Dr. Reinier van Noort is a martial arts instructor and translator of over a dozen historical fencing treatises. He now lives in Norway but is originally from the Netherlands, so we talk about his impressive skills in translating from one foreign language into another. You can find Reinier’s work at www.bruchius.com, and his list of publications here: Publications – Ense et Mente (bruchius.com).

We covered a lot in our conversation as you can see from the following notes:

Jägerstock

If you’re subscribed to my newsletter you’ll probably know that I have been working on the Jägerstock as promised in the interview. Reinier’s book that includes the Jägerstock is: The Martial Arts of Georg Johann Pascha. There’s also a free translation of the Jägerstock material here: http://www.bruchius.com/docs/Pascha%20Hunting%20Staff%20by%20RvN.pdf. The book version is a newer translation, based on a later text that has a few more lessons, and some better plates.

In my newsletter of 18th March I posted my first Jägerstock video: https://vimeo.com/688832535/a4fc0fa994 Please note, I shot it before I’d even finished making the proper Jägerstock, so I’m winging it with a bo staff. I’ve also got a longish video of me actually making the weapon (while musing on matters history and craft),

https://vimeo.com/698975685/b526163231

Another on lessons 1-3 with the finished weapon,

https://vimeo.com/698975706/2021cc549a

And several more in the works. My current plan is to create a course on my teachable platform (which will be bundled in with the Mastering the Art of Arms subscription, of course), where I’ll post the videos as they are made. And when I have a working interpretation of the whole book (which is 34 lessons, each one of which is a short form), add those to the Solo Training course as a new section, and also release the whole ‘from book to working interpretation’ series as an object lesson in how I go about the interpretation process with an unfamiliar source, style, and weapon.

Fabris and Capoferro

After the Jägerstock chat we also have a bit to say about Fabris and Capoferro. As mentioned in the episode, here is Reinier’s Fabris lecture: Longpoint 2017 – Lecture: From Fabris to Pascha – YouTube. Reinier says he has expanded the lineage a bit since the lecture.

We have a bit of a discussion about the lunge – read more on how to Max Your Lunge here: https://guywindsor.net/2022/04/max-your-lunge/

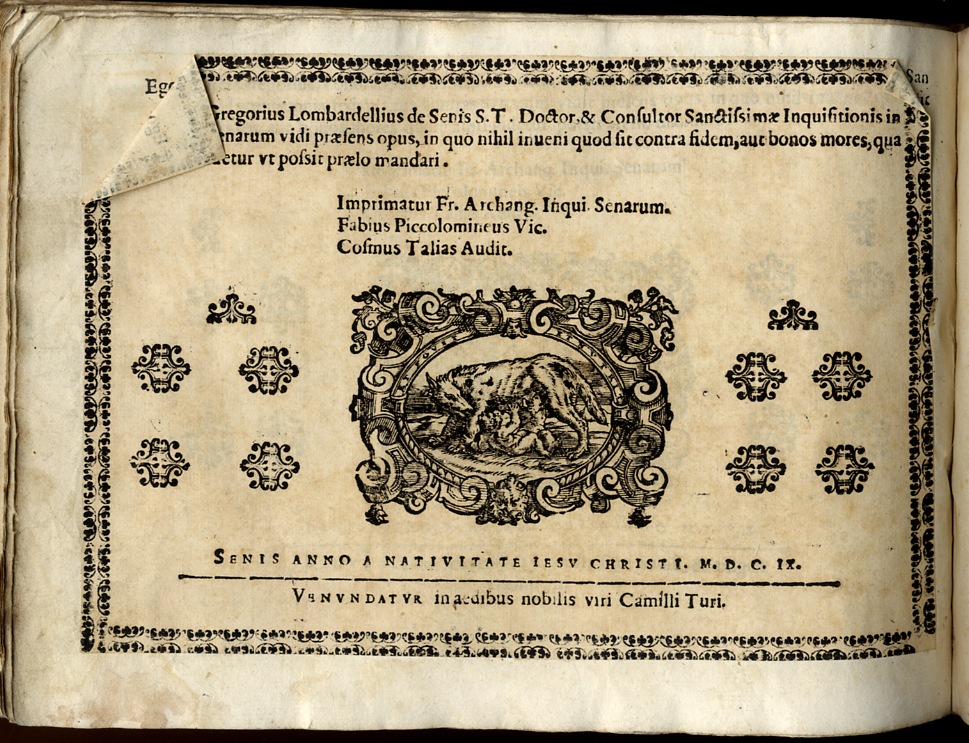

As promised, here is the picture of Guy’s 1610 Capoferro, with the 1609 page stuck over the top of the 1610 page: