AA: Well, hello, sword people, clash, clash, clash. This is Guy Windsor, except it’s not, it’s Ariel Anderssen interviewing Guy Windsor, Dr Guy Windsor, like an amateur because I haven’t listened to your introduction really enough to do it perfectly, but I know the sword people bit is very important. How was that?

GW: That was excellent.

AA: So what are we doing? You interviewed me last month for your podcast, which was very lovely and I really enjoyed talking to you. And you said during the interview, you said which town you lived in. And then the next week I realised I was in your town and I invited you out for lunch and it was a lovely thing and I thought, what an exciting new friendship this is. And then I asked so many questions because I was so excited. I was so nosy that you invited me to interview you. That’s what happened, basically.

GW: Yeah, basically. And it is episode 100 of the podcast, and we have this thing for numbers that have zeros on them. I don’t know why exactly, but you know, episode 100, it’s kind of a big thing. For episode 50, I got my friend Jessica Finley to interview me for the show and I thought, well, hang on. It’s been about a year. Even when I was interviewing you, there was an awful lot of inquisitiveness coming the other way. But also coming from a perspective that is quite different to Jessica’s, for example because Jess is a vastly experienced historical martial arts instructor. And a lot of the listeners on the show are beginners. So it occurred to me that actually the kind of questions you may be likely to ask are probably be closer to the things that some of the beginners might ask. So it just struck me as well. Here’s a naturally inquisitive person. And also a sword beginner. But who’s been on the show before, so people may recognise her, assuming they’re not already massive fans of your work, which wouldn’t surprise me knowing what I know about the sword world.

AA: And I hope that there’s been some cross-pollination that some people have found your podcast through me because I’m sure there are plenty of kinky people who are also interested in swords. It’s just like there are lots of sword people, hopefully, who are also somewhat interested in kinkiness. So I hope there’s a little crossover.

GW: Well, put it this way, I’ve had quite a few very positive messages and practically nothing kind of snarky or negative.

AA: Oh, that’s nice. Nothing furious.

GW: Yeah, yeah. There’s been none of that. Which I was kind of expecting, because this sort of thing often does rear its ugly head. And, you know, looking at the unsubscribers to the newsletter, because I send out something about the podcast in the newsletter. I mean, every time you send out an email to a mailing list, you always lose some subscribers. It’s just normal attrition. And the attrition rate was well within normal bounds. So it wasn’t like, we were making a whole bunch of nasty people very angry by having someone who does sex stuff for work on the show.

AA: That makes me very happy because it feels like probably evidence of social progress. And it also means that probably the people listening to your podcast are, by and large, not massively prejudiced, which is a nice thought. Thank you everyone who is not massively prejudiced.

GW: Actually, funnily, one guy on the discord, he actually comes to my regular morning sessions, so I know him reasonably well through that. And he was like, who would have thought Guy gets a world-famous BDSM model onto the show, and actually the best bit about it for me was the property investment advice.

AA: Oh, that makes me very happy. It makes me very, very happy. Shall I start interviewing you now?

GW: Well, you can if you want.

AA: I feel like the challenge is going to be to keep to the questions I’ve written down, rather than just add a whole lot of supplemental ones. But we’ll see.

GW: We are in no rush. So, you know.

AA: All right. Are you ready?

GW: I am certainly so.

AA: So you are a historical sword fighting instructor. What is like, what’s the best way of saying it? Because that’s not all, is it?

GW: That’s actually a really difficult question, I mean, I changed my job title about six years ago to Consulting Swordsman.

AA: Beautiful. Yeah, that’s beautiful.

GW: My theory was, you know, Sherlock Holmes could be a consulting detective and Moriarty could be a consulting criminal. Why can’t I be a consulting swordsman. It turns out I can.

AA: And it’s good, and it covers the whole range of what you do, right?

GW: Yeah, because, you know, I write books and I produce online courses and I teach in-person classes and I run various things. I also have a few students who I am teaching how to make a living, doing what they want to do.

AA: Like a kind of mentor.

GW: Yeah, yeah, exactly.

AA: So you’re a consulting swordsman, I’m a BDSM model. These two jobs are almost exactly the same thing. And so I’m going to interview you about… They are not almost the same thing,

GW: No, weapons control. Very important.

AA: There are some things that are in common, maybe.

GW: Like informed consent, for example.

AA: Yes, absolutely.

GW: The thing that makes what we’re doing when we’re actually trying to hit each other with swords ethical is the fact that both people know exactly what they’re getting into and have agreed to the details of what they’re going to be doing.

AA: Yes, and are somewhat aware of the risks.

GW: Right. Yes.

AA: All right. So I wrote down some questions about areas of your life that I’m particularly curious about so, let’s get started. The first question is what is your first sword related memory? And did it feel important at the time?

GW: OK. I don’t have a first sword related memory that I can pin down. Blades have always been massively attractive to me.

AA: So do you remember an early experience of finding a blade massively attractive?

GW: You would probably have to ask my parents because it goes back sort of beyond conscious memory, but like, for example, in my stocking, when I must have been, we were living in Argentina, so it must have been the Christmas where I shortly after I turned six years old. In my stocking there was a little pen knife in the shape of a fish. And I opened it to open the other presents with and, of course, cut myself in the process. But I didn’t actually care. I just sat up in bed and bled over everything because I had a knife. And that overwhelmed any sort of, Oh my god, I’ve cut myself because, you know, as a kid who was massively keen on woodwork, for example, I’d cut myself before, it wasn’t like the first time blood had come out of my hands. I was more interested in the knife and the fact that I just cut myself opening it. I think my main concern was if my mum saw that I’d cut myself she might take the knife away.

AA: Which she might well have done, I imagine,

GW: But she didn’t.

AA: Do you remember what you wanted to do with this knife?

GW: Open the presents.

AA: OK. OK, so it wasn’t like you wanted to fight someone to the death with it, you just liked having it.

GW: And it’s a funny thing. For me, martial arts and blades didn’t really overlap until I was in my 20s.

AA: Oh, my goodness, right? I just assumed that it would. All right.

GW: Well, one would assume that it would. But I don’t really know how this sort of division happened. But I started doing karate in various forms when I was about nine, something like that. Pretty much as soon as such things were available.

AA: And did that feel special to you as well?

GW: Oh, totally special. I think the origin of the whole martial arts thing for me was a book, Asterix at the Olympic Games, something like that.

AA: Oh, I remember that, I loved it.

GW: Or The Twelve Tasks of Asterix, something like that. Asterix and Obelix have to do a whole bunch of Olympic challenges, a bit like Hercules’ challenges and one of the ones is get challenged by this little Japanese dude in a judo Gi, who sort of pastes Obelix, picks him up, bashes him against the ground like beating dust out of a carpet. And so, Obelix, even though he is way bigger and stronger is just completely destroyed. But Asterix goes, oh, that’s really impressive. Can you teach me how to do it? And the judo guy is flattered and teaches Asterix how to put him in locks and stuff. And of course, it’s like absolutely standing on his chest and pulling up on his hand, and there’s just knots appears in the man’s arm, it’s kids’ comic books. Yeah, right. And then at the end of it, there he is, with his arms and legs literally in knots and he says “Yes, I am completely immobilised.” Of course, Asterix has now won.

AA: Yes, very cleverly.

GW: Exactly. So what I got out of that was martial arts exist. Small people can beat the living shit out of big people. And my older brother at that time wasn’t terribly nice, so that was very attractive and cleverness is better than strength. So I got totally into the whole martial arts thing at that point. But it took a few years before martial arts became available, because we were living in Argentina at that point. And there wasn’t anything around. We were living near Salta, in a place called Cerrillos, which is just basically a village outside south end of the city. So there wasn’t any martial arts stuff. This was the 70s. And then we moved to Botswana, and eventually we found a karate chap, who was basically, this is Korean guy who was running karate classes for like three or four kids at the golf club in Gaborone in Botswana. So we were doing that for a bit. I always knew I wanted to do swords as well.

AA: But you haven’t found any.

GW: And my mum told me that sword fighting was called fencing, and it’s done like this. And we’d done a little bit because her dad, my grandfather, was a fencer. Interesting bit of historical martial arts trivia. My grandfather fenced with Leon Paul, founder of the Leon Paul Fencing Academy. Leon Paul fenced with Alfred Hutton. Alfred Hutton wrote some of the foundational texts for historical martial arts in the late 19th century and early 20th, things like The Sword in the Centuries. And there’s a lineage that can be traced back from that all the way to Angelo and beyond.

AA: So this probably made you quite happy.

GW: Yeah. When I eventually found it out much later. So anyway, so I managed to get into sport fencing when I was at school. Because when I moved to public school, which was Oakham, they had a fencing club. So I joined that and basically did sport fencing from the age of 13 to 18 school and then carried on at university.

AA: So did that feel somewhat magical to you?

GW: Yeah, it was swords. It felt like swords, because I wasn’t terribly interested in the competitions. I did the competitions because they were a necessary part of the training process. But the electrification stuff I just found really tedious, like putting on all the gear. It’s just annoying. And of course, it encourages all sorts of stuff that wouldn’t work in a real sword fight. But at that point said it felt real because it was the closest thing to real that was available. But in my head fencing was fencing and martial arts was martial arts, and there was no real connection between them, which when you’re comparing sport fencing to, for example, karate, that’s kind of true. They’re trained differently. They’re approached differently. They are just different. So when I got to university. I was doing fencing on Mondays and Wednesdays. Tai Chi on Tuesdays and Thursdays, Kobudo, which is this Japanese weapon stuff on Fridays, karate on Saturdays. And there was usually some kind of martial arts thing on Sunday, too.

AA: So it was like you sort of patchworked together an approximation of what you would eventually be able to do that.

AA: May I ask, if you were 10 years old now I’m growing up in the UK, what would the ideal thing for you to be doing now? Could someone who is a child now come and join your classes or are there classes they could do?

GW: Absolutely. It depends where they are, and I’ve personally never run kids classes specifically. And the youngest person who’s ever successfully joined the regular classes was 10 when he started. But that’s unusual. Most even at 14 are possibly a bit young. But there are plenty of other clubs that do kids classes.

AA: So they wouldn’t have to do what you did, they’d be able to find a closer approximation of what they were into.

GW: Yeah. Although honestly, there is a lot of merit in doing other martial arts, not just the swords. Not least because most historical martial arts instructors are amateurs and have a specific interest in a particular bit of historical martial arts. Maybe they do this early 17th century rapier and associated stuff, or maybe they do medieval stuff, or maybe they do smallsword or whatever. And many of them, and why should they, don’t have a broad base in kicking arts and grappling arts and that sort of thing. So honestly, I would say, for small kids, judo is probably the best starting point, because it teaches them grounding and mechanics and grappling and how to throw. Judo has been developed to teach children these things. And it has a really, really good children’s training programme. And because you’re not punching and kicking, you can start really young and actually really do it safely. And then maybe after a couple years of judo, maybe add taekwondo or some kind of something with kicks and punches. So you learn how to use your hands and feet and any kind of weapons practice at that point, or as early as you can, so you get used to using a tool.

AA: Yes. So actually what you did, what you put together for yourself through your childhood and teenage life, it wasn’t bad, actually. It wasn’t a bad beginning at all. If you were doing it now, you might have the privilege of some more choices, but basically you did put together a kind of training regime for yourself that was fairly sensible.

GW: Yeah. Not that I knew what I was doing. Most of that was just luck.

AA: Well, you gravitated, I guess, towards the stuff that meant something to you, I suppose.

GW: Yeah. But also the stuff that was available. I mean, really, it would have been it would be very useful to me now if I had it some kind of judo or wrestling background when I was a kid.

AA: Because you couldn’t find that at the time.

GW: Yeah. And honestly, I’m instinctively a hitter, not a grabber. Given the choice at the age of 10 between, say, judo and karate, I would have picked karate, because punching and kicking makes more sense to me intuitively than grabbing and throwing. But a complete martial art has all of these things.

AA: Yes, yes. So if you had had the opportunity to add judo into your training, it would have good.

GW: Or jiu jitsu or any of the others or just Greco-Roman wrestling. I mean, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with American collegiate wrestling. Some of those wrestlers are phenomenal. It’s just the rules are a bit different, so it looks a bit different. But I think the fundamental skill set is pretty much the same as it is for judo.

AA: I had sort of assumed you’d have a story about being eight years old and being given a plastic sword, and suddenly your whole world opening up and actually was it was a sort of more gradual thing than that.

GW: Yeah. You reminded me of when we were living in Botswana, my two best friends, the problem with this expat sort of migrant lifestyle. You made friends with kids and then they’d go away somewhere. So my second round of best friends in Botswana, Patrick and Niels used to come around to my house and I’d found these metal poles in the garage and two of them we called naginata, which is like a Japanese glaive, and basically a blade on a stick. And one of them was like shorter, and that was the katana because we were dead into Japanese weapons back then. And we would just fight each other with these things. All afternoon and then after a bit, we got into Dungeons and Dragons. I never really got into Dungeons and Dragons properly because we were like, OK, hang on, you’re supposed to fight this troll or whatever and roll the dice to see what happens. We could do that, or we could outside and one of us could be the troll, and the other one could be the person’s rolling the dice and we could actually have the fight.

AA: I can see why that would be more appealing to you. Did you do each other terrible damage? Were you all right?

GW: I mean, I remember like I sprained my wrist once because Niels was really good at tripping. He was a tenth dan tripper. I mean, tripping as in tripping somebody up. Not as in taking advanced substances. We were like, you know, 11 or something. He was really good at hip throws. One time he got in under my weapon or whatever, and he did a hip throw on me and I put my hand out. I sprained my wrist and so I had to use my katana with one hand.

AA: There is something special, isn’t there, about a fighting related injury or an injury acquired in the pursuit of the thing you love?

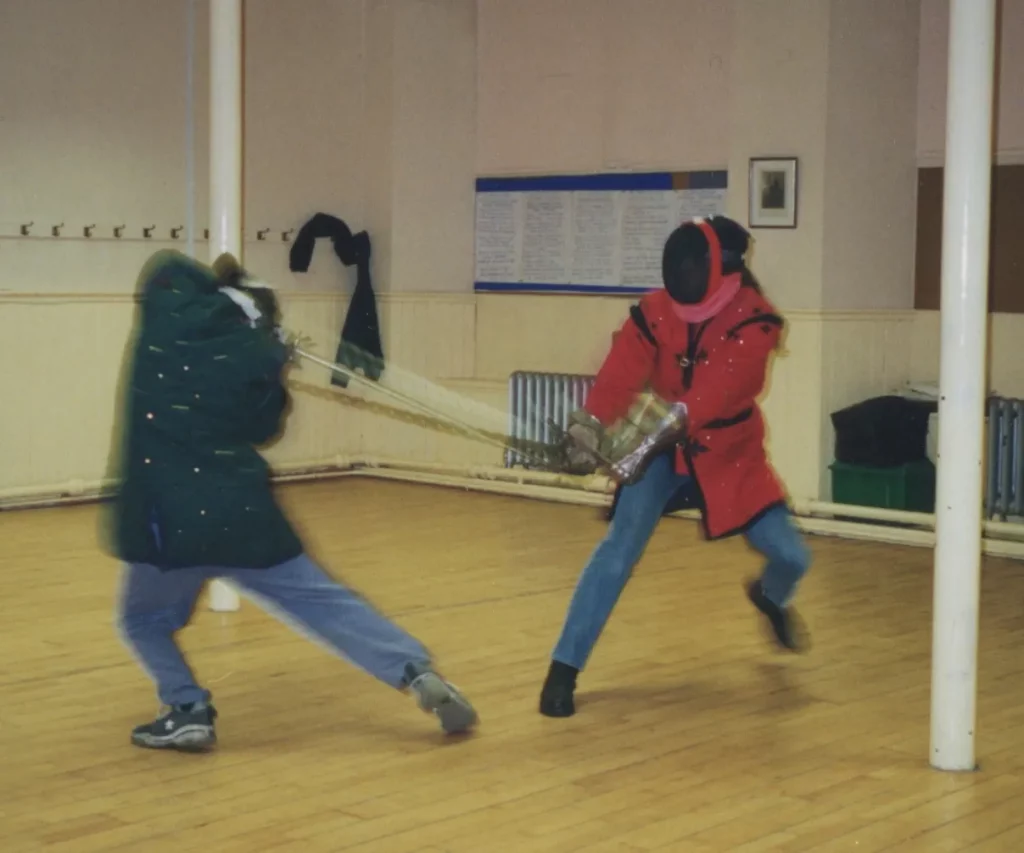

GW: Absolutely. And one of the things that a lot of historical martial arts people do after tournaments is they put up photographs of their bruises. Oh, yeah, like, oh, that was a really good shot from so and so.

AA: Yes, I’ve got a scar on one knuckle from a sword, and oh, I love it. It’s tiny. No one can see it, but oh, I love it.

GW: I have a scar on this finger where it got broken by a longsword.

AA: Oh, that’s a wonderful story.

GW: Well, let the record show this was before I turned professional and I actually had that day, got a pair of steel gauntlets, I’d ordered them from the Czech Republic from what used to be K and K Art is the name of the manufacturer. And they were there and I had them and I just a little bit of bish bash bosh with my friend Paul before we kind of got the session going and he broke my finger because my steel gauntlets were in my fencing bag and not on my hands. Because the stupid runs very deep in some places.

AA: But still, when you say it, it sounds very cool. It doesn’t sound like it was because you didn’t do the basic putting on your safety equipment. It just sounds cool.

GW: Well, I have a scar on my head here. Oh, that was great. When I decided to move to Finland, I challenged everyone in the Dawn Duellists Society to a duel as a kind of like, I want to fight everyone before I go.

AA: This is so romantic.

GW: And in that process, I have a photograph of all the people who I fought that day, and there’s about 12 of them. And the last one, a guy called Kieran, who he was tired for some reason, I think he had a night shift the night before or something like that. And he was not really in a fit condition to fight. And he said so. He said so. I, being a fool, persuaded him to fence me anyway. And we were fencing with longswords, with the standard protection at the time, which was like an ordinary fencing mask and steel gauntlets and a padded gambeson. I threw a sword at his head. Not literally. He got out of the way, and bang, hit me in the head. But he was really tired and he was under some pressure and he did it instinctively, and it caved in the back of my fencing mask and split my scalp. And I had blood pouring down my face. I think it was Rosie, somebody there was taking photographs of it and we actually have a photograph of the moment he hit me. And of course, after photos and a photograph of me like holding my head and blood pouring down my face with everyone else who had fenced me that day, all in the same photo. That was great. And then, it gets better. Obviously, head injury. I couldn’t drive. I had driven to practise and my girlfriend at the time didn’t have a driving licence, so that just stayed where it was. And so my friend Paul drove me to the hospital, right? At the hospital, head injury, straight to front of the queue because they’re careful about these things. And of course, it’s a sword. A whole bunch of like student doctors who start coming to see an actual sword injury. And as it was, it was just a split scalp and three staples out the staple gun and a card saying, if you find this person, bring him straight to the hospital or whatever. So like, if you start to get dizzy, you can wave it at a taxi and they’ll take you to the hospital. They take these things very seriously. In the hospital, we weren’t there for very long. Then we thought, okay, I can’t drive, so we might as well go to the pub.

AA: Surely, that’s not the best thing to do.

GW: It was fine. When we’re outside the pub I was like, hang on, Paul, this is a perfect opportunity for a wind up. So I waited at the car with my girlfriend, and Paul went in. And there was Kieran, nursing a pint feeling terribly guilty and worried, and a few of the other guys were there and Paul was like, well, I took him to hospital, and when we got there, he just sort of collapsed on the floor and Rosie stayed with him. The doctors say we’ll know more tomorrow. So, of course, Kieran turns white

AA: Poor Kieran!

GW: Then I march in, all smiley, and go, “Kieran! You owe me a pint!” “You fucker!” He had felt totally guilty. And as soon as we played the prank on him, he just felt totally much better. because the slate was more than clear. And in fact, he owed us another smack in the head.

AA: That is probably actually a very good way to handle it. But what an amazing injury to have. I mean, I’m sure it wasn’t great at the time, but it’s quite cool now.

GW: Honestly, the finger was much worse. With the finger, I actually went into shock. I had to lie down with my feet up and everything. Broken bones can do that sometimes.

AA: I didn’t know that. I’ve broken fingers.

GW: It wasn’t like, you know, the shock you get from, like bleeding out. But I went all woozy. Fortunately, I knew first aid, so I just lay down the floor and put my feet up on something and I said, yeah, okay, if I just lie here for a bit.

AA: These are proper sword injuries.

GW: We should probably flag up. It is actually not cool to get injured.

AA: I’m sure you’re right.

GW: And these cases of me getting injured were entirely due to me being thoroughly stupid in the moment.

AA: That is a very professional thing to say. Well done.

GW: But it’s true. And there have been no such injuries since.

AA: which is obviously good. You’re very responsible, but still very cool to have a sword injury to your head. It just feels like the sort of thing that should happen to someone who’s lived the life that you have.

GW: It’s literally a duelling scar. Which is cool, but wrong. Very wrong and bad.

AA: Let’s move on. When you were interviewing me, we got into a conversation that I really enjoyed where we were talking about some of the sword fighting that we’ve seen on television and film and stuff that impressed us and stuff that didn’t impress us. And afterwards, I found myself wondering what is the best sword fighting you’ve ever seen? Was it in real life? Was it on camera or was it in your head? So I thought I would like to ask you the story of that if there is something that comes to your mind.

GW: OK. Some sword fights have done well on screen. Something like the really stylised Chinese stuff like in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, that sort of movie, that’s an art form of its own. It doesn’t look like a real sword fight, necessarily, but these are extremely highly trained performers doing art at an extraordinary level. And it looks amazing and it’s wonderful, but it’s not really a sword fight. We have sort of similar examples in some other movie franchises. And generally speaking, in most of Western movies, the closer is the sport fencing, the more accurate it’s likely to be, because that is the primary training of most of the fight directors. So, for example, the smallsword fight at the beginning of The Duellists, Ridley Scott movie, are epic, and all the fights in that movie are fantastic. Napoleonic era smallswords and sabres are reasonably close to what people like Bill Hobbs, who was the fight director, actually know. I have seen some absolutely stunningly good sword fighting in various disciplines in, for example, demonstrations done by historical fencing groups. And often it’s not scripted, so it’s not choreographed. What it is, is they will have agreed an end point and agreed a start point. And they will start with the agreed start. And then they will just fence with this sort of keeping things in the pocket as it were. So they’re not going to accidentally hit each other and then one of them will give a signal and then they will go into the end move and there’s the kill.

AA: That’s a very interesting way to do it.

GW: Actually I was chatting with Ben Crystal about this on the podcast last year, and we sort of felt that that’s probably how they used to do it in Shakespearean times.

AA: Rather than choreographing the whole thing.

GW: Yeah, because they didn’t have time to choreograph. I mean, they barely rehearsed.

AA: Yes, that’s true. So they can’t have done.

GW: Like the Princess Bride fight. If you read As You Wish by Cary Elwes.

AA: I did. I mean, so much rehearsal. So I mean training.

GW: They trained and trained and trained for hours and hours and hours and hours spread out over weeks and weeks and weeks to get that fight as good as it was and it totally paid off. It is a totally awesome fight. But it is not by any stretch of the imagination realistic. It’s just awesome. It has the same sort of awesomeness as like House of Flying Daggers fights or Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon fights. It’s art.

AA: But no, you’re right. Of course, originally there wouldn’t have been anywhere near the time to put choreography together.

GW: I’ve been in some absolutely epic sword fights. The one that just immediately leaps to mind, not least because I’m interviewing him in a couple of weeks, was in 2006 with Christian Tobler. First time we ever fenced each other. Christian Tobler, for the absolute newbies out there, he’s like the godfather of German medieval martial arts. His book that came out in 2002 called Secrets of German Longsword was the first English language source of medieval German longsword material available to the English speaking community. I mean, obviously 20 years ago. So the interpretation and academic stuff has moved on with the 20 years of development. But still as a resource, my God, he’s like the reason most people who do longsword in the English speaking world are doing German longsword, not Italian.

AA: OK. That sounds quite pressurising.

GW: No. What do you mean? Well, he was he was there at this event. It was in Dallas in 2006 and we were like, oh, we should go fence each other. So we found a quiet spot. It was done in this sports venue and they had these squash courts. So we just went to one of the squash courts and closed the door and started fencing each other. It was gorgeous. It was like a conversation. An earnest discussion between old friends.

AA: I understand that.

GW: It was absolutely fantastic. We were ten hits into it, and then we realised that there was just like a crowd of people watching through the glass doors. “Guy and Christian are fighting, Oh my God!”

AA: Did it matter to you who won or does no one win in these sorts of things?

GW: When I got home, I talked to my students about it. One of them said, “Who won?” And I was baffled by the question. I thought about it for a minute. I was like, we did.

AA: Yeah, yeah. Because it’s collaborative, I guess, a little bit like BDSM. It actually might look like one person gets the better of the situation, but actually it’s a collaboration.

GW: I certainly had bruises from it and so did he.

AA: And so everyone wins, like a conversation.

GW: I don’t remember what the first hit or the last.

AA: Obviously everything I do in my field is recorded everything and I guess a lot of the stuff in yours is not recorded. It does not make you sad, ever, because you don’t have a record of what happened?

GW: No, it doesn’t make me sad because, actually, one person videoed it without asking us, and I told them to delete the video. And they did. Because it was done without permission. You know? I am not a fan of recording everything. I’m really not.

AA: That’s why our Twitter profiles are so different from one another.

GW: Well, yes, that’s fair. Also, I am never naked on my Twitter profile. Ever.

AA: No, that’s what I’ve noticed.

GW: Sorry. For example, I teach this class, my trainalong. Three mornings a week. And I recorded a bunch of them from my solo training course. And every now and then when we’re covering something that I want a recording of, specifically, I’ll hit the record button. But generally it’s like the difference between going to a live gig and listening to recorded music.

AA: Yes, I totally understand that.

GW: And yeah, people usually record live gigs these days, but they don’t record all of them.

AA: And it might not be the best way to experience it.

GW: Sure. And the thing is, I’ve been doing this a really long time, if everything I ever did was recorded, I would have terabytes of video files, which I would then have to somehow organise. But it’s funny you say that, because what that brings to mind is, but one of the ways that I can track what I’ve done is to look at what I’ve published. So what happened in 2018? These two books came out. What happened in 2019? This book came out. So when looking back, I can go, well, I definitely did something last year because here’s a book. Yes. Sometimes it’s an online course, but usually it is a book. And that serves a sort of similar, ‘this is where I’ve been’ function.

AA: Yes. But like some individual things that you’ve done that you’ve loved, they live in your memory.

GW: Yeah. I have kids, and so I have an infinite number of pictures of my children when they were little, and some of them are just appallingly cute. And there’s been a lot of them over the last 15 years. Yet, I don’t spend much time looking at pictures of the children when they were little. I mean, it’s a guaranteed kind of, oh, aren’t they lovely sort of moment. But right now the children are lovely. And we’re actually in the process of actually doing things together, like I mentioned before we started recording, I took my daughter for a flying lesson for her birthday. And yeah, I’ve got a couple of pictures of them. I didn’t record the whole thing.

AA: No, no, because I mean, obviously it does take you out of the moment. And it’s interesting to see that our different attitudes to how much we record of our lives is reflected in our jobs because a lot of what you achieve is in real life. It’s live, isn’t it? It’s teaching, that lives in your memory and it lives in your students. But you don’t have recordings of all of it.

GW: Yeah, but then I have books and what have you, which are based on what I’ve learnt doing those things. So we have the edited highlights recreated for the purposes of expressing a particular idea.

AA: Yes. Which makes all the sense in the world. And so it’s a lovely thing to hear that actually the best sword fighting you could recollect was something you were in and you don’t have a record of it. But it lives in your mind. That’s awesome. I was very interested when we talked before about how your career emerged. I was very interested in your story about your PhD and what you were writing, and I wondered if there was a sort of a particular point at which you realised that this is something you could do for an actual full time job because it sounds like it might have emerged for you quite slowly, that realization?

GW: Oh, yeah, there’s a story to that. I have to edit it slightly because many of the people involved are still alive. But in my usual angsty stressy way, I was living in Edinburgh and things got to a point where I thought I was going to either stay in Edinburgh and have no children or move to America with somebody else and have kids. And I did not know what to do. I was conflicted in all sorts of ways. And so I thought, hang on, I’m a martial artist. At this point, I was self employed as a cabinet maker in Edinburgh, doing some antique restoration jobs, mostly making no money at all and not particularly happy in it. I was teaching at the Dawn Duellists Society on Wednesdays, and we’d usually get together on Sunday as well, and do bish bash bosh, which was the highlight of my week. And I’d been doing this shamanic meditation training with this person who was actually the person I might move to America with. It all gets very tricky.

AA: Because you were young, right, and that’s what happens when you are young.

GW: I wasn’t that young, I was 27 at this point, 26. And so I thought, what the hell do I do? And so I thought, well, OK, martial artists, in most martial arts origin stories there is a bloke goes out into the wilderness, he usually goes up the mountain, sits on top of the mountain and meditates, and then the way becomes clear. Like Musashi, probably apocryphally, famously wrote his Book of Five Rings in a cave in a mountain. I may be misremembering, but there are certainly stories like that throughout the martial arts canon.

AA: I’m hoping this is going to lead to you going up Arthur’s Seat. Is that what is called?

GW: There is a bit of Arthur’s Seat later. So I said to my friend Paul, I am going. I need to go up into the Highlands to meditate. He was like, OK. And so we got in the car and we went up because he came from a village called Glenuig, near Fort William. And so we went there and there was a handy mountain next to the village, not a very big mountain. Parked at the bottom, set up the tent. And I walked up to the hill. I sat on the hill. And literally within seconds, if I have a talent for anything, it is altered state of consciousness, I can flip in and out of them really easily.

AA: Oh, wonderful, you really should do my job, that’s very helpful.

GW: Well, maybe, you’d have to talk to my wife about that. I’m not sure she’d approve. So anyway, I get into the state. it’s just there. Close your eyes, it’s there. And his voice absolutely clearly in my head said, go to Helsinki and open a school of swordsmanship.

AA: Oh, my goodness. But that’s so specific.

GW: It was absolutely specific. It could not be clearer. I literally have not considered teaching swordsmanship for a living beforehand.

AA: That is quite a moment.

GW: It did not occur to me that this was something that I could do like full time profession. I mean, I taught individual lessons for like 10 quid an hour or something. I’d made a bit of money here and there, but nothing like a living wage. And so it had not occurred to me that you could teach historical swordsmanship for a living at all, right until the voice said, go do that. So I came down the hill, and Paul was like, that was quick. I said, I’m going to go to Helsinki and open a school of swordsmanship. And then we stayed the night in Glenuig and then back to Edinburgh.

AA: I didn’t expect you to have like such a clear moment of revelation.

GW: Yes. It was remarkable.

AA: And why? I mean, did you have any connection to Helsinki at this point?

GW: When I was at university, I did a year out, sort of an exchange year. My third year at university, I did that in Helsinki, and that’s where I met my girlfriend, who I was living in Edinburgh with. It wasn’t somewhere I’d never been heard of. And it also just so happened my three best friends in Helsinki at the time, because my girlfriend was Finnish, we’d go back and forth fairly regularly. The best martial artist that I’d ever met. Best sword maker I’d ever met and best shooter I had ever met. So I figured, well, OK, the school may succeed or fail. But while I’m there, I’m going to learn a bunch of martial arts. Hang out with at least one really high level sword person in the making side, not the doing side. And learn to shoot. So worst case scenario, I pick up a bunch of cool skills and have an interesting time.

AA: Yes. Right.

GW: Oh, I’d lose the money that I borrowed to start the school. But money comes, money goes. And I’m in the extraordinary lucky position that my parents and my siblings and my cousins and what have you, they will not let me starve. And we have like a state dole and unemployment benefit. There are all sorts of safety nets in place for everyone in the UK and in Finland. And yes, those safety nets aren’t great in many cases for many people, but also on top of that, my extended family, we have resources.

AA: There must have been moments since that revelation, there must have been moments when you wondered if it was the right thing to be doing?

GW: No.

AA: Oh, that’s fabulous. So you found exactly the right thing to be doing, basically.

GW: Yeah, it was like flicking a switch. That was in August 2000 I went up the mountain. March 17th 2001 is when I opened the school. We took the car and drove to Newcastle to put it on the ferry to go to Gothenburg, Sweden and put the car on the ferry from Sweden to Helsinki and arrived in Helsinki on the Thursday. It’s two nights or something. Anyway. So we arrived in Helsinki on the Thursday and through my girlfriend and through other friends, we’d already found a couple of places to run classes. One of them was in a little, not sure what they even use it for, like a small sports room in the Olympic Stadium in Helsinki. And that’s where we had the first class. Freezing, snow on the ground, March in Helsinki and the room would comfortably fit a class for about 10 people at about six or seven people have emailed me telling me they were interested and they were going to come. And about 70 people showed up.

AA: Oh, my goodness. What did you do with them?

GW: Well, instead of instead of teaching a class, I did a sort of demo of things for about half the time and I said, well, look, there are way more people present. So then we did a bunch of like mechanics and footwork stuff. If I remember rightly, I arranged things so that people could at least pick up and have a feel of the swords. I had this enormous two handed sword because of course, I was absolutely terrified. Firstly, way too many people. And this is super important, if I fuck this up, the dream dies. And the thing is, if you’re holding a five foot long sword. It’s like a security blanket, or a teddy bear. Because actually, it’s a bit more practical than a teddy bear. So I picked up this sword and stood there and waited and it all went quiet. And I just started talking. And haven’t stopped talking since.

AA: This is a lovely, lovely, lovely start. But what a strange, sudden beginning. Obviously, all the training that you’ve done up to that point was leading up to it. But the sort of epiphany of that’s what you needed to do.

GW: Yeah. I thought I had, Option A Option B. And what was presented to me was like Option X.

AA: Yeah. And it was the right one.

GW: Yeah, no question. It was the right one. This is the one thing where all of the things I do are useful, and the various aspects of my nature. I can’t help but explain stuff. It annoys my children no end.

AA: But very helpful for what you’ve got into.

GW: Even stuff like the woodworking thing as well, when you rent a salle, there’s a bunch of stuff to do to kind of make it look like a training facility. Like building sword racks, that stuff was all easy. Just all sorts of things just sort of came together as like, well, this is obviously why I need to be doing.

AA: That is fantastic. And so this led onto you eventually writing books. This is what I want to talk about next because I know we’ve both written books, but you’ve written more than me and they’re published and everything and you’ve self-published, you’ve traditionally published, and so you’ve got a great deal more experience than me, and I’d love to hear about your process. How do you go about writing a book? How many times have you done this? How many books have you actually got?

GW: It depends how you count. Some books, which are technically separate volumes and published as separate volumes on various book buying websites are also compiled into bigger books with extra stuff. So, for example, I have a series called The Swordsman’s Quick Guides and the seven volumes of The Swordsman’s Quick Guides make up about half of my book, The Theory and Practise of Historical Martial Arts. So just taking like what I consider stuff that I’ve bothered to get myself a hardback copy of, I think there’s 11.

AA: OK, so that’s a lot, which means that presumably you have figured out a process that works for you in doing this. So please tell me about your process. How do you do this?

GW: OK, well, firstly, these days, I do set out to write a book. But that’s a terrible place for most people to start, unless you’ve done it a few times, because a book is big and complicated, and it’s very difficult to hold it in your head at once. So what I tend to do is I set out to write a chapter or an outline, or a list of chapter headings or a paragraph. And quite often it’ll be like, oh, hang on, I’ve covered this already, and some student has sent me a question some years ago and I’ve written a blog post because when an e-mail question is sufficiently interesting and requires a sufficiently in-depth answer, and I actually want to do it then I write a blog post and stick that up. And then the person who asked the question is happy because they get a really good answer, and it’s also useful for other people. So sometimes I can just take stuff I’ve already written and copy and paste it in and edit it into a more bookish format and connect it to the other pieces. Sometimes, if I’m stuck. I will conjure up an imaginary student and teach them the thing like, I’m writing them an email. The thing is, I don’t have just one process, it kind of varies from book to book because they’re all different.

AA: And I guess your reasons for writing them is different each time.

GW: For the Theory and Practice of Historical Martial Arts, I actually set out to do a complete overview of the processes involved in going from ‘here’s this old book’ to ‘I can fight with a sword’.

AA: So this is a pretty massive project.

GW: It took a long time. For me, the hardest part was structuring it. Because getting all of those many, many pieces in place, because of course, when you actually do the thing, you don’t do all the research and do all the physical preparation and then do all the physical interpretation and then all the testing of that. And then you’re done. That’s not how it works. You get into a bit of research and go, oh, that’s cool. I’m going to try this out. And then you realise that actually, you can’t try that out because your hips aren’t flexible enough, so you work on that for a bit while you get into the next bit of research and then you get this technique. Isn’t that cool? Then you test that against this and then you have this whole bunch of techniques which you sort of figured out. But do they actually fit together as a system? Not sure yet. OK, so you go back and it’s just this is this endless sort of kaleidoscopic cycling of things.

AA: Structuring this…

GW: How do you unpin it and put it into this sort of fixed mechanical order that you get in a book? That was hard. But other books, my Advanced Longsword, for example, it was hard until I realised actually we have the advanced longsword syllabus encapsulated in a form called the syllabus form. And so I took each step of the form and expanded it into a chapter of the book.

AA: Oh, fantastic, yeah. Well, how nice to have your structure kind of already done.

GW: I wrote the book in about five weeks, because that’s as fast as I could type it. It was easy once I figured out the structure.

AA: Yes. So I guess because you’ve got this career that involves multiple aspects, you can’t ever stop doing everything else in order to just write, can you?

GW: Yeah, that would be a disaster, because after a week, my forearms would swell up and the tendonitis and my back would hurt too much. And it would just be a disaster.

AA: I’d love to be able to go. You hear about authors booking a cottage by the sea and going off to write. That appeals to me massively. So that actually wouldn’t work for you.

GW: Well, that tends to work for fiction writers who kind of need to separate themselves. Well, some of them need to separate themselves from the real world because they need to immerse themselves completely in the fictional world they’re creating. Or the real world intrudes.

AA: That is not what you need to do.

GW: No. But. It’s funny, I mean, the single biggest barrier to me getting the next book done is email.

AA: Yeah. Just because there’s so much of it.

GW: Right, right. Yeah. And so I have some I have some rules in place for that which I find helpful. I sometimes dream about like a week away to just immerse myself in the book. It would be nice, but we both know that if I have a week away, I probably wouldn’t get any work done at all. If there was no internet connection, I might get some work done.

AA: Yeah, I think that might be the actual the critical part of it. I find myself very curious because your job involves these sort of multiple activities. I’d like to know what is a typical day, what does a typical day look like for you?

GW: OK. It sort of depends. A typical week is probably better than a typical day. Because I have different days, for different things like Monday, Wednesday, Friday, I’m teaching my, I’m not really teaching a class, but in my head I’m teaching a class, which means it’s absolutely sacrosanct. Nothing gets in the way. So I’m doing my so physical, necessary physical training stuff, Monday, Wednesday, Friday. I should do it more often, but this I can square away.

AA: So everything else fits around those fixed points, then.

GW: Yeah, pretty much. And then Thursdays, I generally speaking, I have nothing in my calendar on Thursdays at all. I will get up on Thursdays and I will do whatever. Usually that involves actually really productive work on one of the bigger projects.

AA: So if you were writing a book at that point, would that happen on a Thursday?

GW: A lot of the book is just getting the stuff in your head and typing it out, and that’s just typing. It’s not the thing. That’s just that is the bit that looks like writing. The real stuff is when you’re figuring it out. That’s the really hard bit. And so that will often happen on Thursday. But also, I’m currently building a display cabinet for my beautiful old fencing treatises. And that also counts as a major project because I don’t really distinguish between projects as to whether they are work or not work, like moneymaking stuff or not moneymaking stuff.

AA: Oh, that’s probably very healthy of you. I do, and I don’t think it’s very good

GW: That also frees me up to do projects that aren’t going to make any money but are worthwhile, like podcasts, for example. So far, the podcast is net negative. It actually costs me money to produce it. And that doesn’t matter because been hugely positive in all sorts of other ways. So fortunately, the other projects, like online courses and books make enough money that it doesn’t actually matter that the podcast costs money.

AA: So do podcasts tend to happen on Thursdays as well?

GW: No, I stay the hell away from the podcast on Thursdays. With the podcast, what I do with it is I find the people to interview, I interview them. I do the editing on that. And everything apart from the interview itself is tactical. It is a small action that needs to be done, so this larger thing can occur. Fundamentally the only thing that needs to be me doing it is the interview and to some extent, I think it’s a bit of a dick move to get assistants to contact potential guests. It’s rude. I do that myself because it’s the right thing to do, but really, in terms of like the technical skills required that could be done by somebody else.

AA: But there’s a tension isn’t there between doing things the way you want and the most ethical way and being efficient.

GW: yeah. So on Mondays, I do my class and breakfast and stuff, and then I have like an hour or so what I normally do, is either a bit of writing or emailing stuff. So business stuff. Then I usually go climbing at lunch time with my friends, Katie and Ross. Because social attraction and different physical exercise hits all sorts of important points. It’s indoor climbing, bouldering. Monday afternoons, afternoons are a bit useless for me because I’m usually tired by that point.

AA: So is that when you do email quite often?

GW: Sometimes emails, sometimes have a nap. Then I’m usually cooking dinner in the evening from like five to six. Then we have dinner earlier and then it’s like sort of family time and hangout time or whatever. And I don’t usually work in the evenings if I can avoid it.

AA: Where does your own personal training fit into that.

GW: Oh, I do that Monday, Wednesday, Friday in those one hour slots, but I also do it when I feel like it in any other slot.

AA: I don’t know at this point how important it is that you should carry on training by yourself, increasing your skill level, I don’t know if you’ve got to a point where you’ve kind of plateaued anyway.

GW: Right now, I’m not working on my skill level in terms of weapons manipulation and stuff. I’m maintaining it where it is. So I’m doing the necessary maintenance to keep it where it needs to be. I’m more concerned at this stage with the effects of ageing, I’m 48, and so I’m more concerned with things like hip flexibility and strength and keeping my forearms in good condition and all that sort of stuff. So that’s where I spend most of my training time because the limiting factor on what I want to do at the moment is not weapons skill.

AA: It’s what might be happening to your body as it ages.

GW: But there will come a point where I find neglect weapons stuff for too long, it will start to slip and maybe not be sufficient for what I need to be able to do, which is give a proper professional level individual class. The most technically difficult thing of all in terms of like using a sword is giving a professional level individual lesson. Because what you have to do is you have to adjust the level of intensity so the student is working at their optimal rate of failure. But you also have to be paying attention to what they’re doing so if they do the thing they’re supposed to do they hit you and don’t get hit. And if they do the wrong thing, they don’t hit you and get hit. Which is a super hard thing to do at speed with a high level student. So that’s the skill level I need with my weapons.

AA: Yes. Does teaching, some extent at least, keep you at that level technically?

GW: During lockdown I’ve taught hardly any classes. That’s one of the reasons why I invented my trainalong sessions. Yeah. Although because the trainalongs happen in my study, there’s not a lot of room for weapons. The weapon stuff mostly happens outside as though it happens less often than perhaps it should. But then normally Tuesday morning is podcast stuff. Basically, getting the draft of next week’s ready to send to the person so they can check it if they want to, the guest, making sure that this week’s is ready to go. And of course, Katie will be doing the transcriptions on this week’s episode because she gets sent it at the same time as the guest. So she’s got like 10 days or so to get the transcription done before we launch on Friday. So I try and get everything for this week’s podcast done Tuesday morning and then Katie does the show notes and the rest. And then for the rest of Tuesday, I’m possibly writing a book, possibly reading a book. There’s lots of research and stuff. I’m quite often in my shed doing woodwork stuff. Also, doing the woodwork stuff is when I listen to podcasts the most and the podcasts I find the most useful for my strategic goals they tend to be fairly technical and so I have them on when I’m doing woodwork or what have you. I can’t have them on what I’m doing, anything involving writing or the emails, because it’s language right? And they are completely useless to train to. They don’t have the same kind of, you know, get the motor running feeling as listening to The Eye of the Tiger when doing sword forms.

AA: Totally, totally. I love it that your woodwork sounds like my sewing. And exactly, when I’m doing dressmaking, I’m listening to my podcasts. Exactly. It’s like it frees up that part of your brain and you can do those two activities in a very kind of nice, comfortable way together.

GW: And on Tuesday afternoons is when the weather allows, may not allow today, it’s looking very overcast, I have a flying lesson. And then Wednesday morning, is a bit like Monday morning. I don’t go climbing, but I usually Wednesday afternoons I have a meeting with a guy who does my Facebook ads for me. That’s just a short one. And I have a longstanding hour long chat with an old friend. Pretty much every week.

AA: You’ve done a great job of prioritising stuff to make you happy, to kind of pour happiness into you, to recharge your batteries.

GW: The thing is, for most people, I think, the biggest challenge of the pandemic has been mental health.

Thanks to medical stuff and vaccines and all that sort of thing most people are not in mortal danger. Which is fabulous. But there are all sorts of worries and stresses and strains. And also for a lot of people, I mean, we’ve been super lucky that I happen to have stuff that people want to buy during a pandemic, like online courses and books.

AA: Thank god. Well done for setting things up that way.

GW: I can’t take any credit for it. That was luck. I didn’t deliberately build my business to be pandemic proof. It just happened to turn out that way.

AA: No, but you did diversify enough as it happened that it was somewhat pandemic-proof.

GW: Wherever possible, I prioritise passive income producing stuff. Yeah, because I’m pretty much the sole breadwinner in the family and my children’s quality of standard of living depends on my income. So I can’t fuck around with it. I see that as another kind of a moment, it must have been 10 years ago, something like that, where like in the build up to me going up the hill and finding out I should be teaching, I’d had a run of nightmares, like for weeks. I’d wake up with nightmares every night. And that’s not any specific nightmare I can remember, but it was just nightmares. And as soon as I’ve made the decision to go to Helsinki and open the school, the nightmares stopped. So I always say it was my subconscious basically hammering on the back of my head going Guy, you need to be paying attention to something. This is how we’re choosing to tell you. Everyone gets nightmares occasionally, but this was like night after night. And the same thing happened, the same series of lots and lots and lots and lots of broken for sleep nightmares for several weeks. I was like, what the hell is going on because I recognised it from previous time, which was more than 10 years before, but it was like, OK, this is the same thing. And so what is it? What needs to change? What I figured out was I’d let my sort of artistic disdain for money, and which, of course, one can afford that when you have a comfortable middle-class background and you know your children won’t starve, because your siblings are making plenty of money and they’re nice people, and so would not let the children starve. I recognise it for what it is, but it was like, oh, you know, I don’t really care about money. I wasn’t really paying attention to the money. And I realised, like, for example, my weekend seminar fee. I set it in 2001 at a thousand euros for the weekend, plus travel expenses, what have you. It was still a thousand euros for the weekend, 10 years later. So it was effectively about 700, with the inflation, all that sort of stuff, even though I was getting much better at my job during that time. Of course, it was nuts. It was absolutely insane. So I realised I was not basically taking care of business, and my children’s standard of living was going to suffer because of it. And that was an untenable position because it basically put my sort of ideas of how you’re supposed to be as an artistic person, martial artist in this case, against my idea of how you’re supposed to be as a parent where you put the children first. And that was causing the stress, it was causing the nightmares. So what was I going to do? And so I put my prices up for a start. And then I thought, well, hang on. Books and writing and stuff. Maybe I should do this, maybe I should do that, and I just started to put together like. Well, lots of things came together at the same time. So it’s hard to say what came first and how it all worked. I started self-publishing as well as traditional publishing. I did some crowdfunding for various projects that started around that time, I forget exactly when, but the upshot was that in 2016, 2015, we had enough money coming in from my books that we could move to the UK. So we were not dependent on me showing up and teaching. And then in 2016, alleluia, thanks to Joanna Penn, who is fantastic. And I started doing online courses and oh my god, they are so much more lucrative the books.

AA: OK. Oh, what a lovely discovery to make, because I guess you didn’t know that.

GW: I had no idea. No, I had no idea. Producing an online course is much faster than writing a book, and costs less and makes way more money. I’m still producing books because, yeah, the books are a necessary part of me figuring out the whole historical martial arts thing. And some students need books and other people like courses because people learn differently. But yeah, I mean, they’ve been fantastically helpful in basically funding my mental health through the pandemic.

AA: Yes. And I’m glad that it has meant that when you describe your working week to me, there’s quite a lot in that working week that isn’t work, which just seems really healthy.

GW: But then I think it’s a really common mistake that people make when they’re looking at somebody who’s writing books or doing that sort of thing. Is they confuse typing for writing. And, you know, time spent reading a book is just as useful as time spent typing out your own.

AA: Yeah, yeah. I often think that actually, the writing I’m doing, it happens really when I’m walking. So I understand that. So you have set up your life so that you’re not under this ridiculous pressure to be constantly exactly doing stuff that generates money now. And that just sounds like it sounds like you’ve just balanced things very well at this point, I’m sure it’s been hard to get there.

GW: I try. And yeah, I have a fundamental rule that if a friend needs to talk to me then that takes priority over anything other than my wife or children needing to talk to me. So I actually have four or five regular or semi-regular meet ups with friends. In the course of a given month there will probably be 10 or 15 of these where we basically sit and hang out and chat. It is over Zoom because, you know, these are people in like Oregon and Wisconsin and Melbourne, Australia, you know, they’re all over the place. And normally in normal times, I would travel a lot and I would see them then and now we’re doing this actually much more regularly over Zoom.

AA: Yeah, it’s been something that’s happened, isn’t it? Yeah, we do it more regularly. It’s maybe not quite as powerful, but you do it more.

GW: And it’s vastly better than nothing. That also means that when stuff happens, like when a bad thing happens, there’ll be somebody, I’ll also talk about it with my wife, possibly not with the children, it depends what it is. But then it’s not a stretch to just meet up with somebody else because there are these regularly scheduled and sometimes we just go online and play a board game or something on the internet and chit chat. And sometimes we have deep conversations about meaningful stuff and sometimes not really much happens.

AA: Yeah, friendship is magic isn’t it.

GW: Exactly. Yeah.

AA: Do you manage to take weekends off work?

GW: Usually what I’m teaching a seminar it’s at the weekend. But other than that, again, because most of what I do, I don’t file in my head under “work” unless it’s a useful thing to do to get it done, then, I’ll sometimes do a bit of work in the weekends, like answer a few emails or I’m if I’m deep into writing a book, I may very well be up early because the book will wake me up and I will just go downstairs and put a thousand words into it. And then one of the kids comes down and puts the TV on and that’s like, OK, fine, I’ll go get some coffee now. Or take my wife a cup of tea or something. It’s because I don’t really have these very strict distinctions between work and not work.

AA: Yeah, that’s very interesting. I don’t think I’ve met someone who’s kind of described things that way before, and it’s an interesting difference from the way a lot of us approach things.

GW: Well, I have a pretty clear idea of my long term strategic goals. And to accomplish those, I have to be mentally and physically fit to do the necessary things. And so in my head, you know, a while ago, I needed to go see a therapist for emotional childhood stuff. And so I did. I did that in the middle of the working day because that’s convenient for us both. And it totally counted.

AA: Yeah, totally. Because what you could have done is prioritise making another $100. But actually, in the long term, what’s going to make you able to carry on doing your job is having decent mental health.

GW: Exactly. Yeah. So we’re halfway through the week. Thursday, is clear. Thursday this week, I’m assuming, if the weather is up for it, I’m going for a nice long walk with a friend and we may talk about work stuff or we may not.

AA: Thursday is the day where you can kind of make it up.

GW: And usually that’s the most productive day of the week by a mile. Because I don’t have to hold any bit of myself in reserve for a commitment later in the day.

AA: Yes, I entirely understand that. Right.

GW: It used to be when I was teaching, I used to be teaching Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and then sometimes the weekends. And then one of the students took over Fridays, I think, so I was teaching Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday. That class starts at six o’clock, my whole day was structured around six o’clock, I need to be on my top form.

AA: Yeah, it’s quite an inhibiting factor, I think.

GW: So I didn’t have those days off. No, they were not “off” in any meaningful sense, because I have to be on at my maximum capacity at six o’clock.

AA: So everything leads up to that.

GW: Yes, exactly. So on Thursdays, there is nothing I need to be awake for. So if I completely evacuate my brain in the morning doing like really kind of deep focused, intense stuff, I just sleep it off in the afternoon. And if I’m dozy in the evening, it doesn’t matter either.

AA: No, good to have one of those days. And then on Friday, you teach again.

GW: Yeah, Friday I’ve got the morning session and then there’s, some type of like general kind admin stuff. Maybe some creative stuff and sometimes I’ll go climbing with Ross and Katie, sometimes not. It kind of depends. After I usually have another one of my friends meetings at three, and a Friday evening, it’s kind of the start of the weekend. I mean, OK. Both my brother and my sister are very hard working in the classic sense and they are just appalled and baffled by how little I appear to work. And yet, I get lots of stuff done. Just look at my bookshelf.

AA: Yeah. I mean, it just it sounds like you’ve just got this kind of holistic approach where everything you do somewhat keeps you moving forward to where you want to be. It sounds very nice. But it’s interesting to me, and it leads us on to my next question because clearly, friendship is pretty important to you.

GW: It’s vital.

AA: And I’m assuming a lot of your friends do come from the sword world, although not all of them. So it made me wonder what the what if there is such a thing as the sword fighting community, and if so, what sort of people tend to gravitate towards it? If you can sort of describe who they tend to be? I’m assuming men a lot of the time.

GW: Fundamentally, the sword world is made up of people who are mad about swords. And there is no other demographic distinction.

AA: Really? Oh that’s great.

GW: Really. They can be from any culture, from any background, from any profession, you know, pick your demographic point. I know one of my students is a woman in her mid 60s who started swords last year in America. And I recently interviewed a woman in Jakarta who’s Muslim and in her 40s and who started swords of in her 40s and I have students who are young white men from wherever and computer programmers, historians and lorry drivers and airline pilots and think of a profession and you’ll probably find somebody in that profession who like swords, I mean, BDSM models also like swords. At least, some of them do. So there is no there is no distinguishing factor. But, the field was founded by and large 30 odd years ago by people like me. We tended to be young white men.

AA: With martial arts backgrounds?

GW: Not necessarily, but at university with a sufficiently, shall we say, supportive environment that university was an option. And so what we tend to see now, 30 years later, is many of the best known figures in the field, because we’ve been in it the longest are middle aged, usually bald, white dudes with university backgrounds. And that is a very, very small demographic. But representation matters so it attracts itself. So we tend to get lots of young men. But there are an abundance of women who are madly in swords.

AA: I’m very happy to hear that. And of course, I know, as you’ve said to me before that you don’t feel like you’ve got to where you want it to be in terms of representation, but it’s clearly on its way. Even though the people at the top of it, if you just looked at them, you might not be aware of how far it’s come.

GW: There’s always going to be that kind of founder glow around some of us. Which is bullshit because it’s just this halo effect entirely. But there are now, because this has been going on long enough, we now have people who have a decade plus of experience and who are highly respected instructors in their own right who are not middle aged straight white dudes.

AA: So this will begin to change the culture.

GW: It has been changing for a while. Yeah, actually, I had a problem recently. You know, this podcast has an absolutely strict slightly more than half of the guests must be female. I realised I need to go to interview a few men because I had too many women lined up.

AA: I’m just delighted and fascinated, honestly, that you found enough women. Because I wouldn’t have expected that because of my experience in sword fights, in stage fight 20 years ago. I really wouldn’t have expected that. And it was a nice surprise to hear that from you.

GW: 20 years ago, it wouldn’t have been. It has gotten a lot better. And yeah, we’ve got historical martial arts clubs in well, like Jakarta. I just interviewed someone in Jakarta and in all sorts of other places in the world, in South America and Southeast Asia. There must be some historical martial arts clubs in Africa, but I haven’t looked hard enough yet. So far in the podcast, we’ve got all the continents except Africa properly represented. We have African martial arts on the podcast. But I haven’t actually interviewed someone who is running a historical martial arts club in Africa. So if you are listening to this in Africa, and you are involved in historical martial arts. Get in touch. I’d like to get you on the show, so we kind of get all the continents represented.

AA: I was wondering when I was preparing to ask you this question, I was wondering, are you going to say most of the people are historians or are you going to say most of the people have a martial art background? And it sounds like neither of those things are the case.

GW: Yeah, you know, we don’t have like the proper studies, you know, sociological studies and demographic studies, to be really certain. I mean, some professions are probably overrepresented.

AA: Like what?

GW: In my experience, there’s a lot of computer programmers.

AA: Oh gosh, how interesting. In my world, which is being a photographic model, a lot of my photographers are amateur photographers. And most of them are I.T. consultants. It’s not what I expected, but that’s the case. It’s fascinating, isn’t it? And makes you wonder why.

GW: I think because they get paid well and they so they have time and money for hobbies.

AA: Yeah, that’s probably a fair point. And I think maybe in my experience, at least, I think that people who work as IT consultants, they’re often smart and they’re computer literate. But what they’re not getting to do is use their creativity necessarily much at work. And they need an outlet for it. And I wonder there’s something a little like that going on with all your computer programmers.

GW: Yeah, I think anyone in any kind of abstract profession needs something physical

AA: And non-physical profession, yeah.

GW: So they need something physical. I introduce the show with “Hello, sword people”, because that’s the demographic.

AA: That’s lovely.

GW: It’s people who like swords.

AA: And what it means is, I think anyone listening to this who is a sword person, but who’s never taken any steps to meeting other sword people in real life, going to any classes, I guess that means they don’t need to be afraid that they’re not going to walk into a sort of a club where everyone’s the same except for them, which is a nice thing to know.

GW: Although, you know, some clubs are like that. We do have a problem with some clubs who very deliberately only recruit certain demographics.

AA: Oh.

GW: In the same way that the Nazis borrowed a whole bunch of like Norse mythology and perverted into their own ends. It is a historical fact that one of the main uses of medieval martial arts skills, in, shall we say the 15th century, was to prevent Islamic incursions from the Ottoman Empire into Europe. And so there was a lot of fighting going on between, shall we say, Christendom and the Ottoman Empire. Crusades and things like that. So there’s this sort of, if you like, baked in Islamophobia into the original “Knights of Old” whose martial arts we are copying.

AA: I would not have thought of that. Yes, it makes sense.

GW: It is also true that the founder of Aikido, the sort of “way of peace” – I love Aikido, it’s one of my favourite martial arts of all – but by any reasonable standards, at various points in his life Morihei Ueshiba was a raging nationalist fascist. That’s indisputable.

AA: So what you’re basically telling me is that there are clubs like Miyagi Dojo in Karate Kid and there are clubs like Cobra Kai with the baddies in it.

GW: It’s not quite that black and white.

AA: It really is, I’m sure it is.

GW: It really isn’t quite that black and white. But there are certainly there are certainly clubs where if you are, I don’t know, not white and maybe trans, for instance you would be better off going to this club than that one.

AA: And I guess you can point people in the right direction if they are looking to get involved.

GW: As a general rule, if the person who is running the club or involved in the club has been on the podcast, chances are you’ll be all right.

AA: Right. Oh, well, that’s nice to know. So I hope anyone who’s listening, who’s thinking of taking that first step will kind of be reassured by that, because to be honest, I would be reassured by that because I doubt I’m going to get to go to any of these clubs because I’m too busy. But the idea is really appealing. But then I think, oh, what sort of people would I meet and would I be welcome? And it’s nice to hear that actually, that might not be an issue because if it isn’t an issue me, it probably won’t be for other people. All right. So this is my penultimate question. We began to touch on this already in your last answer. But so I feel like it would be fair to describe you as a feminist. Would you describe yourself as a feminist?

GW: I mean, yes, obviously. But there are a million different kinds of feminist.

AA: Yes, there are.

GW: I generally avoid labels where possible.

AA: That’s understandable.

GW: On the one hand, at the moment, the pendulum is still very firmly biased in the direction of patriarchy and male supremacy. The world is built for men. Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez, that’s why I started the podcast as basically a response to that book. So I think that’s true. And I think it is necessary to get the pendulum where it belongs, it is necessary to push it a bit further in the opposite direction.

AA: Yes, until it hopefully eventually settles in the middle.

GW: Until it settles in a more equitable thing, which is why you need things like affirmative actions of various kinds. But at the same time. I’m not in any way anti-male.

AA: God, no, no, me neither. I mean, I describe myself as a feminist, but it’s not because I don’t like men at all, at all.

GW: You married one. I assume you like him quite a lot.

AA: Yes. It’s just you’ve clearly mentioned multiple times through our conversations the sort of feeling of responsibility trying to sort of redress the balance in a traditionally male dominated field.

GW: Yeah.

AA: So what my question was really and you partially answered it. What does it involve for you, the trying to redress that balance, so obviously representation of women.

GW: I mean, the main thing that I’m doing now on this front is the podcast. But it’s not all women. It’s simply at least half of the guests are women.

AA: And before you mentioned demonstrating stuff in classes with women, which was an interesting one that hadn’t occurred to me.

GW: The person the martial arts instructor demonstrates with is literally set up as an example to the other students. And it’s helpful for people to see people like themselves in that position. It basically shows them that it is possible for them. That’s the thing. Honestly, probably the most useful thing is, wherever possible, I just shut up.

AA: Oh, that sounds quite sad.

GW: No, it’s not, it’s not. It’s not sad at all. I get plenty of chances to talk. I am not in any way repressed or downtrodden or whatever. I mean, I talk a lot on this podcast. You may have noticed and I have my books and my courses and my students.

AA: Your voice is heard a lot.

GW: And in any historical martial arts setting, whatever, my voice carries more weight than it probably should because halo effect and time rather than lack of stuff, right?

AA: Maybe. I mean, I feel like you’ve earned that position. It’s sort of being aware, I guess aware of the power and loudness of your voice.

GW: Yeah. So I generally don’t weigh in on when women say stuff about patriarchal bullshit and what have you, I just keep my mouth shut. Because as soon as I start to talk, it’s some bloke sticking his nose in, where it really is not needed.

AA: I believe one of the powerful things you’re doing is something you’re not doing in that regard.

GW: Actions like having a podcast with a gender quota is hopefully a useful thing. And if you want to see my politics, it’s probably better to look at what I actually do rather than what I say, because all sorts of people will say all sorts of shit and do nothing. I’ve never joined a political party before in my life. But last year again, thanks to Caroline Criado Perez, I joined the Women’s Equality Party. I am a paid up member of the Women’s Equality Party of Great Britain. Doesn’t mean I’m particularly active in anything.

AA: But it’s a thing you could actually do.

GW: Right. Because it’s a low hanging fruit. It’s by no means the whole tree, but it’s a low hanging fruit. Women are about half the population. Get that imbalance redressed and I think all sorts of other imbalances will naturally be redressed in the same process, or we have a much more solid platform from which to address them.

GW: But just makes sense to me to address the low hanging fruit first.

AA: So the short answer to my question is really you’re doing plenty, like that’s what you’re doing. You’re doing plenty of stuff. So on behalf of women, thank you.

GW: Very nice. Well, you’re welcome. It’s really not very much. But there we go.

AA: Well, but because of the field you’re in, actually I think it’s quite a lot. That’s my personal opinion, that it means more when you’re in a field where women have been quite underrepresented. But obviously taking complements is horrific, so we’ll move on.

GW: I’m just being quiet and letting the woman do the talking.

AA: OK, so this is my last question, and I’m very interested in this because when you interviewed me, I talked about how my stage fight training, for a while especially, gave me this ridiculous, false confidence that I could probably fight anyone. And I’m embarrassed admitting to it, especially when you said that you were avoid fights at basically all costs, even though you’re far better qualified than me to get into them. So I found myself after my interview with you, I found myself wondering what the real world applications are that you’ve found for your knowledge and training? In what ways do you think this has changed you as a person?

GW: OK. Fundamentally, I see all problems in swordsmanship terms.

AA: Tell me about what that means.