have misrepresented my bio, but yeah, I can see how that could easily happen.

NM: At least it didn’t go into the book. The bit about skiing didn’t go into the book. It is just on the flyer.

GW: Yeah. You don’t have a very strong internet presence. I couldn’t find a great deal of official Neil Melville information. So I think I got that from the Amazon listings, the About the Book section on Amazon. That’s where it came from. Do you do any sort of social media or Twitter or anything like that?

NM: No, as I sort of hinted to you, we don’t do anything like that at all.

GW: Very sensible. It’s just, you know, some people, when they come on the podcast, they want me to direct the listeners to a particular web page or social media account, but there’s none of that. So what people need to do is just buy your book and read it.

NM: Exactly, buy as many copies as they can so that I get to the stage where I actually receive some royalties.

GW: That would be good. All right. OK, so our mission listeners, is to get buy everyone you know, a copy of Neil’s book for Christmas plus one for yourself so that Neil can get some actual royalties from the publishers. Brilliant. Well, thank you very much indeed for joining me today, Neil. It’s been delightful talking to you.

NM: Thank you very much. Yes, it’s been most interesting. How it will come out at the end, I have no idea.

GW: Well, we’ll find out. Brilliant.